By September 1815 Thomas Bond was in Stafford gaol – one of 10,000 people imprisoned for debt each year during the 18th and 19th centuries. Life in the debtors’ prisons of the early 19th century could be harsh; a prisoner had to provide his own food, clothes, and water, for example, so without a supportive family, even survival was difficult. They were also dirty and around 25% of the inmates died due to the unsanitary living conditions. There was no term limit on imprisonment for debt; release was determined by the creditors. Records so far found do not show how long Thomas was in prison. The next documented evidence for his debt problem is from January 1817 and it is possible that he remained in gaol until then.

Some debtors’ prisons allowed the debtors to conduct business and receive visitors even in locations outside the gaol. Family visits were also possible. From the information available it is quite possible that Thomas was in fact released from gaol earlier than the January 1817 document suggests and back in Armitage working as a brickmaker and maltster and running his farm (which was at the old Hawkesyard). His fourth child, Jonah, was born on 3rd August 1817 and baptised at St. John the Baptist church on 7th August with Thomas’ occupation given as maltster.

In April he was looking to buy two more canal barges in addition to the one he already operated.

In September 1816, he took out fire insurance with the Union Fire Insurance Society for:

- £600 on two dwelling houses constructed of brick and tile, stables, malthouses and storerooms adjoining each other in the occupation of Thomas Bond and Revd. Daniel Morgan

- £600 in stock of malt and other grain in the aforesaid malthouses and storerooms

- £150 on household furniture, plates, linens/dressing apparel, printed books and dairy and brewing utensils in his said dwelling houses

- £300 on beehives and live and dead farming stock on his farm and in his farming buildings at Armitage

- £70 on a barn and granary adjoining near built of brick and tile

- £30 on a brick and tile stable near the above

- £40 on a thatched shed for the purpose of drying bricks

- £50 on a brick and tile dwelling house at the Beatings in Lichfield in the occupation of Joseph Shaw, brickmaker

- £70 on a thatched shed at the Beatings for drying bricks

The insurance discussion was taking place in the summer of 1816, but the final document was signed on 24th December 1816 with Thomas described as brickmaker, maltster and farmer. But not as a potter.

In the Armitage Brickworks documents at Stafford Record Office series D603/X/6 are eight files. Six of them are books, one is a couple of loose supplier invoices, and the final one is simply “loose papers”. In these loose papers are a wide range of documents like the fire certificate, invoices, production records etc.

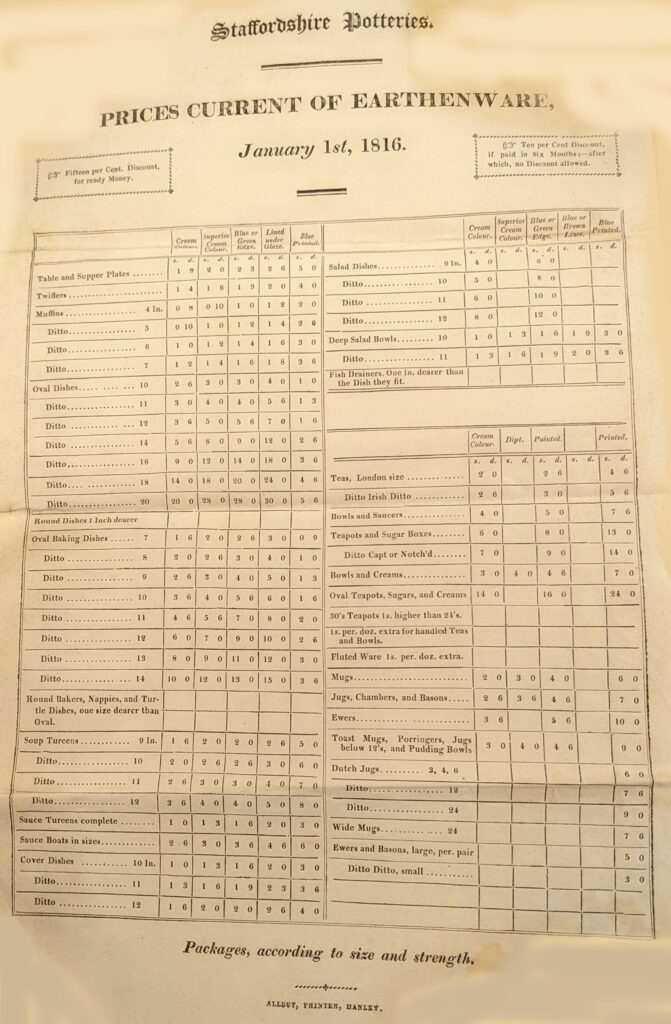

Included also is a price list for earthenware, shown below, dated 1st January 1816, for Staffordshire Potteries. A website dedicated to the history of potteries. Thepotteries.org, has the earliest reference to a business named Staffordshire Potteries is from the 1850’s and in London. Given that this document is in Thomas Bond’s file it must be connected to Thomas and the likely reason is that it was the name of his failed Burslem venture and potentially the name of his Armitage venture.

From all the evidence so far found, Thomas was not working as a potter in 1816. In January 1817 his creditors were summoned to a meeting to assess his financial state and presumably they were satisfied. He immediately rented from John Alldritt the pottery in Armitage next door to his house. Like with the malt kiln he may have been sharing the pottery premises with Thomas Alldritt and Thomas Smith who were themselves partners in a pottery business.

An article in the Staffordshire Sentinel in July 1880 stated, “In 1817, an adventurous soul named Alldrett, and another named Smith, both of them brewers, mingled their brewing of potations with the manufacture of pots to drink them in”. Disparagingly it went on to say that “what these potters attempted to do was little more than yellow ware”.

Yellow ware is low cost and durable and the yellow colour that comes from the clay mix is generally just covered with a clear glaze.Alldritt and Smith may have done some brewing but that was probably just for their own consumption; it was certainly not a very important part of their business, so they were not just making pots for their brewing customers.

Thomas Bond intended to make creamware, so he had plenty of work to do and he needed a lot of money. Whilst he didn’t neglect his brickmaking and malting business he needed to concentrate his efforts on the pottery. As an example, in June 1817, he agreed a deal to sell the Earl Talbot 200,000 bricks and deliver them in good condition to Weston at the rate of 33 shillings per thousand bricks. He would deliver two boat loads every week until the order was fulfilled, and he would be paid by draft two months after delivery of each load. This meant that he had not only secured good funding but would have to spend less time on the sales side of the brickmaking business.

The people who would make the ware, most if not all from the Potteries, supplied their labour and skill. In return, Thomas’ role was to provide a place to work, equipment, raw materials, and payment for the ware produced. Storage of the completed products would be needed together with selling and delivering the ware and, of course, collecting the money owed.

Very briefly, pottery is made from a mix of clays, flint, stone (often Cornish Stone), all of which have to be in powdered form, and water which are all blended together to make a thin slurry which is called a slip. This was then heated to remove water until it became a soft putty like consistency and this malleable material is then used to form the shape of the ware. At this point it may be further worked on to add decorations, handles, spouts etc before it is dried in the ‘hot room’. Once the ware is dried it is heated to about 1200°C in a kiln (biscuit kiln) to make a porous piece of ware called biscuit ware. After decorating the biscuit ware with a glaze, the ware is placed in another kiln (glost kiln) where it is again heated to above 1000°C to produce the glazed waterproof ware.

From April 1817 William Conway, a blacksmith in Handsacre, began supplying Thomas Bond and his invoices over the next twelve months shed light on the rebuilding and expanding of the pottery. The first six months or so show repair and minor work e.g. new hooks and catches for the oven doors, repair of potters’ lathes, fixing a strong metal plate to a plank for slip making.

By August Conway started making new iron frames, bands, brackets and doors for the pot oven and in November he began supplying king pieces for new buildings including warehouses and the sliphouse. Taking advantage of the heat used in the malt kiln Thomas built the sliphouse over the malt house together with a new warehouse.

This part of the land therefore had two houses, one of which contained a chapel, a small brewery, a drying kiln (for malt), the malt kiln, five small rooms, the slip house, a coal house, a wash house and a pigeon room.

In the pottery next door, near to the two ovens he erected six double storey buildings with a room/warehouse on the top floor and dip house, turning house, handling house (for fixing handles on to the ware), hot house, throwing house and a clay house on the ground floor.

In yet another separate area, a saggar house stood next to a barn, two stables, a cowshed big enough for eight cows and three piggeries. This was the start of manufacturing in Armitage and clearly there was no planning control!

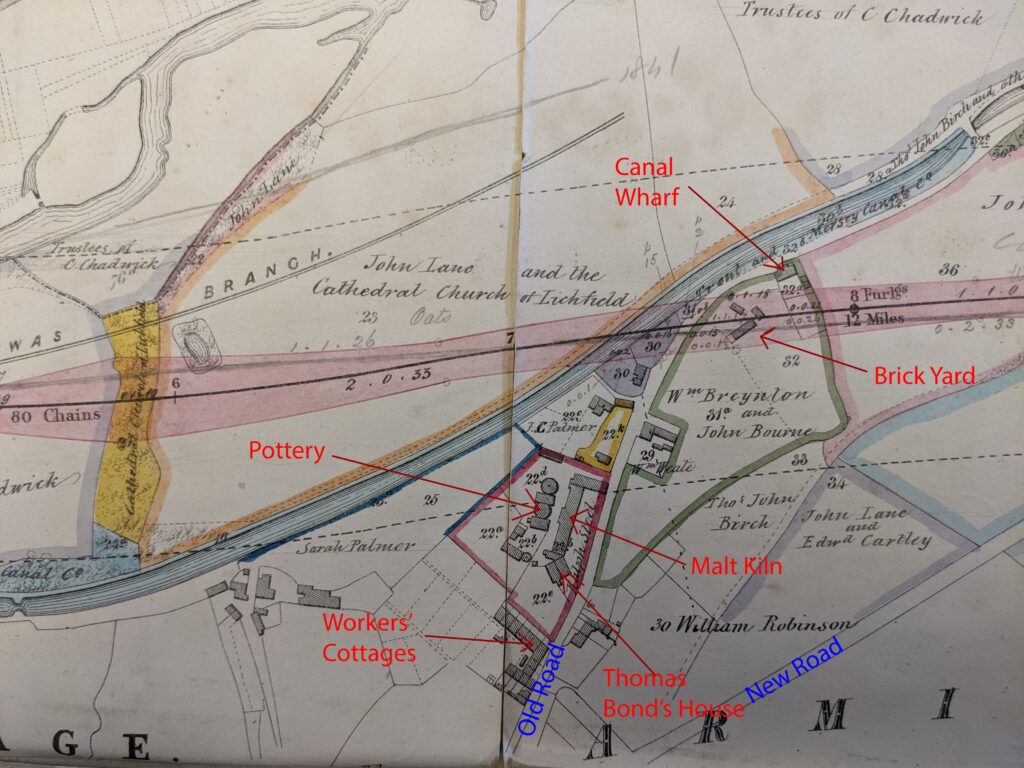

Towards the end of the year Thomas decided that he also needed to supply workers’ houses to entice sufficient skilled potters from the Potteries and nine workers’ cottages were built each with its own garden. The general layout of the brickyard, malt kiln and the pottery is shown below.

On 1st October 1817 Thomas Alldritt and Thomas Smith, maltsters, brickmakers, corn dealers and potters, ended their partnership. As a result, Thomas Bond was able to buy Ball Clay from Thomas Alldritt at a good price. As they had been sharing the malt kiln and pottery with Thomas Bond, he was now free to develop it as he saw fit. He borrowed £4,000 from John Haynes of Crewe Hall and bought both the malt kiln and pottery, together with the two houses, from John Alldritt.

Whilst all this layout and building work went on Thomas was also busy making sure that he sourced all the necessary raw materials and ancillary equipment he needed. The clays were easy to source and did not need any processing before mixing but stone and flint both had to be crushed and powdered.

The flint was bought from Thomas Marsh, a customer of the malting side of the business, who ran Colton Mill (which was where Brooklands Trading Estate is now at Rugeley Trent Valley). As the mill had the capacity to crush stone, they may also have provided that as well. Payment for the crushed flint was by a mixture of cash and malt.

In an article in Waterways World, Tom Foxon described how the flint was transported from a wharf at Brindley Bank to the mill. Flints were taken from canal boats at the wharf and transhipped onto river craft for the 1100-yard journey to the mill. From the canal they were barrowed along a plank supported by two wooden piles and a crossbar. A block of wood at the end of the plank would have prevented the barrow from slipping off the end of the plank while the flints were being tipped into the barge. Loaded boats would have been helped by the flow of the river to the mill whereas the return journey in the square-rigged craft would be assisted by the prevailing southwest wind.

Stone was also sourced locally. Records for the carters and labourers show ‘one day drawing stone’, ‘one day at stone quarry’, or ‘one day at new stone quarry’. There are no records to show where the quarry was, but it was presumably local and may have been the one shown on OS maps near Armitage Lane, Brereton. William Conway’s invoices frequently show him charging for sharpening dozens of stone picks and chisels and for 20 new holdfasts for stones – used to hold stone in place whilst it was processed.

Thomas bought ground iron stone from George Ryles of Burslem together with moulds for ewers and basins and 14 engraved copper plates for decorating his ware. Ryles was another malt customer, and he too was paid in a mix of cash and malt.

Once all the building work had been completed and the necessary materials obtained, the pottery business began in earnest, but the malting and brickmaking still had to carry on. D603/X/6/7 shows the daily pottery production but if the shared labourers actually worked at the pottery for the day their time was recorded as ‘at the Bank’.

For w/c 27th July 1818 the production sheet (for a 6-day week) shows: –

- Chris Ball (carter) – 3 days hoeing potatoes, 1 trip to Walton collecting straw, 1 day taking bricks to Cartwright, 1 day hauling bricks and jobbing

- Jeffkote (carter) – 3 days hoeing potatoes, 1 day on kiln, 1 day in warehouse

- Matt Shipley (carter) – 4 days ploughing at Hawkeshwead, 1 day drawing timber, 1 day to coal pit

- Thos Hughes (carter) – 2 days to coal pit, 1 day harrowing Hawkeshwead and jobbing, 1 day drawing bricks and to coal pit, ¾ day drawing wood, 1 day drawing bricks and to coal pit

- D. Jackson (labourer) – with Shipley

In the same week the pottery employed slip makers, stilt makers, handlers, squeezers, packers, painters, saggar makers, crate makers, warehousemen and women, one thrower, five turners and a dish maker. Each of these last three jobs also needed lathe turners.

James Birks was the only thrower employed that week. The records show that he produced the list below, and it signified a dozen of each item i.e. 20 dozen egg cups: –

- Flour pots x 40

- Basins x 110

- Chamber pots x 160

- Bowls 24” x 100

- Bowls 12” x 100

- Pepper pots x 20

- Mustard pots x 20

- Egg cups x 20

- Mugs x 72

- Ewers x 40

These items are on the list of Staffordshire Pottery (shown above) but the pottery produced a wider range of products e.g. wine coolers, urns and even basic garden pots

The final part of Thomas’ role in running the pottery business was to find buyers for the ware, get the ware delivered and collect in the money. Telling customers what they could buy and at what price was obviously key and he knew potential customers from his time in the Potteries – he may well have used the Staffordshire Potteries list (shown above). A factory showroom was often used for showing the ware but Armitage was miles from the Potteries and customers would not want to make such a trek for one small pottery. Thomas instead rented No 21 Wharf at Paddington on the Grand Union Canal and installed his own man there – John Ellis. This gave him both a stock of goods near plenty of customers but also a place where potential customers could visit. He could use his own canal boats for deliveries but for the main route to London he normally used one of the bigger carriers like Rutty & Sergeant who had their own wharves at Paddington.

There are examples of orders with a wide variety of dinner service items but a fairly standard order would be the following example for a Mr. Jacob Phillips, Oxford St., London: –

22½ dozen chamber pots @ 2/- £2 – 5 – 0

9 bowls 30” @ 2/- £0 -18 – 0

Crate & straw £0 – 8 – 0

Carriage to Paddington £0 -12- 0

Total £4 – 3 – 0

Towards the end of 1818 he was in discussion with his cousin, John Phillips, about Phillips taking a bigger role in the sales side of Thomas’ business. Phillips stated that he would need to be supplied with 3 or 4 Hawkers Licences if he was to make it work. In December 1818 Thomas received a letter from Sgt. Major John Hunter who was currently serving with the 57th Foot at Chatham:-

Sir, I received your kind message from the hands of Mr. Philips, and feel grateful for the interest you take in my welfare, but as I know not what the duties of the situation you mention may be, I cannot form any idea respecting the salary, therefore if you will have the goodness to write by return of Post, and inform me of the particulars, and likewise what salary you intend to give, I will be happy to engage with you, if I find it equal to the support of my family.

You will at once perceive the necessity of my being this explicit as to terms, when you consider the unavoidable expense I shall incur in travelling through the Country with a wife and four children.

Your early acknowledgement of this will greatly oblige.

There is no further record to indicate that Thomas employed Sgt. Major Hunter or similar individuals.

Making and selling bricks and malt was straightforward compared to selling a wide range of pottery and Thomas needed employees to do more record keeping. His employee based at the wharf at Paddington, John Ellis, left the business in early 1819 without telling anyone that he was going – Thomas stated that he absconded – and the wharf was left unattended. Another of his warehouse men sent crates of ware to a different wharf in London without recording either the contents or the destination. Thomas also had problems making sure that third parties kept to their agreements. Rutty & Sergeant overcharged him for transporting his ware and when he refused to pay the extra amount they kept his ware. These issues wouldn’t have helped Thomas develop his business and before long he ran out of money.

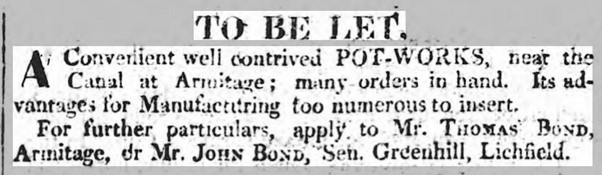

On 25th March 1819 the pottery produced its last piece of ware. The following advert appeared in the Aris’s Birmingham Gazette in April 1819.

Thomas had already been to gaol for being an insolvent debtor and he had no wish to repeat that. Insolvency is a financial state where a person cannot meet debt payments on time whereas bankruptcy is a legal process that happens when the individual declares they can no longer pay back their creditors. Once you are bankrupt your creditors can no longer demand payment from you or charge interest or take further legal action against you. Any assets you have will be put to paying off your debts but at the end of the bankruptcy process any outstanding debt would be written off giving you a fresh start.

The problem for Thomas was that to qualify for bankruptcy in 1819 you were supposed to be a trader, making your living by buying and selling. Strictly speaking Thomas didn’t qualify. If he described his occupation slightly differently though he would qualify and, like a good many people in his position at the time, he added two new occupations. As well as brickmaker, maltster and potter he now described himself as a trader and chapman. (A chapman was an itinerant dealer). The bankruptcy process duly began.

His creditors first had to petition the Lord Chancellor who issued a Commission of Bankruptcy. This was published in the London Gazette and in all the national and local newspapers. The dates, times and locations for three public hearings were declared – 5pm on 18th June and 11 am on 19th June, both at the Crown Inn, Rugeley and 12am on 17th July at the Talbot Inn, Brereton.

The London Gazette also showed, a few lines down from Thomas’ bankruptcy hearing a bankruptcy hearing for John Bond of Lichfield, maltster and brickmaker with the same locations and dates for the hearing. Presumably Thomas and John were in partnership, and both were made bankrupt. But which John Bond – Thomas’ father or Thomas’ brother? Normally if it was his father, you would expect him to be shown as John Bond Snr but then again the address given was Lichfield and occupation as maltster and brickmaker which suggests that it was indeed Thomas’ father.

The hearing had a number of purposes. Firstly, Thomas had to ‘surrender’ himself and provide details of all his effects and financial dealings. Secondly his creditors had to bring evidence to prove what they were owed. As the debts could not all be paid assignees were appointed whose job it was to deal with Thomas’ estate to release the assets and ensure the creditors were paid as much as possible.

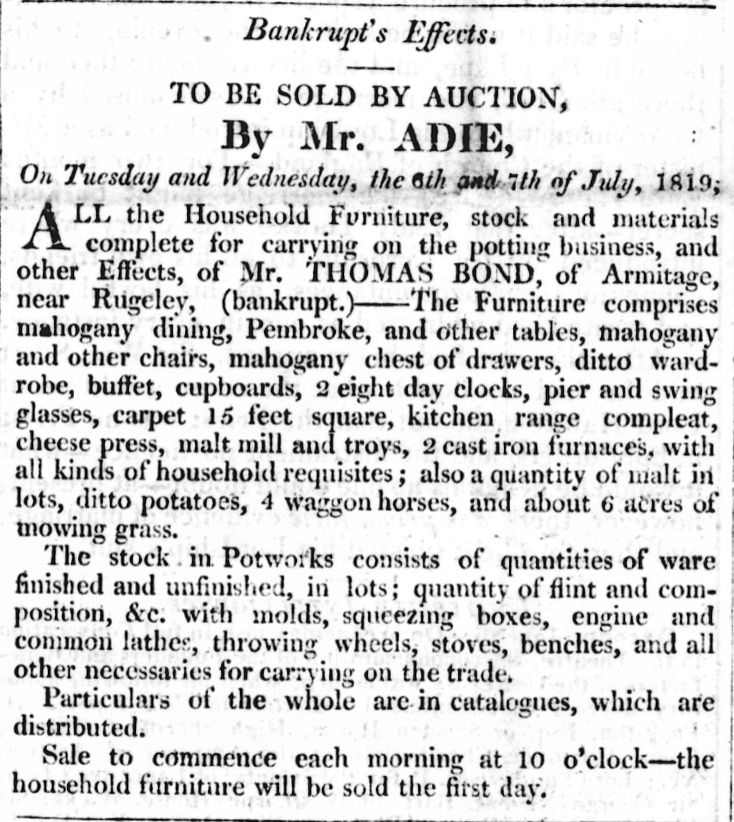

Even before the third meeting had taken place the assignees had put Thomas’ effects up for auction as the clipping below from the Staffordshire Advertiser on 3rd July 1819 shows. All the portable manufacturing equipment was listed. Household furniture was also listed but for some reason this did not include any beds – maybe they had been sold separately. Stocks of bricks were easy to sell and didn’t need auctioning off to get the value.

Fixed equipment like the bottle kilns, the workers’ cottages, malt kiln and brick drying sheds were now owned by the person who owned the land on which they were built. Apart from the brickyard all the land was taken by John Haynes who had loaned the £4000 to Thomas.

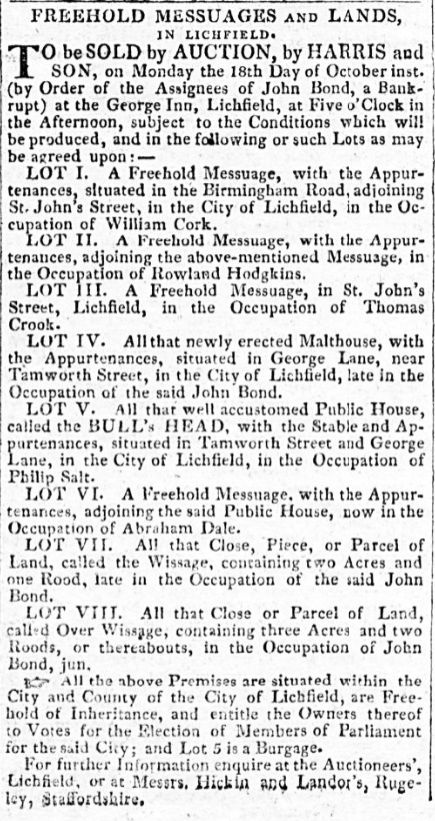

Things went from bad to worse for the Bond family as this clipping from the Aris’s Birmingham Gazette shows in October 1819. This confirms that it was Thomas’ father who was either in partnership with him or was acting as his guarantor and all his property was also forfeit.

The assignees called all Thomas’ creditors to a meeting to be held on 28th November at Attorney Salt’s office in Rugeley. At this meeting the creditors agreed that Thomas’ estate had been liquidated and that all monies owed had been collected. The London Gazette issued a statement saying that ‘the said Thomas Bond hath in all things conformed himself according to the direction of several Acts of Parliament made concerning bankrupts’ and his Certificate (i.e. discharge from bankruptcy) will be allowed and confirmed on 2nd December 1819. His father’s affairs were more complicated, and he was not granted his certificate until 26th June 1820.

Thomas was now able to start again.