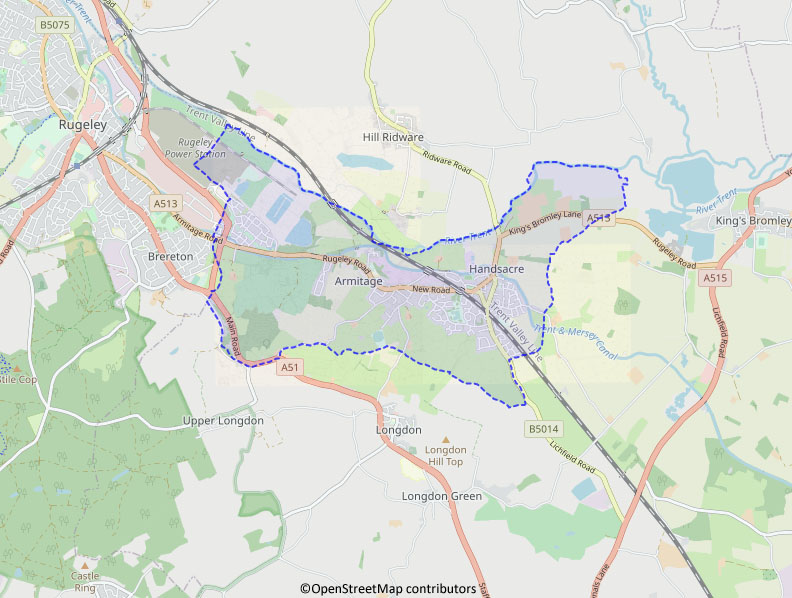

The village of Handsacre lies in the centre of the East ‘wing’ and was the focal point until about the 15th C and the original Parish borders were in fact those of the Manor of Handsacre. Just South of the river above Handsacre there are numerous field markings which can best be seen from the air and when there has been a drought and they have been identified (but not excavated) as both late Neolithic and Bronze Age (2100BC to 750BC in the UK). Most of the markings are round barrows with two concentric ditches, varying from 7m to over 30m in diameter. In the 19th C at least they were in what was termed ‘the Barrow Lands’.

In the same area we have a trackway, rectlinear enclosures up to 100 m across and a long mysterious series of pits – 2 to 3 m dia. – stretching in a regular line over several hundred metres, all from the Iron Age period. Three miles South West of the Parish is Castle Ring – you can just see it on the map above – which is 500 feet higher and the highest point on Cannock Chase. It is one of seven known hillforts in Staffordshire and believed to have been in use from about 500 BC to the time of the Roman invasion. It was built by the Cornovii whose heartland was in the Wrekin area and was built to overlook the border with the Coritani tribe who were centred in Leicestershire so the River Trent was quite possibly the border between the two tribes.

The Romans had a camp at nearby Wall but the only current evidence that they passed through is the find of two Roman arrowheads (or possibly ballista bolt heads) and two spear heads. They were found in 1782 at a depth of about two feet in Mr. Moor’s garden which is believed to be Ivy Cottage – this was opposite the Alms houses in Armitage.

Scholars don’t like using the term the Dark Ages (they prefer the Early Middle Ages) but it was originally used to denote a lack of written records and certainly there are none at all covering the Parish before the Domesday Book. By this time (1086) there was a village called Hadesacre and a ‘n’ was added shortly after but the spelling hadn’t settled down yet and it is variously written as Andesakyre, Hondesaker, Houndesacre, Hounzaker, Undesacre etc. It is now believed that the term ‘acre’ in the name refers to cultivated land on the edge of marsh rather than a specific area of land. Certainly the Hall was situated on a low hill jutting into what was the marshy area of the River Trent, (hence the name of Marsh Barns farm). Dredging of the river and building up of the banks following subsidence from coal mining have now disguised its previous meandering course and channelled it into only one, high-banked, course.

The Domesday Book, in the section referring to land owned by the Bishop of Chester, states ‘Hadesacre. The arable land is five carucates. Robert [of Stafford] holds it.’ A carucate is a term for the amount of land that a team of eight oxen could plough in a single season and is nominally equated to 120 acres. The arable land for the Parish was therefore about 600 acres whilst the total land covered by the manor was about 2000 acres. The rest of the manor was either marshy or considered waste for one reason or another. The manor was under control of Robert and most of the arable land would have been open fields close to the Hall – confirmation of this to some extent comes from the tithe map of 1841 which shows West Field ending at Hood Lane i.e. at about the midpoint of the manor.

The manor would have been centred on the main building which at that point may not have been grand but it was rebuilt a number of times and in about 1310 an aisled hall was built. The Hall was moated and faced North looking across the river. According to Stebbing Shaw (1798) the moat was five feet deep and had a draw-bridge with the area within the moat measuring 60 yards East to West and 54 yards North to South.

About 200 yards North of the Hall Stebbing found the foundations of a building measuring 18 yards long by 10 yards wide pointing East to West. Also found were scattered fragments of coloured glass and narrow lead strips and there can be little doubt that this was a church used by the Lord and his people. Written records survive in a court case showing that this was the church of St. Mary Magdelene. When Stebbing visited Handsacre the remains of a mill could still be seen approximately 200 yards North West of the Hall.

The first written evidence of the existence of a hermitage in the Western part of the Manor can be found in 1280 – a grant of five selions (strips of land) in Longedon to Johnes Capett of Colton and the hermitage of Hondeshakere. This reference also indicates that ‘the hermitage’ was now considered an area which, in turn, suggests it had been present for a considerable time . One historian gives the date of the Hermit as 1150 which sounds reasonable. The site of the hermitage, at some point, became the church of St. John the Baptist but there are no records showing its construction. In the early 13th Century the Pope required that all churches should have their own vicar and many churches became independent of the manor at that point so this supports the idea that the church dates from the early 1200s. (The church has been completely rebuilt over the centuries so there are no other clues). Neither are there any records to show when this church superseded the one built just North of the Hall.

In 1307 Sir William de Handesacre granted some land in his ‘waste’ to Richard, son of Henry de Heyham, and this deed was witnessed by his steward, Adam de Ruggeley. In 1337 the Ruggeley family were granted Royal permission to enclose 100 acres in the North West corner of the manor – le Haukeserd in Hondesacre, as a sub-manor of Handsacre . The foundations, plan and gardens of Hawkesyard were still visible when Stebbing Shaw visited in 1798 and they showed a 12 yard wide moat surrounding a square area 34 yards per side. It was quite close to the river and the area was quite marshy. The family had retained it until Sir Simon Ruggley first mortgaged and then sold it to Sir Richard Skeffington after the Civil War. It was formally disparked in 1665.

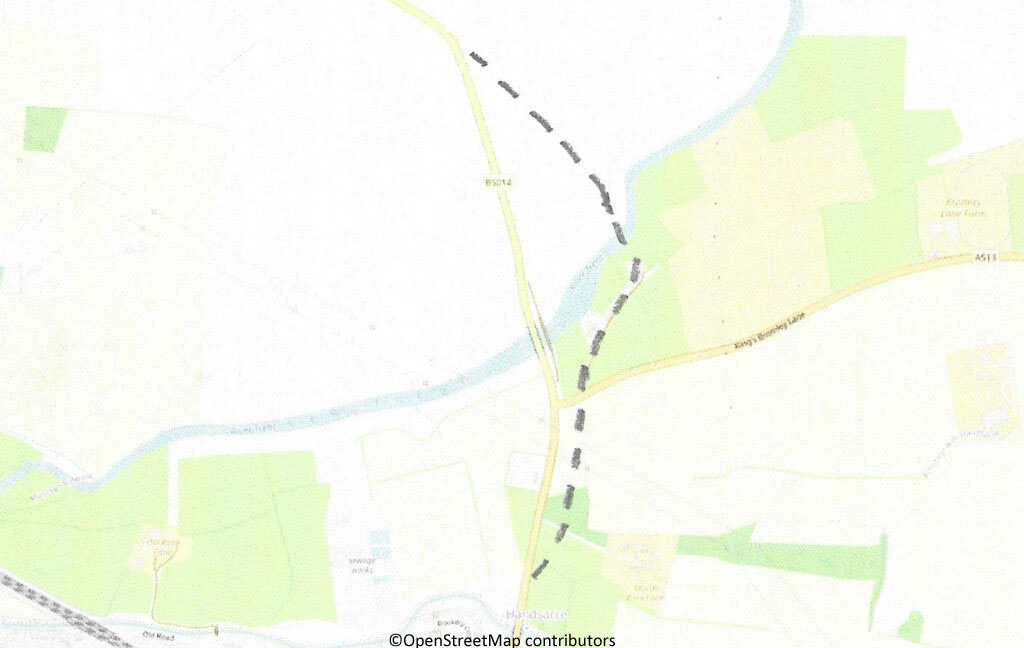

The bridge over the River Trent between Handsacre and Hill Ridware is about 25 yards West of the previous road bridge which itself is 200-250 yards West of the site of the first bridge and indeed the site of the ford that preceded the bridge. The ford crossed the river via a number of islands and the first bridge did the same but using a bridge with numerous arches with the whole structure made of timber. In 1322 the bridges were destroyed by the forces of the Earls of Lancaster and Hereford in their revolt against Edward II.

The current bridge over the River Trent between Handsacre and Hill Ridware is about 250 yards West of the original which is shown by the dotted line on this map. It crossed the river via a number of small islands with numerous arches – originally all in timber – and followed the line of the original ford. The Northern Parish boundary runs down the middle of the river and at the bridge the Parishes of Armitage-with-Handsacre, Mavesyn Ridware and Pipe Ridware met. In 1322 the bridges were destroyed by the forces of the Earls of Lancaster and Hereford in their revolt against Edward II. A booklet titled The High Bridges: Crossing the River Trent between Handsacre and Ridware is available from the Ridware History Society.

Neighbouring Mavesyn Ridware was ruled by the Malvoisin family and border disputes between the two manors grew in the late 1300s, particularly over a mill in the river dividing the two parishes. The dispute came to a boiling point when Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, rebelled against Henry IV in 1403. Sir Robert Mavesyn supported the King and took his retinue towards Burton to meet him. At the same time Percy was mustering at Stafford and Sir William Handsacre prepared his retinue but rather than headed through Rugeley decided to cross into Mavesyn and the two parties clashed in a field near the bridge. Sir William was killed by Sir Robert who then fought for the King at the Battle of Shrewsbury where he himself was killed. Rather than sparking a more vicious feud between the two manors they were united when five years after the battle Sir William Handsacre’s son, also called William, married Sir Robert’s daughter, Margaret. This, at least, is the romanticised version of events which was essentially written by Charles Chadwick for Rev Stebbing Shaw’s ‘The history and antiquities of Staffordshire’, published in 1798. In fact the skirmish is completely fictitious – for a much more accurate, and gruesome, version the Ridware History Society have published a superb booklet entitled ‘Mavesyn v Ridware – the skirmish by the Trent’.

The younger Sir William Handsacre died in the 1428 and there the Handsacre name ceased in the manor as he was only survived by two daughters who became co-heirs – Johanna and Margaret. One of Johanna’s daughters married Nicholas Westcote and the Westcote family ran the Hall for the next 250 years or so.

At some point, possibly at the time of the Reformation in the 1530s, the Parish was named Armitage so clearly the Handsacre part of the manor had decreased in comparison to Hermitage which had transformed into Armitage. The first Parish Register is missing but we do have some Bishop’s Transcripts with the first entry dated 6th July 1623 – the burial of Sir Richard Ruggeley. The following account shows that his death was more formally recognised later that year.

“Mr. Richard Rugeley departed this mortal and transitory life on Saturday, at night, the 5th of July 1623, at his house at Hawkesyarde, whose funeral was worshipfully solemnised according to his degree, on Tuesday, the 23rd of September following, at the Parish Church called Armitage, in the said Countye of Stafforde, the cheife mourners being his sonne and heire, Mr. Simon Roughesley ; his assistants, Mr. Tirkell Roughesley, brother to the defunct, and Mr. Rowley Roughesley, his kinsman, the penon of his arms boren by Thomas Roughesley, his second sonne, his coat of armes by Samuel Thompson Windesor, Herauld, who marshalled the said funeral, and is testified to be true, by us, whose names are hereunder writte, the 24th September, anno. 1623.”

As the economy and population grew the need for better transport links increased and the first impact on the Parish came in the form of a turnpike – the road from Lichfield to just over the bridges on the river was taken over by a Turnpike Trust in 1729 and a tollgate was erected on the road just over the bridge next to the many arched bridges. The road from that point on towards Uttoxeter was not turnpiked until 1766 which coincidentally was the same year that the Trent & Mersey Canal Act was passed.

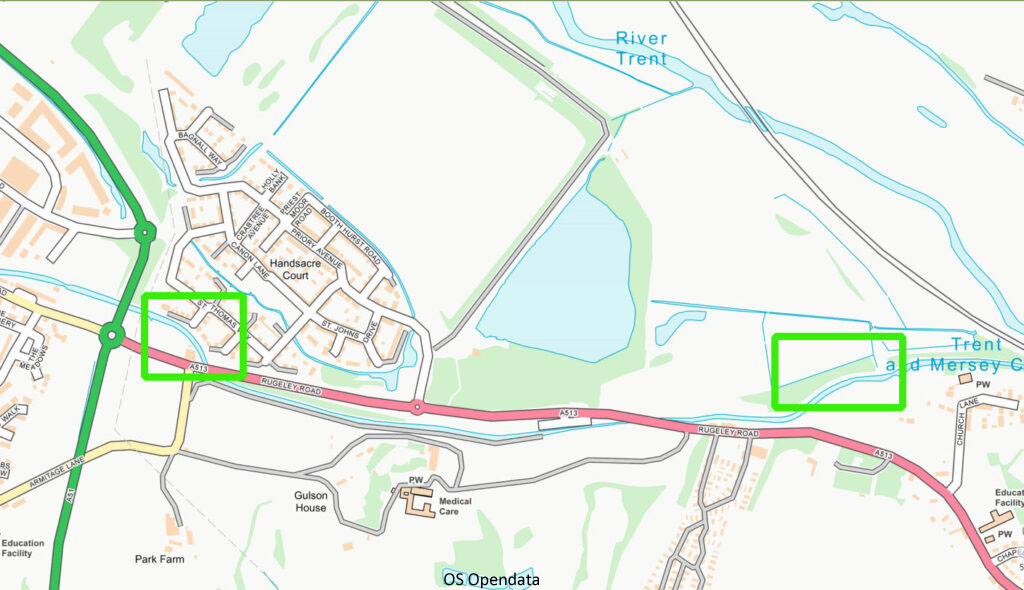

When building a canal the least cost option is to follow the contours and avoid any unnecessary work such as bridges and tunnels. When the canal was built through Armitage though, in 1770, the first canal tunnel in the UK with a towpath was built and from an engineering perspective there was absolutely no need for it – they should have built the canal in a straight line between the two green rectangles shown on this map. In 1760 Nathaniel Lister had built Armitage Park, now called Hawkesyard, and he didn’t want to see the canal when looking from his windows so he paid to have the canal brought closer to his house and therefore hidden behind a slight rise in his gardens.

John Alldritt and William Smith were maltsters and brickmakers in Armitage and, as a side line, they also had a pottery making drinking vessels. In 1809 Thomas Bond came to the village to work with them before going to the Potteries to operate a larger pottery manufactory. That venture failed as did his second which resulted in him being imprisoned as a bankrupt. Immediately on being released in 1817 he returned to Armitage, borrowed another £4,000, bought out Alldritt & Smith and set about rebuilding and enlarging the pottery and building houses for his workers. Over the course of the next two years the company employed over one hundred people at a time when the total population of the village was less than a thousand. In 1819 however Bond again became a bankrupt and the pottery was run by a number of different potters over the next ten years or so before closing in the late 1830s. A booklet entitled A History of Armitage Potbank Part 1 1809 – 1900 is available from the Ridware History Society.

The arrival of so many potters led to a number of houses being registered as Non Conformist places of worship including Thomas Bond’s own house but this photo shows the Congregationalists Chapel (now United Reform Church) built by Thomas Birch of Armitage Lodge in 1820. It had an ante-room, where his family could gather before the service, and a gallery, probably for use by the servants. The seven segments in the rose window are said to be unusual. In December 1831 he conveyed the Chapel to trustees so that it could be used as a place of public worship.

Another Turnpike Act in 1824, detailing a road between Rugeley and Alrewas, led to considerable change to the village between 1829 and 1832. A new road was built between Armitage and Handsacre and was of course called New Road with the original, winding, road becoming Old Road. The old bridges over the river would not be able to withstand increased traffic so a new, iron, bridge was built with a single span. This also straightened out the road between Handsacre and Hill Ridware and the old toll gate was demolished and a new one built, together with a new toll gate in Armitage at the junction of Old Road, New Road and Hood Lane. In fact Hood Lane became known as Pike Lane and the houses near the junction surrounded Gate Square (Toll Gate). The toll road also created Kings Bromley Lane – previously the route to Kings Bromley (and on to Alrewas) had been through Pipe Ridware, Hamstall Ridware and Morrey.

The Rev Francis Wilson was appointed to the Perpetual Curacy of Armitage in 1837 and he built Running Hills, later known as the Tower. He donated land at the top of Church Lane for a building of a National School which opened in 1840. He was responsible for the religious and moral training of the scholars with the first headmaster being Mr. William Wood. The school was enlarged in 1895 and remained in use as a school until 1939 whereon it became the ARP centre. After the 1939-45 war it was used for numerous village activities including as a youth centre and for scouts.

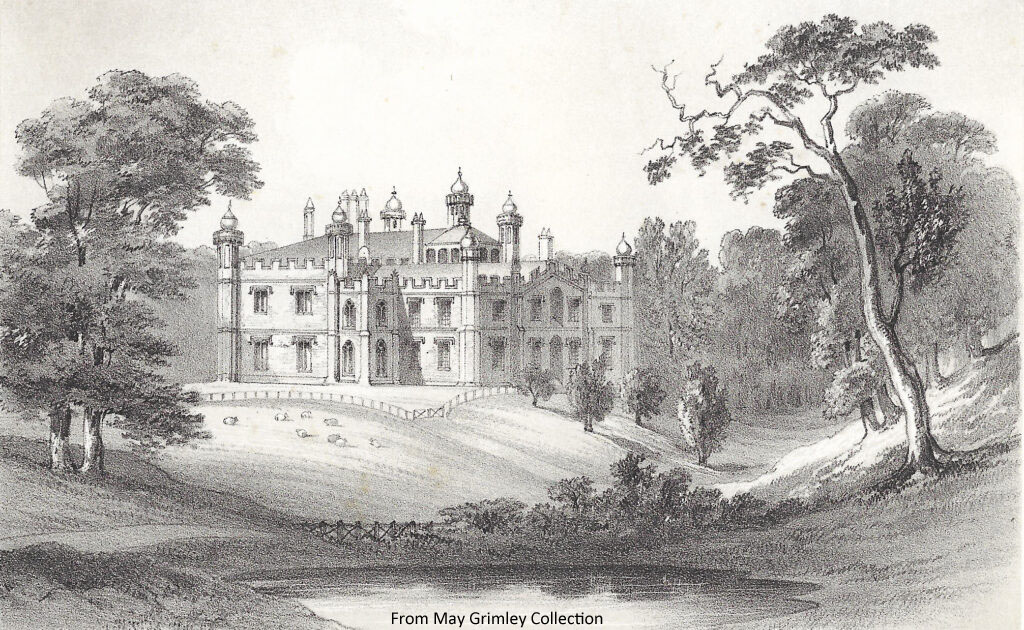

Mary Spode, widow of Josiah Spode III, bought Armitage Park in 1839 and lived there with her sixteen year old son, Josiah Spode IV and it became known as Spode House. The regular and well-proportioned hunting lodge was quickly modified with one of the wings being pulled down and rebuilt more grandiosely with more and higher-ceilinged rooms. Josiah Spode was a very keen organist and he donated an organ bought from Lichfield cathedral to the Parish Church where he became organist and choir master. He also had an organ loft built at Spode House and his mother built him a billiards room as a birthday present. In 1859 Josiah decided that the building should be renamed and called it Hawkesyard after the Ruggeley mansion just a few hundred yards away.

In 1845 the North Staffordshire Railway Company bought the Trent & Mersey Canal Company. There had been numerous proposals for railway routes linking Rugby and Stone and the Trent Valley Railway was finally built and opened in 1847. When the first train ran it was greeted by over 2,000 people at Rugeley Station which was the closest station until Armitage Station opened. The reduction in transport costs led, briefly, to the re-opening of the pottery by Thomas Salt from Burslem in 1852.

1852 also saw the construction of a second pottery by Robert Hedderwick Penman and his brother-in-law Thomas Carey Swann. Both were originally from Glasgow but had moved to London where Penman worked as a shipping agent and Swann as a printer. The pottery was of course called the New Pottery, although sometimes the Penman Works, and the original became the Old Pottery. As well as tableware they also introduced sanitary ware. In 1854 they had outgrown the site and considered expanding it but Thomas Salt went back to the Potteries in 1855 and they took over the lease of the Old Pottery as well. They had cash flow problems however and after a number of different partnerships Penman closed it all down and bought a pottery in Glasgow which initially he called Armitage Pottery. He closed that a few years later and emigrated to the USA.

The Old Pottery reopened in 1858 under George Salt and John Lloyd Mountford but it still struggled to survive. Over the next three years the pottery was run by four different sets of partners. The partners generally included people who were potters by trade e.g. Mountford, or people who had a business or commercial background. Thomas Salt – a potter by trade – came back to run the business sometime in 1861-2 but he lacked the business background and in 1864 the Rev Edward Johns came in and took over the pottery.

The Rev Edward Johns had been a roaming minister for the Primitive Methodists until marrying a rich widow about twice his age. He inherited her money and investments and set himself up as an auctioneer in Rugeley. In 1860 he joined the Rugeley Rangers (21st Staffordshire Rifle Volunteers) when it was formed by Josiah Spode IV and quickly became Sergeant. He won the inaugural shooting competition at Etching Hill receiving the Champions Cup. After one of his auctions at the Crown Inn in Handsacre he was approached by John Mountford about running the pottery. Although his second wife had just died giving birth to his third child he accepted the post, moved to live in Thomas Bond’s old house in Armitage, and quickly set about making the business profitable. In 1867 he persuaded Josiah Spode to buy the Penman Works, knock it down and loan him £1,000 so that he could buy the Old Pottery himself! He was the epitome of the Victorian middle class industrialist – charismatic, hard-working, religious and ruthless.

Edward Johns recognised that the sanitary trade was going to boom and he decided that the company would concentrate exclusively on products for that trade. The company bought in skilled potters from the Potteries and Scotland and he developed contacts with innovative designers. The pottery thrived and exported all over the world and reportedly was awarded with a medal at the Centenary Philadelphia exhibition (1876) with a novel water closet – the Dolphin. When he took over the company it had two kilns and everything was done by hand but powered equipment and the building of an extra six kilns greatly increased capacity. During his time the workforce increased from forty to over a hundred and he also found time to build a Club & Institute for the people of the village. When he died in 1893 the company was taken over by his son – Edward Lewis Williamson Johns.

Non-conformism flourished in the Parish with the support of the Birch, Johns and Morecroft families. A Wesleyan Chapel and a small Mission Hall were built at the top of Old Road. On 1st September 1879 Mrs Morecroft laid the foundation stone for the Zion Chapel (Primitive Methodist Connexion) which was converted into a house in 1892 and is now Handsacre Villa. The Primitive Methodist Temple in Handsacre was completed in 1894 with the foundation stone from the Zion Chapel included in the wall.

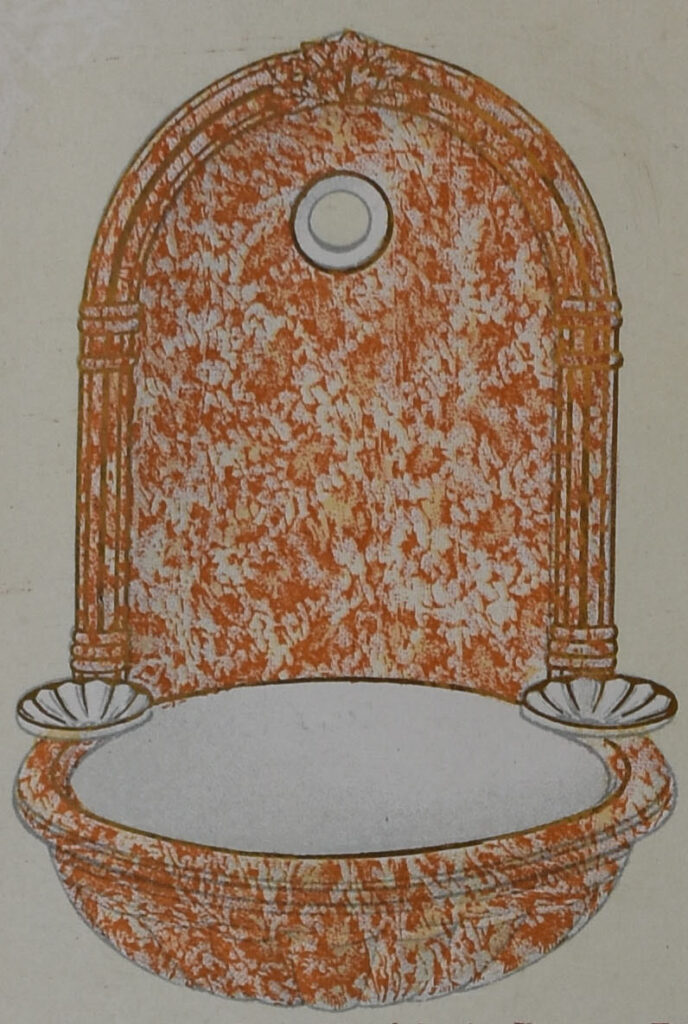

When Edward Johns Jnr took over the pottery it was producing white sanitary ware with a bit of decoration and rather plain. During the last decade of the 19th C though the products became more imaginative and gloriously decorated. In 1900 he sold the pottery to Alfred and Edmund Corn.

Josiah Spode had married Helen Heywood in 1848 but they had no children and when she died in 1868 his niece, Helen Gulson, came to live at Hawkesyard. They both converted to Catholicism in 1885 and in his will he left his whole estate to the Dominican Order for the erection of a Priory and church which started being built in 1896. The church was designed by G. Goldie in the English Gothic perpendicular style and was consecrated in 1899.

The pottery, now owned by the Corn Brothers, retained the Edward Johns name for another sixty years and was run by Edmund Richards Corn who moved into Edward Johns’ home – the Mount. His brother remained in the Potteries running their tile company – Henry Richards Tiles. Edmund knew the pottery business from both the manufacturing perspective as well as the sales side. In the next twelve years the company expanded considerably and also built houses for their employees like Itonia Terrace as shown here.

Handsacre Hall, which now formed part of Sir George Cheywynd’s estate, was split up and sold at auction in 1912. The largest part, consisting of 292 acres centred on the Hall, was sold to Francis Villiers Forster. He however lived at Longdon Grange so it was farmed by Mrs Boycott and Miss Harvey.

Like most other places, the 1914-18 war had an enormous impact on the village. The male population of the Parish aged between 12 and 40 in 1911 was just under 400 and the current records show that over 300 men from the village served in the conflict. Of those, the War Memorial records 46 names although some from the village are on other villages’ War Memorials. For more details on the fallen the booklet by Roy Fallows entitled Armitage with Handsacre Soldiers of the First World War is available from the Ridware History Society. To see a list of villagers who were in the forces in The Great War please visit the Military Records section.

Armitage County Council School – a Council school as opposed to a Church funded school – was opened in 1915 and the pupils transferred from the infants school that had been operating in Hood Lane.

In February 1920, on a plot of land on the corner of Boathouse Lane donated by Hiram Morecroft, the village War Memorial was unveiled and dedicated. Originally it had 43 names on but this was later increased to 46. The Armitage branch of the Royal British Legion was formed in 1927. In 1969 it was moved to its current site at the junction of Millmoor Avenue and New Road.

1921 saw the first twelve council houses built in the Parish – at Fair View near Handsacre Hall. Four were classed as A type (non-parlour) and eight as B type (parlour). The newspaper description of the A type, which were built in pairs, was “They have a very neat little entrance hall, from which the staircase goes up; a good large living room, a scullery with every convenience, and the bath is placed in what may be called the wash-house, on the ground floor. The living room is particularly well-lighted, there being large windows, at opposite sides. In all the houses coal can be obtained without going outside, and in every case water-closets are provided.”

Over the years numerous clubs and societies have been formed and closed down before a new version was started years later. Some though are more enduring like the WI which was formed some time before 1930 and even had its own premises between 1947 and 1983, although the WI has now also closed (2021).

As with most places in England, WW2 had a major impact. The village changed in many ways with roads being altered and the army and later prisoners of war being housed in one of the big houses – the Towers. The Civil Defence forces were manned by people too young (yet) or too old to fight. Again the military absorbed vast numbers of its youth and six more died. Pat Reid’s book, A Daisy For Dorothy, describes the war for some of the Scragg family in Armitage – Florence Scragg received the news that her husband George had been killed just before the end of the war whilst victory celebrations were actually taking place.

Just after the war the need for housing led to the creation of the houses on Chapel Road and prefabs opposite in what became Upper Lodge Road. The decision to sink a new colliery – Lea Hall – and to build two new power stations meant a big demand for housing and the result was Millmoor Avenue, Hill Top Crescent, the NCB estate at Tuppenhurst Lane and plenty more. The first work on the colliery began in 1951 with the power station following in 1956. Before the power station was actually commissioned in 1962 though the Parish lost its railway station with the Beeching cuts of 1960.

All these houses obviously generated the need for schooling and Hayes Meadow Primary opened in 1968. The impact in the area on secondary education was the closure of Rugeley Grammar School and the opening of Rugeley’s Fair Oak Comprehensive.

In 1969 the pottery, by this time called Armitage Ware, merged with Shanks of Barrhead to form Armitage Shanks. The company was bought by Blue Circle in 1980 who in turn sold it to American Standard in 1999.

Pictures

- ©OpenStreetMap contributors

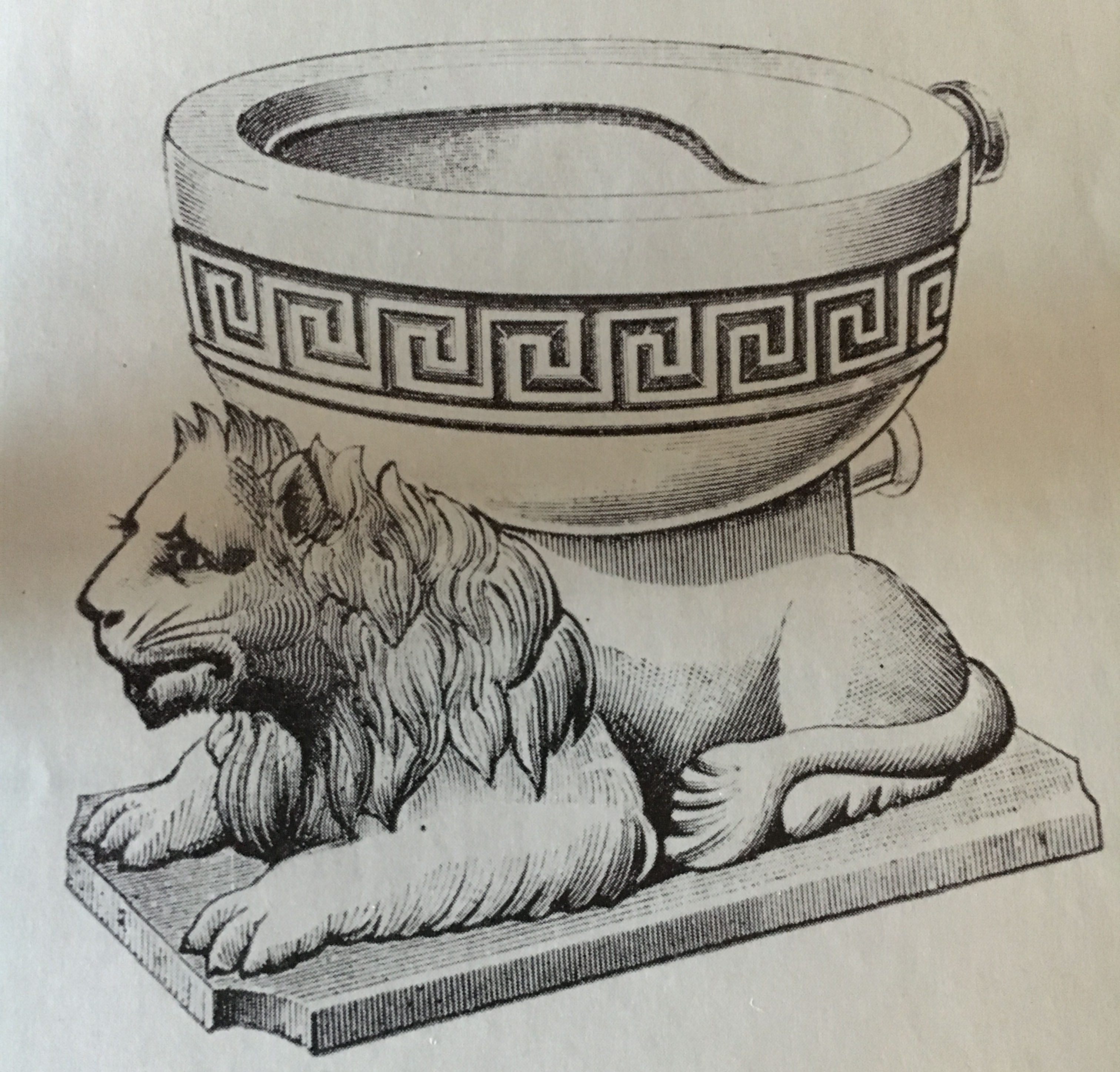

- Stebbing Shaw 1798

- Bing satellite view with permission from Microsoft Corporation

- ©OpenStreetMap contributors

- OS Opendata

- Tim Heaton/Armitage Congregational Chapel/ CC BY-SA 2.0

- Old postcard c 1910

- From May Grimley Collection

- From Armitage Shanks archives

- From Armitage Shanks archives

- From May Grimley Collection

- From May Grimley Collection