Thomas Bond is generally credited with building the first pottery in Armitage. Largely based on a set of papers held at Stafford Record Office, entitled Armitage Brickworks, this is the first of three stories about Thomas Bond. This set of events happens before the founding of the Armitage pottery as detailed in Book One History of the pottery (1809 – 1900) which is available from the Ridware History Society (RHS) via royfallows@btinternet.com. Book Two covering the period 1900 – 1945 is also now available from RHS.

John Bond, a brickmaker and maltster of St. Johns Street, Greenhill, Lichfield, married Sarah Walthall at Lichfield in 1772. They had five girls – Mary (1773), Sarah (1774), Ann (1777), Elizabeth (1786), Dorothy (1780)- and two boys – Thomas (1783), named after John’s father, and John Junior (1789). Both boys followed their father in the trade of brickmakers and maltsters. This wasn’t an unusual pairing of occupations at the time as brickmaking was done in the spring and summer whilst malting was an autumn and winter occupation.

Most pubs and large houses made their own beer but generally relied on someone else to produce the malt that was required. This was made from cereal grain, generally barley, and the farmer’s choice of variety, his time of planting, method of feeding and of course the amount of sunshine and rain all affected the quality. The grain was not supplied by weight but by a volumetric measure known as a strike which was equivalent to 2 bushels or 16 gallons. The grain first has water added in a process known as steeping to bring its moisture content up to about 46%. After steeping the grain is allowed to germinate for a few days producing what is known as ‘green malt’.

At this point the malt is heated in a kiln to halt the germination process and the amount and duration of heating produces different flavours and colours of the malt. The malt was then supplied to the brewer who completed the process either making ale or adding hops to make beer.

Brickmaking doesn’t need any great investment and it is unlikely that the Bond family physically made any bricks; they organised the brickmaking, rented the brickyard, sold the products and, eventually, got paid for the products. As well as bricks of all sorts e.g. coping, fire and arch bricks they also make roof tiles, floor tiles, quarry tiles, pipes and culvert bricks.

Bricks were essentially made from clay and the geological era that had formed it e.g. Jurassic or Triassic, altered its constituents. Staffordshire clay is largely carboniferous which is a form of shale associated with coal. It is known as ‘mild’ clay and does not need anything added to it to make satisfactory bricks. Clay particles are almost two-dimensional and essentially slip across each other making it plastic. It will stick to anything particularly when wet and it can be moulded into shapes e.g. bricks but when it is heated to a high enough temperature it becomes rock hard.

The people who physically made the bricks worked as a team with the leader who actually moulded the clay into the brick shape being paid all the money – he then paid his team who quite often included his children. The clay, which been dug out the previous autumn, was tempered by adding just enough water to reach the right consistency and mixed – by treading it and almost certainly barefoot. The tempered pile was then covered to stop it drying out (or getting too wet if it rained). The tempered clay was taken to the moulder’s bench when needed. The brickmaker sanded and then wet his mould before throwing the clay onto his bench a few times to make sure there was no air left in the mix and then throwing it into his mould. The brick maker removed the excess clay from the edges and top of the mould and the moulded wet brick was turned out onto a board or straight onto a prepared flattened drying area. The wet bricks were spaced out so that the air could blow round them and straw strewn over them to create a waterproof layer. Before going in to the kiln the bricks had to dry thoroughly and this could easily take a month. When dry the bricks were burnt in a kiln at 1000+°C.

On leaving home Thomas stayed fairly local and later documentation suggests that he ran the brickworks at The Beatings in Lichfield which was an area between Cross In Hand Lane and the Stafford Road. By 1807 Thomas was working in Armitage as a maltster and brickmaker and both buying and renting land.

On one occasion he bought land from Thomas Alldritt and the property in question apparently had a slightly uncertain status, so Birch & Yates of Brereton were asked to resolve the problem. Mr. Thomas Birch of Armitage Lodge undertook the actual work and he confirmed that everything had been done correctly when Thomas Alldritt had obtained the land from a Mr. Watson. Despite this, the land was not properly handed over until Mr. Birch ‘got the feoffment perfected by livery of seisin by Mr. Alldritt’. Feoffment in English law during the feudal period was the usual method of conveying a freehold or fee and ‘livery of seisin’ means demonstrable delivery of possession.

To do this Thomas Birch, Thomas Alldritt and Thomas Bond all physically stood in the land to be handed over. Thomas Alldritt then stated his intent to hand over the land, pointing out the boundaries, and physically giving a clod or piece of turf from the land to Thomas Bond.

In 1808 Thomas, together with George Averill, a wheelwright from Armitage, purchased hay and grass from Mr Evans. Thomas Birch was brought in to draw up a bond of indemnity against dower in Thomas Bond’s favour. A dower is a gift, often of land, given by a man to his wife on their marriage from which she could derive some sort of income in the event of him dying and leaving her a widow, this bond protected Thomas against such a potential claim. In November 1808 George Averill became bankrupt and Averill’s creditors threatened to seize the hay and grass that they had jointly purchased. Following advice from Thomas Birch the hay was removed to a place of security, probably at The Beatings or at Thomas’ father’s home in Lichfield.

Thomas also deposited deeds with Birch & Yates as security against several sums of money advanced by them to him. In early 1809 Thomas made a number of attempts, through Birch & Yates, to get a £500 mortgage without success and in early April 1809 Thomas Birch himself advanced him the money.

Later that month, 12th April 1809, Thomas Bond married Elizabeth Lovatt at Stone by licence. The licence was guaranteed by Forrester Rhodes, a victualler, of Newcastle-under-Lyme and was required because Elizabeth was under 21. In fact, she was only just 16 years old. They both stated that Stone was their own parish, but this was clearly not true in Thomas’ case and Elizabeth was from Penkridge so maybe not true in her case either.

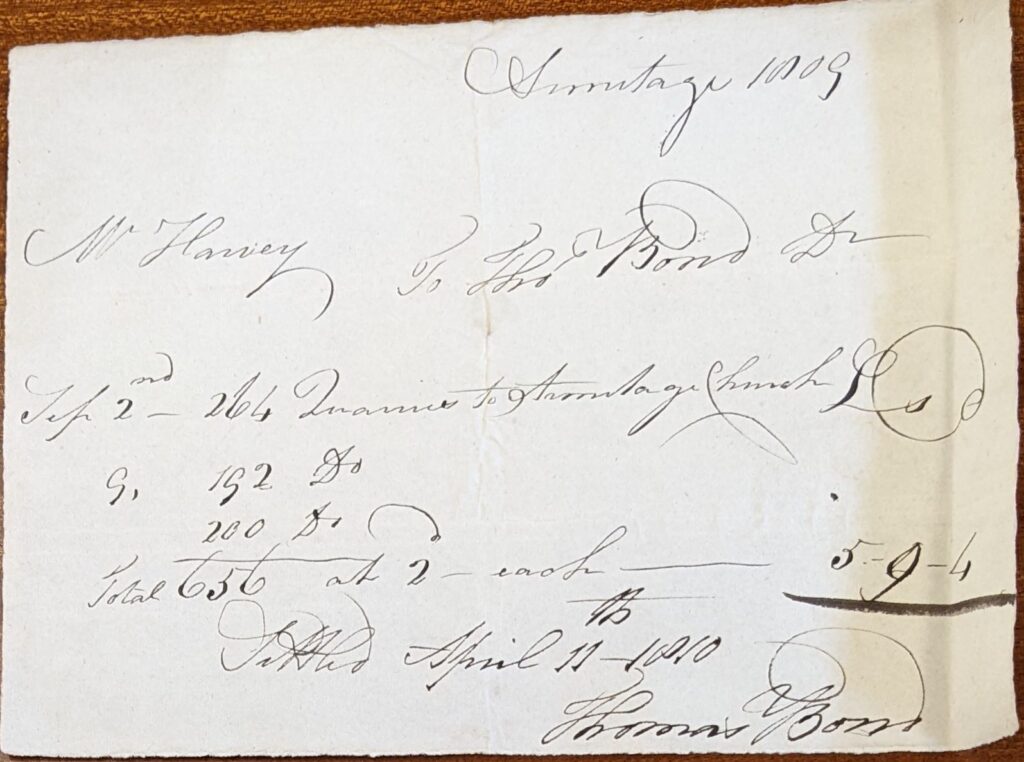

The couple lived in Armitage where Thomas still worked as a maltster and brickmaker. The image below is from Armitage churchwardens’ accounts showing Mr. Harvey, a churchwarden, paying for 656 quarry tiles used to repair the floor of Armitage church at 2d per tile – over seven months after delivery.

By the end of 1809 Thomas became involved in a pottery in Burslem. Thomas Bott had been making lusterware and earthenware pottery under the name Bott and Company and Thomas Bond joined him in a partnership. The actual manufacture was done by artisan potters whilst the two partners provided raw materials, a place of work and sold the products i.e. they funded the business.

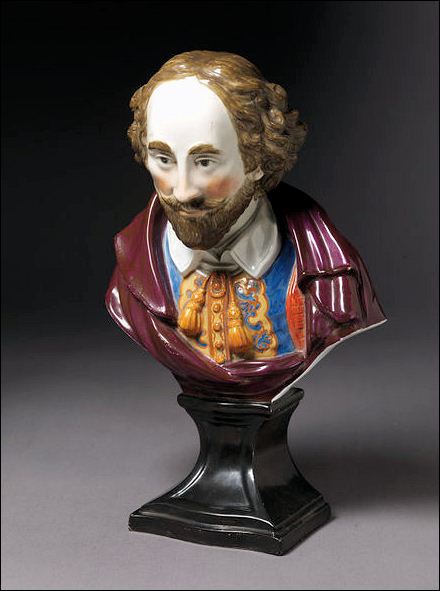

Little is known about the firm’s full product range, but the V&A Museum holds two items made by the firm and as you can see these were quite elaborate with a number of different processes used in each.

Flower stand of lead-glazed earthenware, moulded in relief, transfer printed in purple and painted in red and blue. Bowed front, flat, supported on three small feet. The front is moulded with three arched compartments below a border of discs, painted red. In each compartment is transfer-printed a view of a country house.

Bust of Shakespeare, wearing an embroidered coat, a white shirt with loose collar fastened with tasselled yellow cord, and a purple cloak thrown over the shoulders. Supported on a black pedestal with slightly bowed front.

The partnership didn’t last long though and it was dissolved in 1810 (not long after the birth of their first son, John,) – as shown by this entry in the London Gazette:

Notice is hereby given, that the partnership subsisting between Thomas Bott and Thomas Bond, of Lane End, in the County of Stafford, potters, trading under the firm of Bott and Company, is this day dissolved by mutual consent; and that all debts owing to and from the said Copartnership will be received and paid by the said Thomas Bond, by whom the business will in future be carried on – Witness their hands this 1st Day of May 1810.

Thomas searched for another partner and brought in Henry Slater. After another 12 months operation, in May 1811, that partnership also dissolved, and this time Thomas gave up the pottery operation and concentrated on his work in Armitage.

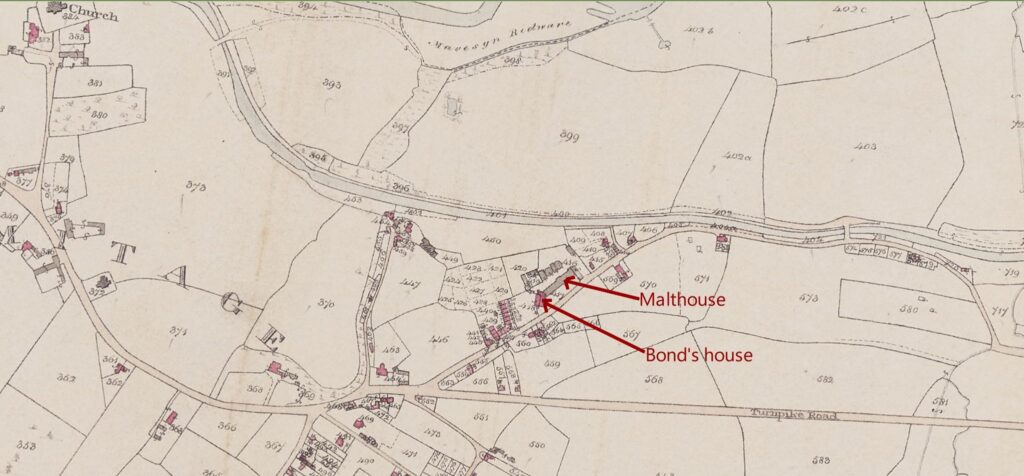

He lived down the Old Road in the house adjoining the malthouse and a single line in a document shows him renting one third of the malthouse as well as the adjoining house at a cost of £20 per annum. With the house was a brewhouse and Thomas brewed his own ale and given that the records show him buying hops you would assume that he also brewed beer. Thomas Alldritt and Thomas Smith rented the remaining two thirds of the malthouse – they had a partnership as maltsters, brickmakers, corn dealers and potters.

The company records show that they received strikes of barley from a wide area e.g. Drakelow, Lichfield, Shirleywich and Burslem. Quite often the barley was malted for the grower e.g. Toye at Brereton but it was also sold to local pubs e.g. the Swan at Rudgeley (sic) or the Boat Inn (sic) at Armitage.

The clay deposits that were dug for his brickmaking also gave Thomas access to gravel which he sold to the parish for repairing the roads which at the time were a parish responsibility. Later documentation shows that his brickyard was called Stafford County Brick Yard.

Thomas was a Protestant Dissenter (Non-Conformist) and wanted to be able to practise his religion in the village but at the time there was no option for that, so he decided that change was needed. All dissenting congregations were required to register their meeting place with the clerk for the County, so Thomas registered his own house as a chapel for the Independent Church (later called Congregational Church). Thomas’ petition for the registration was witnessed by Thomas Alldritt as well as by Samuel Brown and Andrew Shawyer – the latter had been appointed the first regular minister for the Independent Church in Rugeley in 1810. The house was registered on 23rd November 1811 just three weeks before his second son, Thomas (Junior), was born.

In 1813 his brother John joined him at Armitage and Thomas rented a house for him from Mr. Evans. Like Thomas, John also rented fields near the old Hawkesyard site. During that year the brick kiln needed repairing and they decided to build a second kiln and a small cabin. The repair and building work were done by Isaac Bradbury for £13.

At a stock take in Armitage (for the tax man) in April 1813 the following figures were given:-

Burnt i.e. fired bricks in stock area and cabin 127,370

Burnt bricks in new kiln 20,630

Burnt bricks in old kiln 19,330

Burnt bricks in different parts of Yard 3,680

Unburnt bricks 515,000

Workers were mainly paid in cash but occasionally they chose a lower sum plus meals – the meal route was chosen by William Marklew when he went from Armitage to do some work at Ridware – the meals were provided by Mr. Bromsgrove who actually owned the land on which the Ridware brick yard operated.

The example below shows the money paid to George Brown at the end of May and it suggests that 1,000 tiles were either different or perhaps sub-standard so maybe this was only paid after the bricks were burnt and the results could be seen. The calculation for the clay digging is incorrect and George was overpaid as 16s is 192d and at 4d per yard that should have been for 48 yards rather than the 40 yards he actually dug.

4,100 tiles at 2s 9d per 1000 £4-18s-3d

1,000 tiles at 2s 1d per 1000 £1-1s-0d

2 days + lad getting out foundation for arches 9s-4d

40 yards clay digging at 4d 16s-0d

Thomas’ first daughter was born in July 1813 and the couple decided to have all three children baptised at St. John the Baptist, on 31st October 1813.

With his brother on hand to help look after the brickworks and malting, Thomas decided to have another go at operating a pottery in the Potteries. Working on his own this time he rented out premises in Lane End from John Bott so this may have been the same pottery that he had operated a few years earlier. John Bott actually put the pottery up for sale in March 1814 describing it as ‘A Capital Set of POTWORKS, conveniently situated in the Markey-place, in Lane-End, and adjoining the Rail Road-Street, that goes to Stoke Wharf’. It is possible that Thomas bought the pottery but there is no evidence to support this, and it is more likely that he simply rented it from whoever owned it.

Whilst Thomas focussed on getting his pottery up and running the brickworks at Armitage and Rugeley prospered although there is no mention of Ridware so presumably he had given up the lease. In one month alone in 1815 the Navigation Company (Trent & Mersey canal) bought 71,000 bricks.

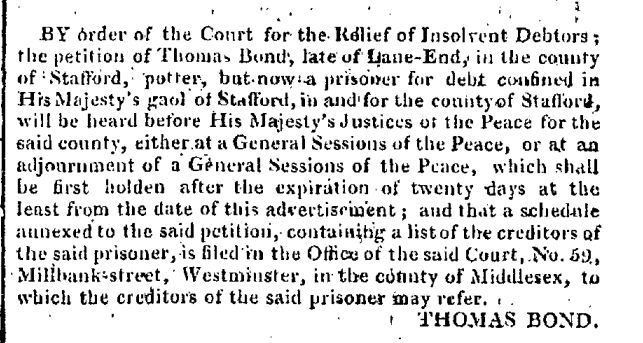

The pottery was not doing well however and in May 1815 the brick company paid Thomas £200 to help finance the pottery, followed by £100 in both July and August. Thomas still couldn’t satisfy his creditors and one (or more) of them took action. Before 1869 people could be imprisoned for commercial debt and although they weren’t considered criminals the creditor could apply for them to be held there. As you can see from the cutting below from the London Gazette by September he was in Stafford gaol. His second try at running a pottery had failed.