Roy Fallows has chronicled the lives of the 46 Armitage soldiers who died, as recorded on the War Memorial, in his book ‘Armitage with Handsacre Soldiers of the First World War’ (available from the Ridware History Society.)

On the Records section of this site under the heading, The Great War, you can find a list of the nearly 300 men from the village who actually served in the war together with details of another 11 men associated with the village who were killed in the war but are not commemorated on the war memorial.

Many of the survivors had also been wounded or gassed or otherwise injured. On walking around the churchyard, you can see a number of gravestones for those who died in the war and also for some who died after the war. The gravestone below caught my eye and at first I thought that he was a serving soldier when he died in 1931 but that was not the case – it was obviously important to him and his family to record the regiment that he had served with some 12 years before. Researching his story led me to look at others and below are the stories of just four of the men – Percy James Collop, Philip Edward Bartlett, William Pedley and William Waltho. No doubt there are similar stories that could be written – if you know of anyone whose story should also be told, please let me know.

Percy James Collop

Percy was born in Huntingdonshire in 1886 in the village of Holywell cum Needingworth. The 1891 census shows him with his parents and three brothers but by 1901 his brothers had left, and he was working as a grocer’s porter. A Henry Collop, possibly Percy’s brother, was killed in the Boer War and maybe this inspired Percy because he soon joined the Suffolk Regiment. In 1910, after his time in the Colours had been completed, he married Margaret Haynes at Newport, Isle of Wight, and their first son, also called Percy, was born nearby at Carisbrooke.

They moved to Armitage shortly after, probably because his brother Harry was working nearby at the kennels in Upper Longdon. Percy worked down the Brereton pit and they had a second son, George, in 1913. Germany declared war on Russia on 1st August 1914 and Percy, as a reservist, was immediately called back to the 2nd Suffolks. As part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) they actually landed in France on 15th August 1914, the day before the UK declared war on Germany. The 2nd Suffolks took part in the first major battle between the BEF and the German army at Mons on 23rd August and by 25th August they had retreated to Le Cateau. They served as the rearguard of the retreating BEF and occupied high ground nearby and on 26th August they came under repeated attacks, from infantry, shell fire and machine gunfire. Their commander Lt. Col. Brett was killed, and the Germans massed for a final attack at 2.30 pm and called on them to surrender. Attacks came from the front and right flanks, but the battalion was only overrun when the Germans managed to work their way round to the rear of their position. Out of 28 officers and 971 other ranks who started the Battle of Mons only 2 officers and 111 other ranks escaped. Private Collop was captured along with over 500 others.

At this stage of the war there were no facilities for handling prisoners and no prisoner of war camps. Most of the men were wounded and all would have been kept outside, probably in a wire cage. Once the camps were built the prisoners were transported to them and reports show that they often received a hostile reception if their train stopped at stations.

Percy was taken to Doberitz, which became a very large POW camp, about 8 miles from Berlin. Everyone had to work, out of the camp by 6 o’clock, working all day on very little food. As can be seen below, the work was often making or repairing roads, or some other construction. If the guards thought you were slacking, they would start prodding the men with their bayonets.

Alf Bastin was also at Doberitz and, as can be seen on the Imperial War Museum website, he recalled that the work could be dangerous. We were going out into the woods and digging up gravel which was required for building purposes in the camp and town. We used to have one of these huge farm carts, fill it with gravel, and it was dragged by about 24 prisoners. Where we were working there was quite a steep hill down to the exit. On one occasion we had started down the hill and the idea was that people holding the ropes would hang on back behind to steady the vehicle. But unfortunately, one day something went wrong and the cart started away on its own. The cart ran over one poor lad, right over his head and he was killed.

Food was poor and in short supply. A typical day’s ration was a piece of bread, often rye, and a plate of sauerkraut. The prisoners produced their own camp magazine called The Link in which there is a recipe for a jam tart.

Take 6 ration biscuits, dip them in water, and reduce to pulp in a bowl; spread the pulp evenly on a plate and strew over with a few fragments of margarine, cover with a piece of cardboard and place in the ashes under the stove. When the cardboard has burned through, the tart is done. Blow off the ashes and serve with jam or syrup.

As you might expect everyone suffered malnutrition and lost considerable body weight. When he returned to Armitage in early 1919 he was a mere wreck of his former self.

He eventually returned to a job down the pit and in June 1923 he suffered a serious injury when his foot was badly damaged. He was off work for nearly two years and the village really rallied round to help him and his family. On one occasion, in October 1924, they held a Whist Drive and Dance at the Club & Institute to raise money for him. There were 36 tables for the whist i.e. 144 players and over 200 at the dance.

On 12th August 1931 he met with another accident at a pit owned by the Cannock and Rugeley Colliery Company. He was taken to the Hednesford Accident Home and then to Staffordshire General Hospital where he died four days later. Rev. W. W. Holdcroft in the funeral service stated ‘He was numbered amongst those who, at the call of King and country, left all that was dear to them, endured hardships, faced danger, and offered to give up their lives that others might live in freedom. Let those who came after see to it that his name be not forgotten.

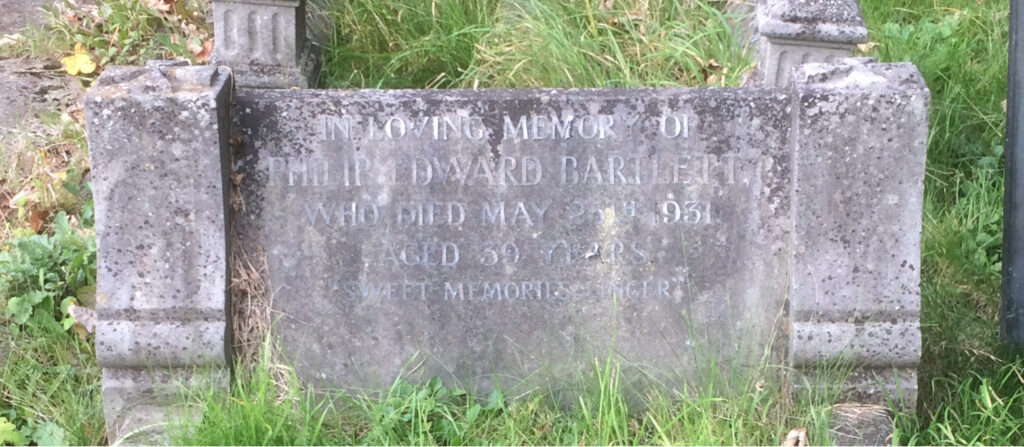

Philip Edward Bartlett

Philip was born at Folmer Lodge, Penkridge but the family moved to Armitage when he was about five years old. His father ran a farm down Hood Lane and their home was a 15th C timber framed house.

He and his brothers and sisters helped run the farm but when the war came along he joined up with the earlier batches of Armitage lads and went into the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. During training he won the company prize for marksmanship and by Spring 1915 he was fighting in the trenches in France. He was transferred to Salonika in the summer where he took part in the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign before the Allies withdrew in January 1916.

In October 1916 he was sent to hospital with dysentery and was, for a short time, invalided home before heading back to the front line. Spring 1917 saw him back home again, on leave this time, and he was even able to help his father with the sowing.

By now he had been appointed a Lance Sergeant which is an appointment given to a corporal so they can fill a post usually held by a sergeant – he would have had a Sergeant’s three stripes on his sleeve. In October 1917 he was blown up by a shell and received extensive shrapnel wounds in his back. After a spell in a hospital close to the lines he was transferred to a hospital near Manchester. In December his brother Len, who was with the North Staffs, was also in hospital – he was suffering from shell shock after being blown up whilst he and a friend were acting as a stretcher party moving a wounded man ‘down the line’.

Philip spent the majority of 1918 in hospital and never returned to the front line, being demobbed in February 1919. His brother, Len, was captured by the Germans at Mariecourt in their 1918 Spring Offensive and spent the rest of the war in a POW camp – he was eventually demobbed in March 1919.

Philip obviously had extensive injuries given the length of time he was in hospital but it wasn’t all bad – his nurse was a Hilda Percival who he married in 1920 in Bolton. They returned to Hood Lane where he worked on the farm and had three daughters.

His problems as a result of his injuries got progressively worse however and early in 1931 he entered Staffordshire Infirmary for further treatment but it was found that too much damage had been done. He returned home after a short stay and died, at home, on 25th May 1931.

The Lichfield Mercury carried the following piece on 5th June 1931, written by a member of the British Legion.

The tribute paid to the sterling character of the late Philip Bartlett of Hood Lane farm, Armitage, at his funeral by the Rector, was a remarkable one in many respects, but that it was in no way exaggerated for the occasion all who knew him can testify. As a soldier it was never my privilege to serve in the same regiment as him, but those who did give him the highest praise. In civilian life he was a man of extraordinary good feeling and generosity, and his cheery “good morning” as he went on his daily round of the village was as good as a tonic. He was never heard to speak harm of anybody, and his name was never mentioned but in the friendliest manner. He was true and honest in all his dealings. When he last returned home from hospital, though practically a doomed man, he kept up his courage, and his many friends who visited him during those few weeks before his death were amazed at the fortitude he showed. His wife, although the strain must have been great, nursed him to the end. And their married happiness ended as it began – the attentive nurse and the wounded soldier.

Philip Bartlett died for his King and country just as if he had died a speedy death on the battlefield instead of a lingering death at home, but owing to there being a time limit of seven years after which no claim for pension is allowed his wife did not receive a war pension. The British Legion appealed in vain.

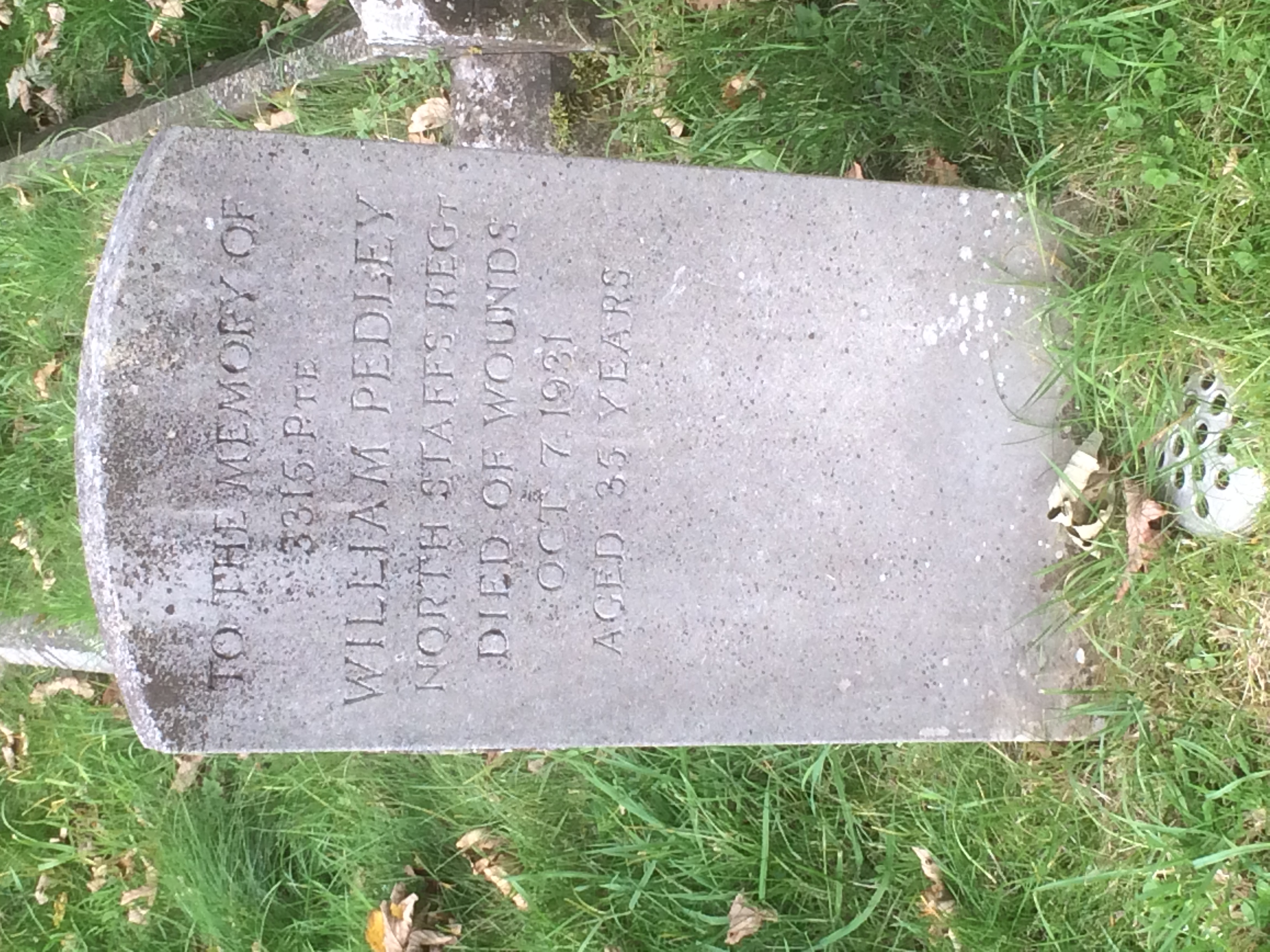

William Pedley

William was born in Stoke-on-Trent in 1895 but his family moved to Armitage in about 1906 where his father and brother both worked, as mould maker and presser respectively, at the pottery. His brother Henry married a Handsacre girl, Ada Lear, whilst his sister, Hilda, married a Rugeley lad, Benjamin Hollins.

The 1911 census shows Henry, with his wife and son, in Old Road whilst Benjamin and Hilda, with their two children, are living with William and his parents and younger sister at 2 Ricardia Terrace. William is shown as 16 years old and an invalid.

The Terrace was only built in 1911 and consisted of 12 houses which were built by the pottery for their workers and everyone who lived there worked for the pottery.

When war broke out almost all of the 12 houses provided soldiers for the front – at least 17 men from this small terrace served in the forces with three being killed. I do not know why William was classed as an invalid in 1911 but by 17th November 1914 he was obviously fit enough for the army because he enlisted in the Staffordshire Territorials. Whilst he was undergoing training he heard the news that his brother-in-law Benjamin Hollins, also in the North Staffs, had been killed in the fighting at Ypres.

After his initial training he was posted to Ireland where he was stationed in Dublin during the Easter rebellion. He transferred to the North Lancs and almost immediately he was involved in the Battle of the Somme which began on 1st July 1916. His battalion was at Beaumont-Hamel which was near the northern end of the 28 mile front. After the first month of the battle the area was relatively quiet but in the final act of the Somme Offensive the allies launched the Battle of the Ancre at Beaumont-Hamel on 13th November. William was blown up and suffered severe injuries and was returned home to Hampstead Hospital. Just over a year later he was invalided out of the army on 7th December 1917 by which time he had married Elsie Sanders.

They lived in Pike Lane and had four children, all girls. William ran for both Parish Councillor and District Councillor and in the newspapers William’s occupation is shown as Army Pensioner so they must have managed on William’s disability pension from the army.

In October 1931 though William died. On Friday evening, 2nd October, his wife had gone to bed and realised some time later that William had still not come to bed. She went downstairs to find him lying unconscious on the floor. Dr. Whiteside was sent for but he never fully recovered consciousness and died on the Sunday morning. His war injuries were given as the cause of death.

The funeral took place on 7th October and after the committal part of the service a firing party from the North Staffs fired three volleys over the grave in farewell to a former comrade.

William Waltho

William was born in Pike Lane, Armitage – the fifth child of Samuel and Emma (nee Brain), in 1881. His father had a number of different jobs over the years – at the pottery and at the pits – and William was followed by another four children, including twins in January 1890. Just a month after the twins had been born though his father was killed in an accident at the pottery when he was caught in the milling machinery. By this time William’s older brothers were already working at the pottery and at different times all six of Samuel Waltho’s sons worked at the pottery.

By 1911 William was working away from the area and his widowed mother was living at 6 Ricardia Terrace, just along from the Pedley family. His brother Albert, sister Mary, and the twins were also there. In order to help make ends meet his mother had taken in a boarder – Arthur Arthan – who, along with her sons, worked at the pottery.

When war broke out William was working as a bricklayer and he was called up in May 1916. His three younger brothers also joined the army. William joined the Royal Engineers and after his training he embarked for France on 13th December 1916. Whilst there he received news that his younger brother Albert, who had fought in the Battle of the Somme, had died of wounds. This was quickly followed by news that his mother’s former boarder, Arthur Arthan, had also been killed.

Some time early in 1918 William was very badly gassed and on leaving hospital in April he was posted back to the UK. He was demobbed in February 1919.

It has been estimated that gas was responsible for less than 1% of the casualties but for over 25% of soldiers being admitted to hospital. It was, quite simply, a weapon of terror. In 1916 the army had introduced box respirators that were effective against most gases but they were not easy to put on and were cumbersome to wear.

This excerpt from Wilfred Owen’s poem, ‘Dulce et decorum est’ gives a very graphic description of a gas attack when one of the soldiers failed to get his respirator on:

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling, And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime ... Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning. If in some smothering dreams you too could pace Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin; If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Studies after the war found that even mild exposure to the gases used in the war could lead to a wide variety of problems including palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, photophobia and laryngitis.

William returned to his job as a bricklayer and lived with his mother at 6 Ricardia Terrace. He continually suffered from severe stomach pain and I have no doubt that he suffered from PTSD but that condition wasn’t recognised at the time. In 1925, when he was helping to build the houses at Greenfields Avenue for the pottery, it all became too much to bear and, sadly, he took his own life. His mother, Emma, had lost a second son to the war.

There are newspaper reports on the inquest but none of the funeral so there are no great stories written about him. Unlike the other three men in this story, I have been unable to find a gravestone. He gave his life for his King and country just as much as they did and he deserves to be remembered.