While some sources, like the British Listed Buildings website, refer to this property as simply a 17th C timber frame building known as The Croft of Mavesyn Ridware, the true story of Lodge Cottage of Armitage is far more intricate and fascinating. This 17th C timber-framed house, with its cruck-frame origins and curious features like a coffin chute and witch mark holds secrets that date back to at least as far back as the 15th C.

Grade II Listing

The house was first listed as a Grade II protected building in 1964 and the description (below) suggests that no internal examination was made, perhaps because the owners would not allow it.

House. C17. Timber framed with brick infill; thatched roof; brick

ridge stacks. 3-cell baffle-entry plan house aligned north-south facing

east. One storey and attic, 3 square panels to eaves with straight braces.

Irregular fenestration, 5 glazing bar casements to ground floor and 2

within attic dormers to the left and centre with the roof arched over

them. Door to left of centre. Single-storey lean-to extension to the

left. Interior. Chamfered and stopped ceiling beams.

Architectural origins

At the heart of this building though is a one-bay cruck-frame building from, at the latest, the 15th C or quite possibly much earlier making it the oldest dwelling in the village. (The oldest surviving cruck house in the UK is from the mid-13th C). This original building was a single room, measuring just 6ft 3in by 11ft 8in. This original part of Lodge Cottage is less than a tenth of the size of a similar construction in Hood Lane.

It was open to the rafters with a wood fire in the centre; smoke blackening on the internal roof timbers proves both the open plan and the wood burning hearth. A thatched roof, which probably extended down quite close to the ground, completed the structure. In between the timbers, the walls would have been filled with wattle and daub. The wattle was made by weaving thin branches between stakes and daubed with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, animal dung and straw.

Cruck Construction

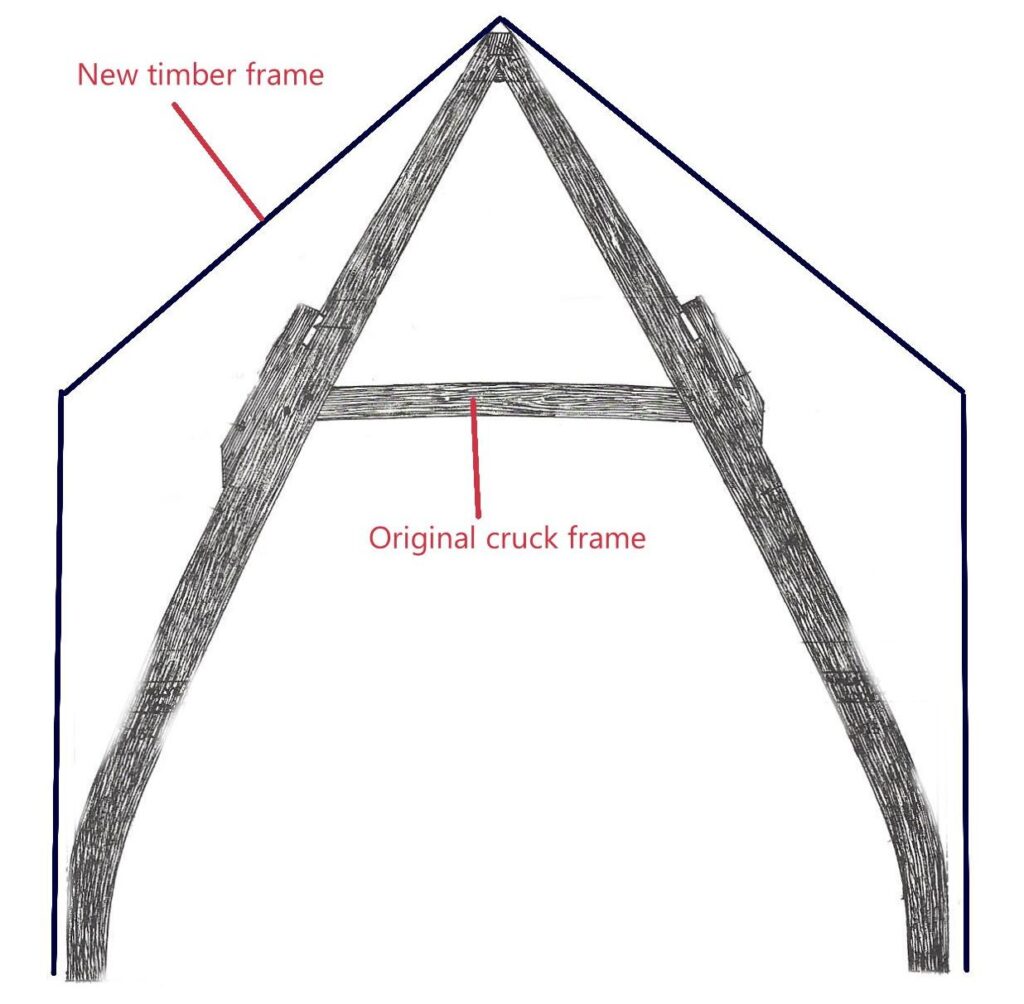

Crucks are made by selecting an oak (or occasionally an elm) with a stout lower branch, felling the tree and squaring off the trunk, then sawing it in two vertically. The result should be a symmetrical pair of curving or elbowed ‘blades’. Adding a tie beam to connect the two blades creates an A-frame, a triangular structure that is very strong and resistant to lateral forces.

The A-frame’s inverted ‘v’ shape carries the roof’s weight directly to the ground, making the structure especially sturdy. This means that the wall frames can be made using a lighter construction and the walls also use the cruck frames for support. The timber would have been felled using a two man saw and axe and then squared up with an adze. The procedure for construction would usually involve assembly on the ground and subsequent erection to a standing position. The whole cruck structure stood on a rectangular timber sill.

The introduction of coal for the fire which probably took place in the 16th C would have caused issues. Coal requires a strong draft and therefore more of a roof opening but it also produces a different type of smoke which deposits grease on surfaces. Chimneys were eventually developed to overcome these issues and the fire was moved from its central position to stand against the southern wall where the chimney, measuring 6ft 3in by 3ft 6in, was installed.

17th century alterations

With this change there was no longer a need for a large open space for the smoke to dissipate through the thatch. Despite this available space crucks do not lend themselves easily to the construction of upper storeys. The curvature and the height of the cruck blades also places a limit on span, room width and headroom. Once they have been constructed they are also difficult to extend by the addition of extra bays or wings.

To make use of the space and to extend the building, probably in the late 16th or early 17th C, it was effectively encased in a timber frame. This timber frame is essentially a rectangular timber box resting on a stone plinth. The timber beams were arranged in a vertical, horizontal and diagonal pattern. Once the box structure was in place the purlins and rafters were taken off the cruck frame and installed on the new timber box frame. Figure 3 shows the enlarged structure after the addition of the timber frame, highlighting the increased height at the room edges. As the thatch followed the roof line Figure 3 also shows how much lower the thatch went with the cruck frame.

This first timber box frame may originally have been only around the one bay cruck frame but it allowed the insertion of a new floor. This necessitated the installation of a set of stairs and allowed the installation of an attic window under the thatch. These stairs no longer exist but they were so steep and narrow that it was impossible to move large or heavy items up and down them. What appears to be a coffin chute was therefore put in – see Figure 5 – so that heavy items could be carried up or brought down from the first floor e.g. a coffin, hence the name. A coffin chute is essentially a hole cut into the ceiling with a hatch installed to cover it. It is also called a coffin hatch or coffin drop.

Over the next hundred years or so a number of extensions were added. The north side (see Figure 4) was originally an animal shelter with a dirt floor but it was eventually converted for residential use. The south side was extended more than once resulting in a second chimney and a second attic room and window and subsequently a third chimney. At the southern end of the building a large bread oven was installed – the chimney for this can be seen just peeking above the roof, second from the left in Figure 7. In the grounds were a well, an outside privy and the building shown in Figure 8 although there are no indications as to what that small building was used for.

The 16th C saw a rise in fear of witchcraft and malevolent forces especially during the reign of Elizabeth I when belief in the occult was prevalent. During this period witch marks were often etched or burnt into fireplaces, door frames, and windowsills as these were considered vulnerable points where evil could enter a home. At least one witch mark – see Figure 9 – was placed on a door frame for Lodge Cottage although the timber has now been repurposed and sits above the cooker.

Recent History

By the start of the 19th C the building was part of Armitage Lodge estate and had been divided into two cottages. It was used to house employees of the Lodge with the most famous of those occupants being Antoine Albena Mountsoy, who is the oldest recorded inhabitant of Armitage. When Mr. R. Moore bought Armitage Lodge in 1925 Lodge Cottages, as they were then known, were not included in the sale.

In the early 1950s, the cottages were both bought by a Mrs. Hewitt who converted them back to one cottage and made extensive repairs. Not long after the Shaw family bought them in 1957 the cottage was rethatched as shown in Figure 10. This view shows that one of the attic windows had been blocked up and a door on the far right had been replaced by a window.

An unknown artist painted the cottage after it had been rethatched and the second attic window had been reinstated. The painting, Figure 11, also shows that, at least for a time, it was called Cuddy Cottage.

In the early 1980s the thatch was renewed and as part of the rethatching the bread oven is believed to have been removed. A rear extension was added in 2000 at which time the third chimney was removed leaving the profile as shown in Figure 12.

Lodge Cottage has recently been rethatched and the process revealed more elements that are normally hidden from view as shown in the photographs below.

From its 15th century origins to its recent rethatching, Lodge Cottage stands as a testament to the evolving history of Armitage-with-Handsacre. I would like to thank the current owners, Paul and Berry Wilson, for providing photos, records and allowing me access to this wonderful building.

I think I remember the Lodge being re-thatched while I was living in the area, so must have been the late 60s/70s? I remember the Shaws very well as Mr Shaw was in the choir as pretty much a permanent fixture, even after the choir at St John’s was decimated when Sunday sport became a ‘thing’ and the choirboys disappeared to football practice. Another fascinating article, Richard; I have never heard of ‘coffin chutes’; that brings to the imagination all sorts of ghastly imagery! I always thought the cottage was such a beautiful place, but I bet the spiders love the thatch…

Thank you for another wonderful history record. It would be good to have some of these photos in the village hall collection.

I shall sort that out with Roy.