It took a bit of time to set up the system and the Lichfield Poor Law Union wasn’t established until 21st December 1836. It’s operation was overseen by an elected Board of Governors, 40 in total, and at first Armitage did not return a Guardian but eventually, in 1842, Thomas J Birch Esq was elected. One of the first tasks for the Guardians was to erect a new workhouse big enough for the poor of over twenty parishes and in May 1840 it was ready to receive it’s first inmates – the very term ‘inmates’ suggests a place you would want to avoid.

The New Poor Law spells the beginning of the end for the system that had grown up to administer large parts of parish life although parish officials did continue with some duties. Very few records were made by the Overseers after 1840 but there is a single document in the parish records, inappropriately dated 25th December 1841, that gives a little bit of information about Armitage inhabitants of the new workhouse.

It records the names of Armitage residents who had been at the workhouse in the three months up to that date. It shows that Hannah Lunn (28), and her four young children, Henry (6), Emma (4), Harriet (3) and John (2) were all taken into the workhouse just a fortnight before Christmas. There are another six Armitage residents there who had been the workhouse for at least three months:

- Martha Waltho, aged 61

- Hannah Waltho, aged 38

- Mary Waltho, aged 9

- Mary Mathers, aged 21

- Charles Mathers, aged 1

- William Warren, aged 49

Presumably there was insufficient room for everyone in the workhouse because there were still seventeen people from the parish who were receiving out-relief as shown in the table below. The right-hand column shows the costs for each individual for the previous three months.

| Surname | Christian name | Age | Residence | Cause | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alldritt | Elizabeth | 74 | Atherstone | Infirmity | £1 12s 6d |

| Alldritt | Catherine | 76 | Armitage | Infirmity | £1 14s 5d |

| Bradbury | Henry | 22 | County Asylum | Insanity | £3 18s 0d |

| Day | Ann | 73 | Brereton | Infirmity | £1 1s 5d |

| Greatorex | Sarah | 64 | Armitage | Infirmity | 19s 11d |

| Henney | Ann | 74 | Longdon | Infirmity | £1 14s 4d |

| Lunn | William | 84 | Armitage | Infirmity | £3 15s 4d |

| Lunn | Thomas | 72 | Armitage | Infirmity | £3 8s 10d |

| Munday | John | 69 | Armitage | Infirmity | £3 15s 4d |

| Mills | John | 81 | Armitage | Relief & funeral | £2 5s 8d |

| Robinson | Lucy | 61 | Armitage | Infirmity | 19s 11d |

| Shrawley | Mary | 58 | Armitage | Infirmity | 19s 6d |

| Vickers | Paul | 84 | Longdon | Infirmity | £1 14s 5d |

| Waltho | Hannah | 82 | Armitage | Infirmity | £2 0s 11d |

| Wood | Margaret | 89 | Armitage | Infirmity | £1 5s 0d |

| Clamp | Robert | 75 | Infirmity | 3s 11d | |

| Hackett | Ann | 68 | Infirmity | 5s 0d |

Workhouse conditions were deliberately demeaning. New inmates had their own clothes taken from them and were issued with workhouse clothing. This clothing was more like a uniform and made from very cheap materials – for economy but also as a badge of pauperism. There were plenty of other indignities heaped on inmates – the hair of both boys and girls were cropped, for instance. The diet was dreary and monotonous, largely consisting of bread, cheese and gruel, and often without salt.

After the New Poor Law came into force the village poor still had some support from charitable donations. Charities had been set up by Benjamin Bolton in 1731 and by William Oldacre in 1753 – both had left land to the parish which generated rent. The Charity Commissioners’ Scheme of 1900 states that the money from these charities should be spent on clothing, linen, bedding, fuel, tools, medicine or other aid to deserving residents of the parish. At various times Josiah Spode is also recorded donating coal and ‘fat cattle’ to the poor of the parish.

It is no wonder that the operation of the New Poor Laws had a big impact on the Parish, (and the nation as a whole). Groups of residents soon began to make other arrangements to try and make sure that they didn’t have to go to the workhouse if they were injured or sick.

Robert Hedderwick Penman had set up a new pottery in the village in 1852 and by 1859 he was partnered by John William Oslear, a banker from Lichfield. The workers created their own sick club and Oslear, who gave a substantial donation, agreed to act as treasurer. Other locals and persons connected to the company also donated money to the sick club.

Friendly Societies, who provided financial services and social activities for their members, blossomed in this period. The Ancient Order of Foresters, the Order of Oddfellows and the Order of Good Templars all had branches in the Parish. These societies had their own juvenile branches and also their own magazine, e.g. the Foresters had Foresters Miscellany. Flags, banners and regalia were all part of their identity and newspaper reports often gave accounts of their marches through the villages. The 27th June 1890 edition of the Lichfield Mercury had this report:

Handsacre “Wake” – This annual event took place on Monday, and as usual attracted a considerable number of visitors from the adjoining villages. The weather was all that could be desired, and everything passed off in a successful manner. In the morning the Foresters and Old Oddfellows’ Lodges marched in procession to the parish church with banners and flags flying, and were led by the Armitage brass band, the strains of which created the usual excitement along the route. A special sermon was preached by the Rev A. Kingston, after which the procession returned to Handsacre, and the members partook of dinner together at the Red Lion, amongst those present being the Rev A. Kingston and Dr. Chapman. At the rear of the Inn a number of swings, stalls etc were placed for the amusement of the villagers, and during the evening the band played for dancing, the latter being freely indulged in by the young people generally. The usual amount of feasting and conviviality was observed throughout the village, which during the day presented a scene of unwonted excitement and gaiety.

Another 1890 newspaper report details the Foresters benefits scheme: when a member was off work through injury or sickness , they were paid 10s per week for the first 26 weeks, then 5s per week for the next 26 weeks and 2s 6d per week thereafter. In addition a £10 funeral allowance was given on death of a member with £5 for his wife’s death. Members were also offered life assurance schemes.

In 1903 the Rev Edward Sansom was appointed to the rectorage of Armitage to go with his vicarage of Pipe Ridware. From 1870 to 1873 he had been curate of Rugeley, from 1873 to 1874 the vicar of Pipe Ridware and from 1874 to 1894 the vicar of Brereton before retiring due to ill health. In 1896 he bought the properties of the late Thomas John Birch and moved into Armitage Lodge where he became a churchwarden at St. Johns. Having recovered sufficiently to resume active work he had become the vicar of Pipe Ridware.

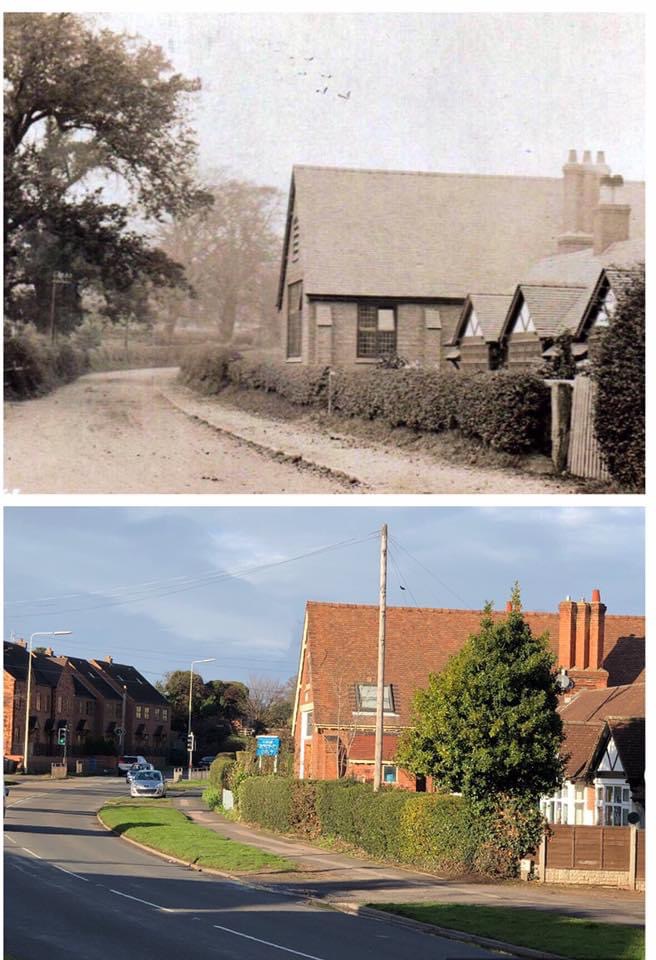

Revd Sansom was from a family of wealthy London barristers and is recorded as having an artificial leg. Throughout his time in the district, he spent considerable sums of money on Pipe Ridware, Brereton and Armitage churches. He built four almshouses in Brereton followed four more almshouses and the church hall in Armitage. The Armitage buildings were transferred to the custodianship of the Lichfield Diocesan Trust in 1908. These almshouses were exclusively for the needy inhabitants of the village. The 1911 census records four widows living there – Patience Conway (73), Mary Craddock (79), Ann Kettle (72) and Elizabeth Hackett (65).

In 1974 the properties were modernised and extended with bathrooms, better kitchens and central heating but retained their bedsit design without a separate bedroom. It was another forty years or so before they were brought up to what is now referred to as the “Decent Home Standard” and this required a major investment by means of a substantial grant from the Home and Communities Agency. A complete redesign meant that the four homes were converted into two, each with two separate bedrooms and spacious living rooms. They are now operated by “The Birch, Samson and Littleton United Charities”.

Everyone will have their own opinion as to whether the way we now care for the needy is better or worse than before. The word community gets used a lot but the parish was certainly more of a community when it was smaller. But that was only good if you were part of it rather than outside trying to get in.

The Benjamin Bolton charity still operates and is a registered charity. Invested revenue from the remaining funds still brings in over £100 per annum. Chair of the committee is Liz Coles and Secretary Diane Conway. When John Perry was on committee it was arranged that the custom of giving to the needy for coal money was no longer appropriate and when the funds had sufficient, the committee worked with the Parish Council to provide benches for the community.

The most recent donation was £1000 to the fund to restore and improve the site of Armitage War Memorial.