When researching a person the occupation begins to tell something of that person’s story although it is always more interesting when an unusual occupation is encountered. As you might expect, there is not much in the way of written information about occupations in medieval times but records of court cases provide some information.

After the death of her husband, William de Handsacre in 1282 AD, Ala his widow needed a dower so that she could remarry. She was entitled to one third of William’s landholding and she had to go to court to get it. She sued Richard le Carpenter and Thomas le Harper who were the executors of William’s estate. Although by this time these might simply be surnames rather than occupations it does suggest that the Lord of the Manor had his own harper.

A few years later (1306 AD) another court case not only introduces an old manorial occupation but also gives us one of the earliest documents about Armitage:-

Robert, son of Ralph de Pype and Emma his wife, sued John del Ermytage, Chaplain, for coming with others unknown on the Vigil of the Epiphany, 1304 AD, to the vill of Pype Rydware to the house of the said Emma and ejecting her from it and taking her goods and chattels to the value of 10s., and extorting from her a sum of 5 marks before he would permit her to re-enter her house.

John denied having inflicted any injury to her, and stated that after the death of Walter de Rydeware formerly the husband of the said Emma, who held the said tenement of Ala de Hundesakre, he had taken the possession of the tenement as custos by reason of the minority of Roger son and heir to the said Walter, acting as Seneschall for Ala, and he had held it in the name of the said Ala until Emma had made a fine of 5 marks to have the custody of it until the full age of the said Roger, and he appealed to a jury. The jury found in favour of Robert and Emma, who recovered 8 marks as damage, and John is committed to prison.

A seneschall (seneschal) can have a number of meanings but is essentially an officer in charge of domestic arrangements, ceremonies and the administration of justice.

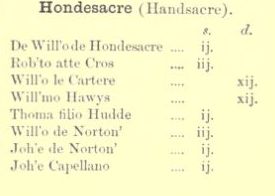

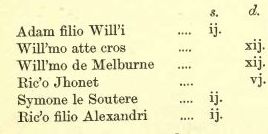

When Edward III needed money to fight the Scots his first Parliament awarded him a subsidy to be taken from all the manors in the land. The images below give the names of the fourteen from the Manor of Handsacre who had to pay and the amounts they paid. On the list is William le Cartere (a carter) and Simon le Soutere (a shoemaker). Thomas son of Hudde is also on the list – Hudde was a regular name on records from the Manor and is where we get the name of the road, Hood Lane. The name Hudde either came from someone who wore a very striking hood or more likely from someone who made hoods; peasants’ clothing for many centuries consisted of a short tunic, belted at the waist, and either short stockings that ended just below the knee or long hose fastened at the waist to a cloth belt and a hood or cloth cap.

Another court case from 1457 AD in the reign of Henry VI tells about a person whose surname derives from the occupation of an ancestor but who had himself followed a different occupation: –

Reginald, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, sued William Couper, late of Hermytage, Coteler, and Hawise his wife, for taking by force Richard Hille, his native and servant at hermitage, by which the Bishop had lost his services for a length of time and for which he claimed £10 damages.

Presumably William’s ancestor had been a cooper whilst he himself was a cuteler or knife maker. I wonder what is meant by the term ‘his native and servant’?

Records for the Manor of Handsacre appear to have been destroyed in the Civil War but parts of the Parish was absorbed into the Manor of Longdon by purchase or dowry and that Manor appointed individuals in the Parish to official positions. Ebenezer Kent and Thomas Ford were appointed headboroughs which at the time meant the same as a Parish Constable. Joshua Harvey meanwhile was appointed an ale conner and his role, (a yearly appointment), was to ensure the quality of bread, ale and beer as well as regulating the measures in which they were sold and their prices. So basically he called at all the breweries and bakeries and sampled the wares and if it wasn’t up to scratch he issued a fine.

It’s well over 300 years before we start seeing written records of occupations again. Baptism records for Armitage start recording father’s occupation in 1813 whilst marriages from 1837 record occupations for the bride, the groom and both of their fathers. Most records are not very specific, simply recording an occupation as labourer, miner or potter. In fact the 1841 census deliberately was very general – a brand new occupation of ‘agricultural labourer’ was created just for the census so we cannot see the specific role of, say, ploughman or shepherd.

Employment records from Thomas Bond’s attempt to run the pottery in Armitage have a wide range of specific occupations such as thrower, turner, saggar maker and plate maker which may be familiar plus a number of less familiar ones.

Martha Wainwright and Sarah Hinson were both employed as triangle makers. A triangle in this sense was a piece of kiln furniture which was used during the glost firing to separate pieces of glazed ware to prevent the pieces sticking together during the fire when the glaze melts into glass. They produced a range of different shaped pottery items e.g. triangles, stilts and cock spires so that different items like plates and mugs could be kept separate during glost firing. The various designs left marks on the undersides of the pottery piece but the glazed (display) surface was not marked. Where the triangles etc had made contact on the bottom of the ware they left small nodules of the triangle and glass which were ground or chiselled off.

Elizabeth Robinson, Ellen Jenkins, Lettice Bullock and Alice Cope were described as lathe turners or lathe treaders. They spent their days on what would today be called a cross trainer using the up and down motion to create a rotary motion on the potter’s wheel or the turner’s lathe.

John Edwards was a squeezer – he operated a machine which converted old bricks and clay into long sausage-like wads of clay that was used for making sure that saggars were properly sealed when in the oven thus preventing smoke and oven gases getting into the saggars and damaging the ware.

Another use of these wads was to make handles – Thomas Broom and Thomas Warburton were both handlers. The wads from a squeezer were only used for the very plain handles; ornamental handles were made using small plaster moulds. Apart from fixing handles to cups, mugs, jugs etc they also adding spouts to teapots and similar embellishments.

From the baptism record of Emma Ingram in 1828 we find that her father John was a gun barrel borer. At the time of the baptism the family lived in Brereton although most of his life he spent in Wednesfield and Birmingham.

Occupations show the small cottage industry that was needed in all parts of the country before the big wave of industrialisation and imports took away these skilled crafts. The village had its own rope spinners, like John Peters, and basket makers like the Carthy family. William Bentley was a clog maker when he married Sarah Sedgewick in 1856 although he was from Cheadle which was probably where he worked.

In a similar vein there were lots of small shopkeepers and provision suppliers often selling from a room in the house or even just a kitchen. Eliza Bond in 1860 was accused of having unjust scales and her occupation was given as huckster which is defined as a person who sells from a stall or small store, like a peddler or hawker. The term is believed to be derived from the Middle English ‘hucc’ meaning to haggle. The parish also housed various people, like Maria Dawson from Handsacre Brickyard in 1841, described as higglers who bought and sold goods e.g. butter, cheese, eggs and who needed licences.

Some occupations given in census returns are difficult to work out, often due to handwriting issues. The 1841 census for Holly Bank shows Thomas Jones and his son Edward working as ‘machine thrashers’. In 1851 Edward was living on the Plum Pudding Hills and gives his occupation as a machine and drill maker. Given these two records (and ignoring the Luddite idea) it is likely that they made and operated threshing machines and similar agricultural machinery although probably not steam powered versions.

In 1837 John Warner married Ann Moore and like his father his occupation was given as ‘jumberman’ and I can find nothing that makes sense of this occupation. Other records e.g. census for the Warner family show them as agricultural labourers, labourers or similar. If anyone knows what a jumberman did, please let me know.

And finally, one of the more bizarre jobs. Daniel Wetton, from Penkhull in the Potteries, was a boatman on the Trent & Mersey canal and frequently called at the Plum Pudding, Armitage, where Samuel Hoon was the landlord, and just as frequently got into fights. One particular fight with a fellow boatman was only ended by the police pulling them apart and Daniel ended up in front of the magistrates. In this particular case Josiah Spode IV, of Spode House, Armitage but originally also from Penkhull, was the JP. Faced with a fine and costs Daniel reminded Josiah Spode that they knew each other well when they were younger. Josiah Spode had been sent to a school from his home – The Mount, Penkhull – and Daniel who was about a year older than Josiah was paid to carry Josiah on his back to and from the school, morning and evening.

Josiah did not appear at all embarrassed by this information and not only let Daniel let off with just a reprimand but also gave him half a sovereign into the bargain.

Found this very interesting, Handsacre and Armitage in with other surrounding villages hold an awful lot of history

Hi Richard. I wonder if ‘jumberman’ could have had a badly written and elongated ‘L’ at the start, perhaps being a lumberman, one who cut and carried wood. I think it is a term still widely used in the States, but not here so much, perhaps.

Facinating to read,only been in “Armitage”since 1986.Wonderful to read the history.