Welcome to our church, a truly remarkable and ancient structure perched up on this dry, pleasant, rocky eminence. From here, we can enjoy splendid views over the rich vale of Trent, with the majestic woodlands stretching far to the north and the lofty hills of Charnwood Forest visible to the east. Just below us, between the church and the river, runs the Grand Trunk Canal, a lively artery of commerce where the daily clamour of sturdy bargemen echoes through the ancient woods and rocks—a scene quite different from the solitude likely enjoyed here by a hermit in centuries past. His hermitage of course is where we got the name of the village – many years ago it was simply ‘the hermitage of Handsacre’.

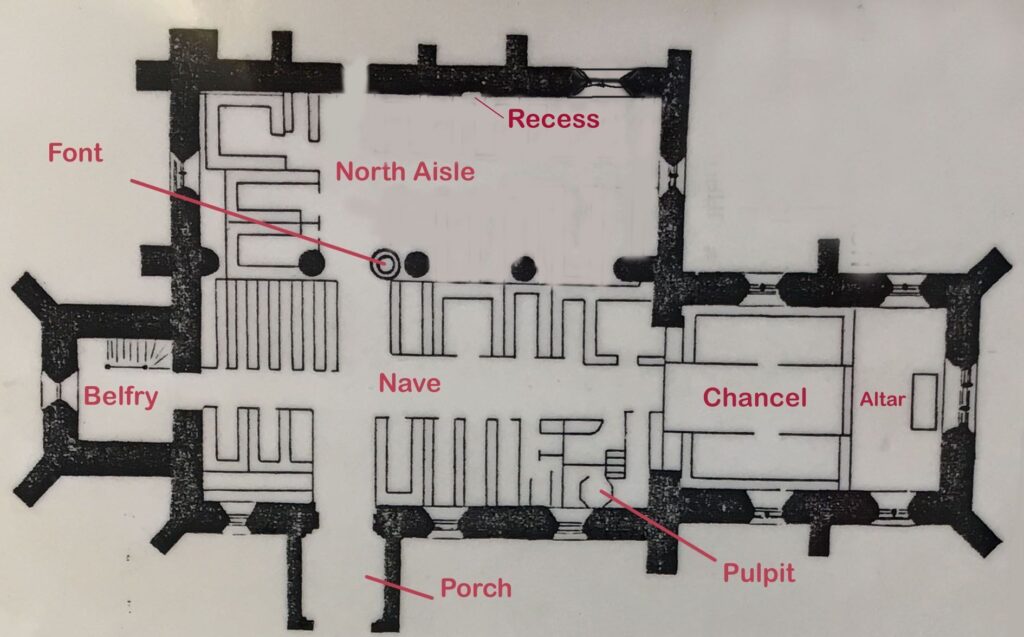

This church, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, has stood the test of time, though it now bears a somewhat battered appearance both inside and out. It’s picturesque though and a cherished part of our landscape and daily life. We have a nave, a chancel, and a north aisle, all roofed with tiles, along with a large southern porch and a steeple, both of which are relatively modern additions.

As we approach the porch which was built over 90 years ago now you can see the high-pointed arch entrance and the sundial sitting above it. Inside – mind your feet as we go down a step into the porch – there are stone benches on both sides, offering a place to rest out of the wind and rain. The door surrounds are a masterpiece of ancient craftsmanship and quite possibly Saxon in origin. It’s over eight feet tall and as you can see it’s richly decorated with twisted and indented pillars, zig-zag mouldings, and grotesque animal heads. Quite a feast for the eyes. Look closely at the arch’s crown, and you’ll see a rudely carved relief of a ram or holy lamb. Just imagine the skill it must have taken to carve these intricate patterns on the porch doorway.

Notice too, the recess carved out of the right-hand pillar—probably created to house a vessel for holy water so that the congregation could dip their fingers in the water before making the sign of the cross. We don’t do that now of course. I wonder how many hands have dipped into that holy water recess over the years, each carrying their own hopes and prayers? You’ll also see inside that there is still some plaster on the wall from where they had their images. No doubt we’ll remove it all eventually. Mind your feet again – another two steps down into the church.

This is the nave, it’s forty-one feet long and twenty-three feet wide. It’s quite a functional structure but there are some fascinating details. There are three windows, two to the east and one to the west of the porch. Numerous repairs to both the windows and the South wall have been made over time, as we cope with the effects of time and the weather. Look to our right and there’s the pulpit, near the uppermost south window, with the inscription: “The gift of George Licet and his wife.” George’s name also appears on our old oak parish chest, carved with “George Lysat gave this 1641.” His home, I suspect, was the modest house in Handsacre marked with the initials “G.D.L. 1615.”

Mind the step down into the centre of the nave – the church is quite a bit lower than the graveyard now – and over to our left is the square belfry which also serves as a vestry. It stands about forty-three feet high and it’s weathered oak shingles and weathercock crown it quite elegantly. High on its south side, the names of former churchwardens—Thomas Ames and Robert Swanne, from 1632—are inscribed, and on the West side is the name Thomas Trubshaw who was the stonemason who actually built the tower. Inside the tower, our three bells await their summons. Each bears an inscription, including the poignant: “I to the church the living call, and to the grave do summon all, 1727.”

I think that at one point the whole floor was covered with flagstones and there’s still quite a few around and there’s one very nice but lonely alabaster slab over near the belfry. Large parts of the floor now are just plain tiles but there are a few old glazed or even painted tiles in amongst them. A few of them are a bit damaged but its not worth repairing just a few – we wait until there’s a load to be done.

The font is a particular treasure, standing over by that central pillar between the nave and the north aisle. It’s over 700 years old, its basin is lined with lead and around the sides are 14 human figures in pairs under seven arches. Just have a look at how grotesque they are with their protruding eyes. I’ll wager you’ve never seen a font quite like this one—aren’t those eyes a bit unsettling?” I wonder how many thousands of babies have been baptised in this very font.

Most of the pews are modern now but you can also see benches with charmingly low backs, a testament to earlier times. It’s not that long ago that the Handsacre family had their pew in the chancel itself until an exchange was made so that now we, as churchwardens, have to look after the upkeep of the North aisle as well as the rest of the church.

Let’s move over to the north aisle, separated from the nave here by four round arches supported by five robust, round pillars. Above the central pillar, near the font, you’ll notice two carved human heads—one bare, the other with a reticulated headdress.

Right in front of us is the North door which I believe was put in for the Rugeley family from Hawkesyard although there’s no-one living in that sad old ruin now. We’ll see some more of the Rugeley family when we move over to the chancel. It’s a shame that this door is directly across from the main door because it gets pretty chilly in the winter when the North wind is blowing straight across the nave. No wonder we all huddle near the pulpit!

Just halfway along the wall here you can see this arched recess only about four feet high with a carved head as a sort of keystone. This is believed to have been the place where a stone coffin rested but we don’t know whether it was for one of the Lords of the Manor of Handsacre or maybe for one of the Rugeley family like Richard Rugeley who was buried in the church in 1623.. There’s no sign of the coffin now and no-one knows where it went. By the pews over on the west side at the back there are some items which I believe may have originally hung up as a trophy over the grave, and are now the only memorials left of the funeral of Richard Rugeley Esq. solemnized here with heraldic pomp on 23rd September 1623. There’s an esquire’s iron helmet – pretty battered now – on which some of the gilding remains, and the crest of Rugeley carved in wood and painted – a tower in flames, transfixed with arrows

The north aisle itself is the same width as the nave of course but only fifteen feet wide, with three small square windows letting in light. The east window was where the Handsacre family had their religious objects and no doubt an altar for their private prayers and that stone bracket there to the left probably had an image on at the time. You can still see the remnants of their intricate Gothic painted glass. There’s the outline in black and yellow with just the remains now of the canopy work with very narrow red borders along with those bright green and yellow quarter-foils. And all neatly put together with narrow strips of lead.

Just at the side of the wall here between the uppermost pillar and the East wall are three steps leading upwards above the chancel and you can just see a low round arch on the wall. I have no doubt that this was a staircase leading up to a room above the chancel – you can see traces along the chancel wall where there was clearly a room of some sort. This may have been the very sleeping place of the hermit!

Walking into the chancel now we first find this gravestone to Edward Westcote who used to live at Handsacre Hall. You can still read the inscription which is filled with pitch – “Here lyeth the body of Edward Westcott, Esq., late of Hansacre, who departed this life the twenty-ninth day May in the year of our Lord God 1681. Memento mori.” And underneath the writing are two bones across each other.

In front of us you can see the three-lighted Eastern window in front and on the right- and left-hand walls are two windows each. Over on the South side there you can see that we have now blocked up the old little round arched door that led straight into the graveyard. Most of the window glass has been replaced with plain glass but in a few areas you can still see the original painted glass. Up at the top of the main Eastern window behind the altar you can make out remnants of angels with censers. This far one over here on the North wall has the initials I.H.S. and the next window has the letters I and P with coronets placed around in a border.

Over there in the lower part is the letter M crowned – the initial letter of the Virgin Mary – but you can see that the letter M is formed from the two letters S and R joined together. Probably for the initials of Simon Rugeley. And the same M is on the far one in the South wall as well.

Just before we get to the altar rails there’s another gravestone in the floor and this one is marble but with no name on it. At one time it had four small shields of brass in the corners but there’s one missing now. Maybe at some time we will be able to find out what the remaining shields signify.

And finally, just within the altar rails, is another gravestone. This one is alabaster and it shows that one of the sons of the Offley family of Lea Hall was buried here in 1653 and that he only lived for six weeks. There may be other Offley’s buried here but this is the only gravestone.

Thank you for visiting our church today. It’s not only a house of worship but a living history book, telling the story of our parish, its people, and the enduring faith that binds us together. And if you’re around on Sunday please come to the morning service and you will get the chance to hear our new bassoon together with the other brass instruments. Who knows? Perhaps one day, this little church will have an organ, filling these ancient walls with music worthy of their majesty.

A fascinating tour of the church.

Such an interesting lively tour around the parish church. I believe the existing organ has an interesting history. Sounds from the organ filling the the place gives me the sense of continuous worship of God connecting us to Saxon times.