Early Life

Derek Spencer was the youngest of three children born to Richard Spencer, Manager of the Tailoring Department at the Co-Op in Rugeley, and his wife Ethel. The family lived at Sandy Lane, Rugeley. His eldest brother, James Ronald (Ron), was five years older, while Richard Archer (Dick) was three years older than Derek.

In the 1930s, the Spencers were one of the few families in the area to own a car. Summer holidays meant long drives to either Blackpool or Rhyl, often along quiet country roads with barely another vehicle in sight. On one trip to Rhyl, travelling via Woore, Nantwich, and Chester, they had a rare encounter — a collision with a motorbike at a junction. Fortunately, no one was hurt, although the car’s front wheels were badly bent. Derek remembered his father and the motorcyclist simply straightening the wheels by hand before continuing their journey. (At that time, the car only had brakes on the rear wheels!)

Occasionally, the family travelled by train instead. Christmas shopping trips to John Lewis in Birmingham became a tradition, often meeting up with uncles and aunts at Birmingham New Street station.

All three brothers attended Rugeley Secondary Modern School — not known as Aelfgar School until the mid-1950s. Derek went to school with Reg Hodson, and met Sam Scragg there, who later became a neighbour at Pike Lane in Armitage. Another schoolmate was Jim Vickerstaff, who also later moved to Armitage and worked at the potbank. Reg Hodson left school as soon as he turned 14 in September 1939, but Derek, with a December birthday, had to stay on a few months longer.

His first job was as an office boy at Edward Johns & Co (later known as Armitage Ware, and then Armitage Shanks). Derek soon found that office work wasn’t to his liking, and after eight months he was sacked. Still on probation and not yet a permanent employee, the company was careful: under the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, if he had been drafted into military service, they would have been required to re-employ him after the war. His replacement, Derek Bannister, was also sacked after eight months for the same reason.

Home Front

Derek was only 13 when the war started, so he paid little attention to rationing at the time. Later, he remembered that sweets were among the last items to come off rationing — not until 1953. Bread was always available, but in 1942, the very light, fluffy white bread was banned and replaced with a darker, heavier loaf known as the National Loaf. Made from a brown flour extracted at a higher rate (around 85% compared to 70% for white flour), it was grey, crumbly, and widely unpopular — but it was more nutritious and filling. Derek’s somewhat limited memory of rationing may also have been helped by the fact that his brother Dick worked for Harry Dean, the local butcher!

Derek’s first real contact with the war came during the evacuation from Dunkirk. In Rugeley one day, a lorry rumbled past, and George “Silver” Ball shouted out to him to run home and tell his mother that he was safe and being taken to the camp at Flaxley Green.

After Dunkirk, German planes began flying over Rugeley more frequently, usually en route to industrial targets. The town’s first direct attack came on 8 August 1940, when a German bomber dropped a land mine (more properly known as a parachute mine) near the Yorkshireman pub on Trent Valley Road — likely aiming for the nearby railway. Originally designed for naval use, these mines were dropped with parachutes to ensure they detonated above ground for maximum blast effect. The explosion shattered most of the windows along Rugeley’s main street.

Although the Spencer family obeyed the blackout regulations, they never went to the air-raid shelter when the sirens sounded. Derek recalled one evening in particular. After a visit to the White Horse pub on Brook Street, the family were back home having supper when they heard the distinctive, de-synchronised engine of a German plane. The first bomb landed far away. The second was closer. The third, they were sure, had landed right outside their front door. Everyone dived under the kitchen table.

This was 22 October 1940, when a stick of bombs hit Brereton. One bomb struck wasteland behind the Castle pub, demolishing a conservatory and slightly damaging St Michael’s Church. Fortunately, the bomb itself disintegrated rather than fully exploding. Another bomb from that night failed to detonate and wasn’t discovered until builders began work on Rugeley Power Station years later. It was eventually removed and safely detonated in the nearby forestry.

The last reported air attack on Rugeley came later in 1940. By then, Derek was no longer working at the potbank; instead, he was helping Harry Dean by delivering meat by bicycle while his brother was ill. While out on his rounds, Derek heard the rat-a-tat of a machine gun. Some of his friends, attending a funeral at the chapel, saw the German plane — a Messerschmitt Bf 110 — swoop and fire. Fortunately, there was little damage: just a few bullet holes in Whieldon’s bus workshop and the Green Bus Café near Rugeley Secondary Modern.

Although too young to mix much with the American troops billeted near Rugeley, Derek noticed something that struck him even then: black American soldiers were not allowed out of the barracks on the same nights as their white counterparts. Local people, however, welcomed both groups without distinction.

There was no shortage of local camps and entertainment. Bellamour Hall was home to a military unit where a young Harry Secombe — later famous as a Goon Show comedian — sang and helped organise shows for the troops.

War Service

After leaving the potbank he went to work for Rugeley Gas Co. Working for them meant that Derek was exempt from military call-up until the age of 20, but at 17 he volunteered, along with three others. Having been a cadet, he already knew the basics of drill, map reading, and signalling. He hoped to join the Navy — but his mother refused to give permission — so he enlisted in the RAF instead.

Derek’s first posting was RAF Cardington, a major reception and processing centre for new recruits. After eight weeks of basic training, he was sent to Blackpool for wireless operator training. In Blackpool, recruits were billeted in civilian digs, taking breakfast, dinner, and tea there. Each morning, a hundred men would fall in along a side street before being marched off to training.

One day, while waiting in line, Derek’s name — along with three others — was called out. He was told that he had “volunteered” for the Navy. In reality, he had been effectively press-ganged into the Royal Navy, a not uncommon occurrence at the time. His next posting was the Isle of Man for further wireless training, but he became ill, and finished his training in early 1945 at Plymouth instead.

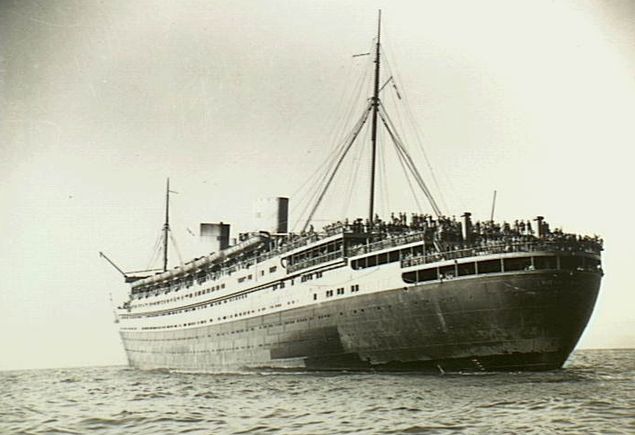

After two months in Plymouth, 200 men were gathered in the drill shed, and names were read out for demobilisation. When the list ended, six men were left standing — Derek among them. His records had gone missing. Two days later, he was summoned to the drafting office and told he was being shipped to Australia. Sailing through the Red Sea, Derek was onboard the New Amsterdam, a cruise liner converted into a troop ship, when the King announced on the radio that Victory in Europe (VE) Day had been declared. To celebrate, everyone was issued a tot of rum — the traditional “splicing the mainbrace.”

From Sydney, Derek was sent north to Manus Island in Northern Papua New Guinea. He was stationed there in August 1945 when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Following Japan’s surrender, Manus Island station closed down, and Derek returned to Sydney, enjoying five months of relatively easy duty in a comfortable barracks and making friends with the locals.

In June 1946, he returned to the UK and was granted foreign service leave, and then spent his final months of service at the naval air station at Yeovilton.

Derek’s two elder brothers also served during the war. Ron joined the RAF and spent most of his time as an instructor in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Dick joined the Army, where he represented his regiment in boxing, became a wireless instructor, and was stationed at Barnard Castle with the Tank Corps — where he met his future wife, a former Tiller Girl.

While their father had endured the horrors of trench warfare in the Scottish Rifles during the First World War, Derek and his brothers could look back and say they had all had, as Derek put it, “a good war.”

Back to Civvy Life

Although there was no obligation for Rugeley Gas to re-employ Derek after his military service—he had volunteered rather than been conscripted—they offered him a job without hesitation. He was trained to ride a motorbike and sent out as a meter collector, a job that, while routine, was vital.

At that time, most domestic gas meters were coin-operated. People inserted shillings—“putting a bob in the meter”—to pay for gas as they needed it. Derek’s job was to visit homes regularly, empty the coin boxes, read the meters, and return to the office with both cash and data. It was a role that demanded honesty, reliability, and a certain tact, as he was trusted to enter homes and carry money on his rounds.

Meeting Beryl and Building a Career

Derek’s early prejudice against ginger-haired children melted away when he met Beryl Foster at the gas company offices. Beryl’s widowed mother had remarried in the Potteries, and her stepfather, Jim Drinkwater, had taken a job at Edward Johns & Co in Armitage. The family settled at 1 Ricardia Terrace—later renumbered 2 Rectory Lane.

Derek soon trained as a gas fitter, a role that became increasingly significant as gas appliances entered more homes. Among the more innovative items he worked with were gas-powered fridges, which were sold by the gas companies in competition with electric models. With electricity supply still patchy in many parts of the country, gas fridges were marketed as a practical alternative.

They did, however, come with teething problems. Just after the war there were only five or six gas fridges in the Rugeley area, and Derek was often called upon to fix them. The usual remedy was surprisingly simple: switch off the fridge, tip it upside down, relight it, and then wait two or three hours to see if it restarted properly. When the prefabs were built on Upper Lodge Road in 1947, all were fitted with gas fridges. In 1955, he laid the gas pipes for the new houses on Millmoor Avenue.

Home Life and Family

Derek and Beryl became engaged, and he fondly recalls an evening out in the late 1940s with her stepfather, Jim Drinkwater, and a friend, Bill Martin. At the Crown in Handsacre, they ordered three pints of bitter, but the landlord would only serve them three halves—so they promptly left and headed for the Goats Head in Abbots Bromley, where they finally got the full pints they were after.

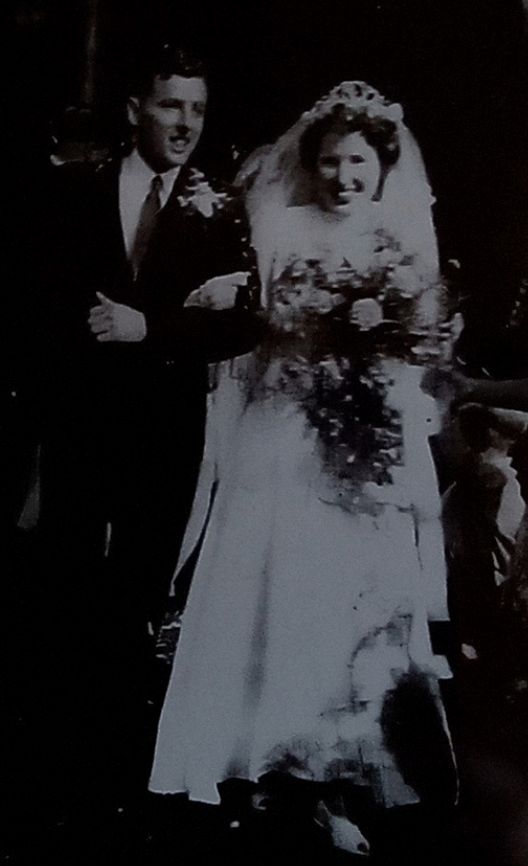

The couple married on 29 September 1951 at Armitage Congregational Chapel. They had originally hoped to wed at St John the Baptist Church, but the date was already taken. After the wedding, they lived with Beryl’s parents at Ricardia Terrace, a house owned at the time by Edward Johns & Co.

The company later decided to sell all its housing stock on Greenfields Avenue, Itonia Terrace (on Rugeley Road), Ricardia Terrace, and Volcania Terrace. Sitting tenants were offered first refusal, but Beryl’s parents declined—so Derek stepped in and bought the house himself.

Ricardia Terrace had been built in 1907 by Masons of Rugeley. The company charged £60 per house for Ricardia and £40 each for those in Volcania Terrace. Edward Johns & Co had supplied the plans and materials and even mixed the lime mortar, which had coal ash added from the kilns. This created Black Mortar, a very dark mortar—lighter and cheaper than lime mortar, but more porous. Derek paid £350 for the house. With a 15-year mortgage, his weekly repayment was 19 shillings—only two shillings more than the rent had been.

Theirs was only the second family on the street to own a car (after the Bensons of The Towers), and Derek built a garage in the back garden to house it. Behind the terrace lay a field owned by the pottery and rented to a local farmer, Follows Smith, for grazing sheep—though the fencing was poor and the sheep were frequent escapees. As the family grew, Beryl’s parents moved to Pike Lane to make space for the children: Hilary, Pamela, and Roger.

Returning to the Pottery

In 1959, Derek returned to the pottery, this time to work in the fittings department assembling cisterns. He later took charge of the stores. Factory life was structured by the daily sounding of the hooters, marking start and stop times: 8:00 a.m., 12:30 p.m., 1:30 p.m., and 5:00 p.m. At finishing time, the roads filled with crowds of workers heading home. Wages were paid in cash, and the local Barclays bank (on the site now occupied by the British Legion) was always busy at lunchtime, as staff queued to deposit wages, pay bills, or cash cheques.

Staffing levels in both fittings and stores were low, so Derek consistently worked an hour longer at each end of the day. The overtime provided a welcome financial boost for the family.

The Bungalow and Later Career

In 1967, builder Jack Hudson put The Hollies up for sale at £6,700—a price Derek and Beryl felt was too steep. Two years later, Jack’s son Arthur reduced the price to £4,500. When Derek went to discuss it, he noticed pegs laid out in part of the garden—Arthur explained he was selling off a building plot. Beryl suggested they build a bungalow there instead.

They bought the land and Arthur erected the shell of the building. Derek did the majority of the remaining work himself, hiring contractors only for the roof and electrics. In 1985, he added an extension, this time doing all the work on his own.

Once the children were older, Beryl returned to work. Lucy Morecroft had worked in the canteen at Edward Johns, and when she became cook at Croft Primary School, Beryl became her assistant. When Hayes Meadow School opened in January 1968, Beryl moved there as the cook in charge.

Derek, meanwhile, became a Customer Service Engineer, travelling across the country to solve technical issues. He remained in the role until his retirement in 1990, clocking up over 25 years with the pottery. Beryl often accompanied him on trips, particularly if the destination was of interest.

Retirement and Legacy

In retirement, the couple travelled extensively. They spent weeks in Australia reconnecting with friends Derek had made during his wartime service. They also explored Canada and the United States. As the years went on, their adventures narrowed to Europe and later to coach holidays around the UK.

Derek continued to play golf well into his 90s—only putting down his clubs the day before his 92nd birthday in 2017.

Beryl passed away in June 2013. Today, Derek remains surrounded by a large and loving family, with three children, seven grandchildren, and eleven great-grandchildren. Sharp-witted and engaging, he remains “bright as a button”—a pleasure to listen to and a living link to the rapidly changing world of postwar Britain and village life in Armitage.

What an amazing story to read of an amazing man who I have known all of my life, and who’s son and daughter in law are my best friends, Derek and Beryl have a wonderful family and im so lucky to be part of their lives.

Many thanks for sharing this beautiful story