By Ann Evans nee Morecroft

Armitage was already a large village in 1666 with 52 houses liable for Hearth Tax, the largest being Hawkesyard Hall and Handsacre Hall. By 1801 the population of Armitage and Handsacre had risen further to 464, then to 1,318 in 1901.

Samuel Morecroft, the second son of Samuel Morecroft and Eliza Jane Green, was born into this village on 23 September 1850 and christened on 27 October in Armitage Church. Father Samuel was an agricultural labourer at the time. As there was no industry in the village then agriculture and rural trades were the main areas of employment and most working people were labourers or servants.

Samuel had an older brother, George, and two younger brothers, Henry and Adam and in 1857, a sister, Jane, was born.

Samuel and Eliza now had 5 children to bring up on an agricultural labourer’s wage which was only 8s a week in 1850. At that time the wage would also vary according to the season with much lower winter wages. It must have been a struggle because if Samuel was ill or the weather was bad he wouldn’t get any wages. Some labourers lived in estate cottages, but Samuel didn’t so he probably worked for more than one employer. That meant that Samuel’s money had to find rent as well as clothing and food for 6 people.

On 19 December 1857, father Samuel died from ‘apoplexy’ at the age of 34 years. This was a disaster for the family. George the oldest boy was 10 years old and Jane had only been born a few months preciously. With no money coming in Eliza would have found it impossible to pay the rent. Family legend has it that Eliza was forced into the workhouse in Lichfield. This absolved the village of the task of supporting a destitute family that had lost their breadwinner but the workhouse would have been a last resort for any family. The workhouse was punishing for family life. Children under the 2 stayed with their mother so Eliza would have kept Jane and possibly Adam with her but George, Samuel, even Henry, aged 4, would have been forced to live separately. For them life would have been hard. They would have done hard menial jobs in the workhouse all day, and slept and ate separated from their mother and younger siblings. You can imagine how this might have affected Eliza and her young sons.

Again according to family legend, the family did not stay long in the workhouse. Their extended family worked to get them out. This may explain why I could find no evidence for these events. Eliza’s family just disappears under the radar during this period.

Whatever happened after Samuel’s death, Eliza was back in Armitage in 1866, married to Daniel Carthy. Daniel was a basket maker. Having a craft gave Daniel more financial security than labouring. Although Daniel was not born in Staffordshire, he seemed to spend his childhood in Alrewas where basket making was a traditional industry. The willow was supplied from osier beds located between the river Trent and the canal.

Things improved for the family at this point. The children were now working. George was a brick maker working for his uncle Thomas Morecroft at the brickyard in the New Road. Henry and Samuel were apprenticed as basket makers to their step father, Daniel. Adam was a farm servant. The youngest, Jane, was living with her grandmother, also called Jane, in Handsacre.

Samuel remained a basket maker for about 10 years. At this time most villages had basket makers and it was a skilled job, recognised by the Basket Makers Livery Company established as long ago as 1569. The aim of this company was to formalise and protect the London basket trade so it is unlikely that small family concerns like Daniel’s bothered with formal apprenticeships.

Baskets of all shapes and sizes were made, from small hand baskets to large baskets for the nearby pottery industry. Furniture was also made – chair seats being the most common.

Expert workmen could make a variety of goods, such as work baskets of different descriptions, table-mats, and fruit baskets. A skilled man could earn three or four shillings a day even when making coarser articles. Samuel in later years actually owned some osier beds on a small island in the River Trent. Osiers thrive in moist places so this was an ideal place for it. Owners generally let their willow-beds out to people who would cut them at certain times, then prepare them and sell them on to basket makers. So, in May every year Samuel would wade out to his island to cut and collect the osiers ready to sell on.

On 1 July 1871 Samuel married Ann Slater (nee Tomlinson) in All Saints Church, Kings Bromley, Staffordshire. He gave his father’s occupation as a land drainer, even though he had been dead since 1857!

Samuel was aged 20 and Ann was aged 31 when they married in Kings Bromley Church. This big age gap but not unusual at the time. Ann was a widow as she had been married previously to Edwin Slater in 1866. There were no children from her short marriage to Edwin.

Soon after their marriage the couple moved to Hednesford and in 1873 their first daughter, Sarah Ann was born. A son, Samuel Arthur, was born in 1874, followed by Thomas Edwin, in 1877 and Hannah Elizabeth in 1879.

They lived in the Hednesford/Cannock area for a few years but in the census taken on 3 April 1881, the family was back in Armitage. Samuel was now aged 30 and a carpenter. By the time of the 1891 census Samuel and his family was living in Handsacre with his family, still a carpenter and joiner.

Samuel’s wife Ann died on 20 March 1896. She was 56 old and had been married to Samuel for 25 years. All 5 children, now adults, were still living at home. They seem to have been very helpful in what happened next because by1901 Samuel was the Sub Postmaster of Armitage as well as a Cycle Manufacturer and Undertaker, a big jump up the social and financial ladder. By the time of the 1911 census, he had also added motor agent to his businesses. Samuel continued to run these various enterprises, with the help of his family, right up until 1934, according to Kelley’s Staffordshire trade directories.

Samuel had applied to be postmaster about 1898 when the then current sub postmaster, a Mr. Knight, gave up the job. Kelly’s directory of 1912 states: ‘Armitage: post, money order and telegraph office. Sub post master Samuel Morecroft. Letters arrive from Rugeley at about 5:45 am and 2 pm; dispatched at 10:15am and 7pm. No Sunday delivery. The wall letterbox, Handsacre cleared at 10:10am and 6:55pm. Wall letterbox at National School cleared at 10:25am and 6pm.’

Telegrams were an important part of post office business at the time for conveying important family information such as illness and death as well as more minor social events such as “will arrive for tea at 3pm”! Whoever delivered the telegram had to wait for the recipient to read it to see if an answer was required. Telegrams were often “reply paid”. During the First World War they were a dreaded form of communication as they often brought news of injury or death. Whoever delivered it often knew what was in the message as they had received it over the wire. Not an easy job for them to deliver bad news. In small communities like Armitage the postmasters job was very hard as everyone knew what such telegrams usually meant.

Undertaking was a natural progression for Samuel from carpentry. Most undertakers at this time were also carpenters, joiners or even builders – skills that translated easily into coffin making.

“Undertaker” was used from medieval times for anyone ‘undertaking’ a task, for example a ‘builder undertaker’ built houses and other structures. By the 17th/18th century a ‘funeral undertaker’ was a term for someone who undertook to organise and deliver funerals, which gradually abbreviated to just “undertaker”. It seems to be the only job for which the term ‘undertaking’ survived. When the term “funeral director” came into use is not really known though it was probably in the mid-20th century.

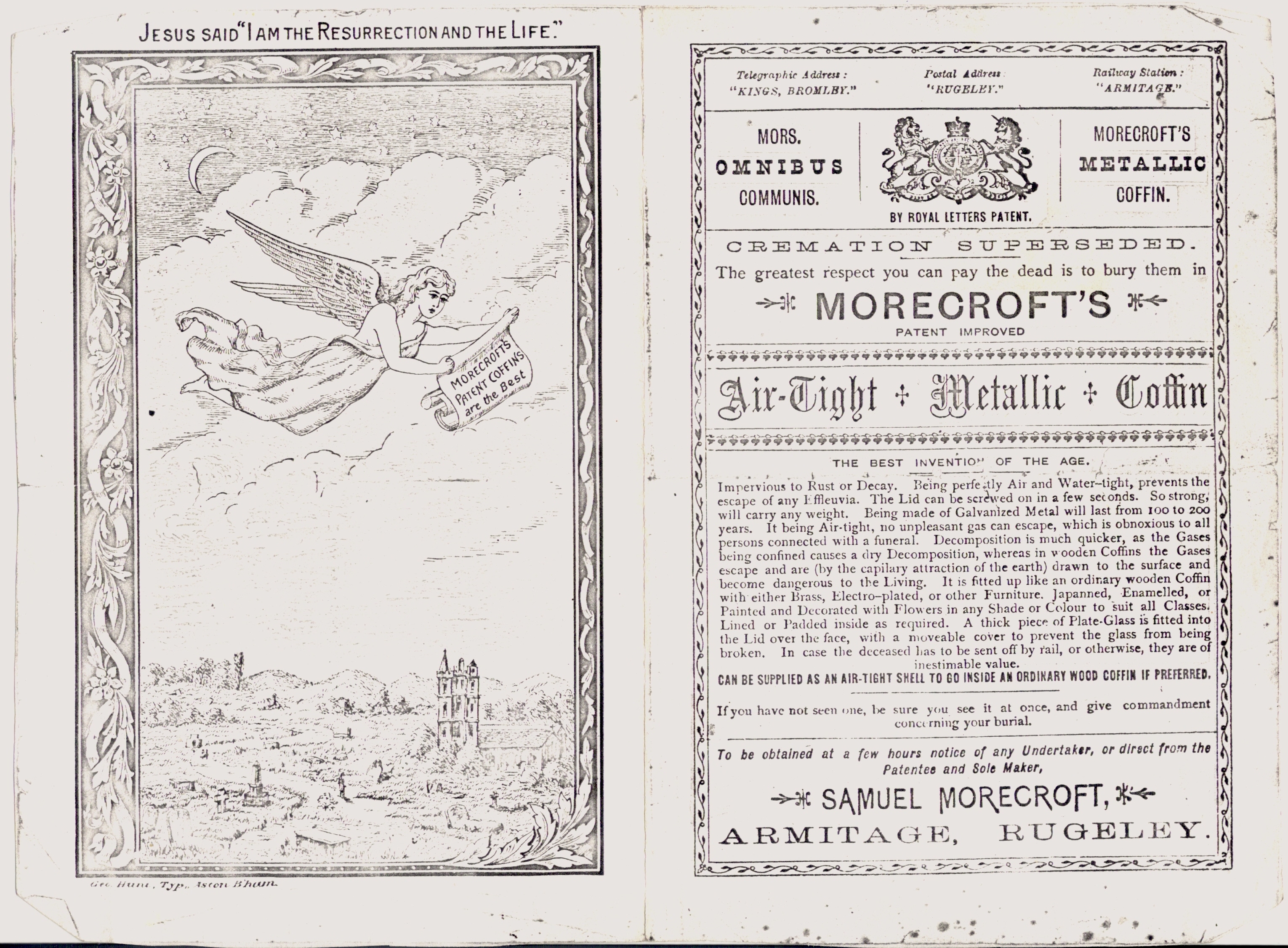

Samuel was always interested in new developments in all his enterprises. He even patented a metallic coffin. This advertisement claims “Morecroft’s metallic coffins “ to be the “ best invention of the age” !

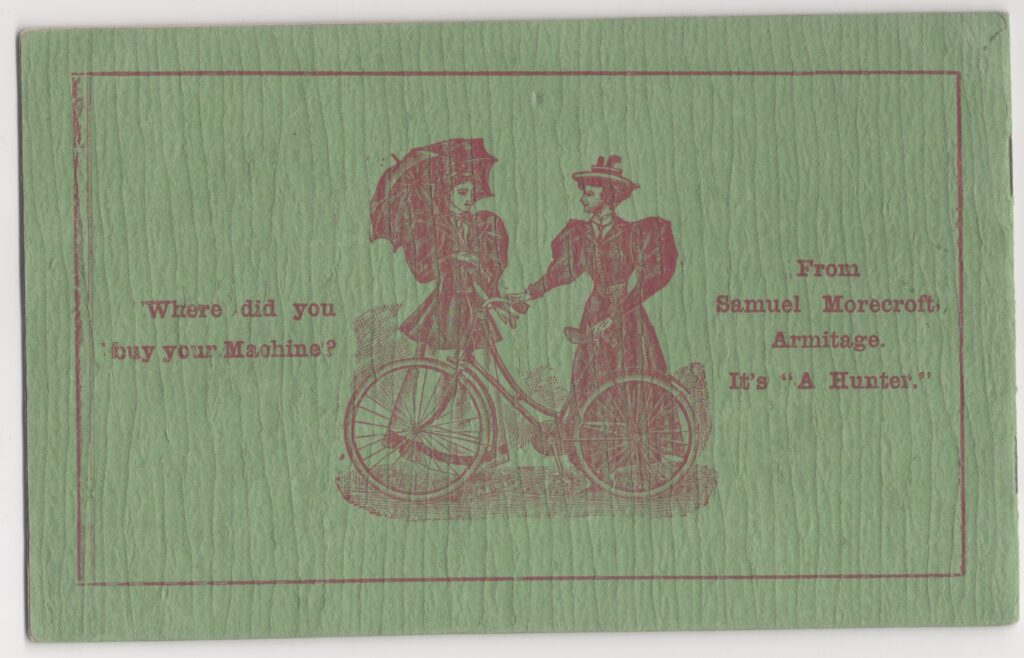

Samuel also took a keen interest in cycling which was becoming a popular and novel form of exercise. Samuel was a cycling pioneer and owned one of the first bicycles in the village. He soon added ‘cycle manufacturer’ to his list of businesses. He purchased frames and other parts from a factory in Birmingham and would cycle to the factory and cycle back to Armitage – a distance of about 20 miles – with the frames and parts slung round his chest and shoulders. He would then assemble the cycles in his garage and workshop in Armitage.

He built cycles for his family and the ladies of the family were some of the first ladies to ride in the village!

Samuel, a strict abstainer and non-smoker, took up cycle racing and became well known in the area. He would cycle in all conditions and continued to cycle right up to his death.

A man in the village had built a hut on a site in the New Road – roughly where the Post Office is today. They wanted to set up a YMCA but it didn’t really work. Local people, especially the Doctor, thought it might bring less reputable people into the village!

Samuel bought the hut and the land behind it for troupes of travelling actors who would use it for plays and shows. When these became less popular in the village he converted the hut into a butcher’s shop in the late 1930s which his grandson, Graham, ran for many years.

Samuel was not only a very practical man, good with his hands, when he built cycles or repaired motor cars, he was also a good manager. For example he acted as what might then be called a clerk of the works when his friend John Peate wanted to build a new house in the New Road in Armitage. He ordered in all the materials needed right down to the last nails and screws and engaged workmen to do the job.

This triggered an interest in building and he went on to build two bungalows on land behind the hut that he owned in the New Road, currently 73A and 73B New Road, Armitage. These bungalows were built back-to-back. One bungalow was conventionally built out of bricks but he used only concrete for the other which was then a novel material for house building. This bungalow also had two large stained glass bay windows.

This piece of land eventually housed a huge shed/store/garage, and a sty and field for pigs, as well as the 2 bungalows and butcher’s shop! The garage and workshop were used by Samuel’s son Edwin, to run a haulage and coal delivery business. Edwin and his family also lived in the new concrete bungalow. The garage/ shed was an old WW1 hut that Samuel bought from Penkridge camp after the war. He collected it on the back of his lorry and rebuilt it. Later he purchased, for £80, a piece of adjoining land which stretched down to the railway bridge. He split this up into sections and rented it out as allotments.

Another of Samuel’s interests was photography. He purchased a big camera and tripod and took photographs around the village, of the Church, the canal, the school, for example. He then developed them and had them made into postcards, to sell in the Post Office. In those days photographs were made on dry plate glass negatives, a technique that had been in use from the 1880s. Samuel used the same technique when he developed his photographs in the early part of the 20th century. It was an imprecise art as the negatives were developed by placing them in a window to catch the sun!

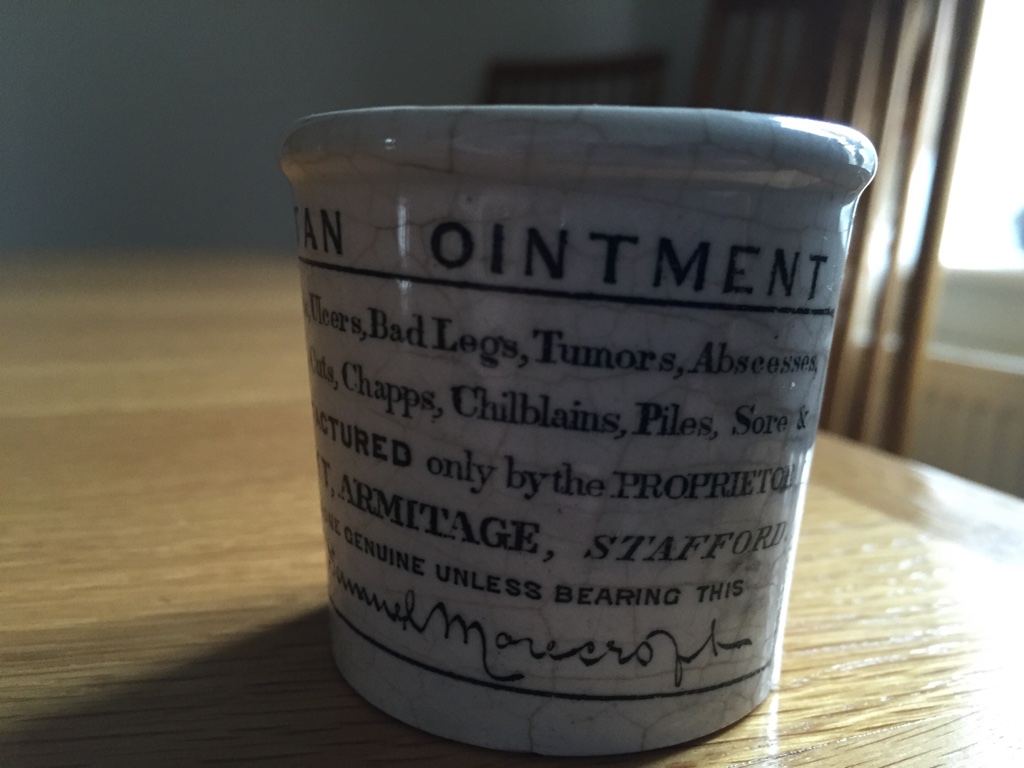

Another of Samuel’s interests was health. He was an early advocate of natural remedies and healthy life styles.

He made an herbal ointment called “The Good Samaritan”, a remedy for all sorts of cuts and grazes and illnesses! The ointment was sold in ceramic pots of two sizes, costing 9d and 1s/1d. Pills were also available. He collected herbs for the ointment from his garden and from specific places on Cannock Chase. He even made special mysterious trips once a year up to the Lytham St Anne’s area to collect a certain ingredient. Perhaps that ingredient was seaweed as the ointment was a very dark green colour!

The herbs would be dried by hanging them in bunches around the house until needed to make up new batches of ointment. He made the pills and ointment from about 1898 up to about 1930, and then for some reason he seemed to lose interest in it. He never told anyone the recipe and it died with him.

The family was the first to have a car in the village. His two sons would drive him and other relations around the area and take trips to Bournemouth, Manchester, Burton on Trent etc. They all wore big thick, warm coats because, although the cars were well looked after mechanically, passenger comfort was very basic!

Samuel was highly thought of in the village – a charming and helpful man who would give time and often money to those less fortunate. He was very active in village life being at various times a member of the Parish Council, Chairman of the School Managers, and involved with various charities in the village.

He was a vigorous man with determined views on how life should be lived and expected his family to abide by those rules too. He kept the family together and did not give any of them the opportunity to strike out on their own to any extent. They were all expected to work in the various family businesses. In fact, the Post Office and the Funeral business were continued by the family up to about 1980.

He was also a religious man. To begin with the family were Methodists, but for some reason Samuel fell out with them and so they became Congregationalists. He was a well-known local preacher. He gave generously to the chapel, in time and money.

Samuel was an excellent advertisement for his own pills and health regime, living a long as well as a full and active life. He died at The Post Office on 12 September 1934 just 10 days before his 84th birthday.

He was buried, in one of his own metallic coffins, on 15 September 1934 in Armitage churchyard, in the same plot as his wife Ann. He had been a widower for 38 years.

This is so interesting Ann. It fills in lots of gaps in my research about Samuel. Thank you.

A fascinating article. Well done!

I have had a pot which contained The Good Samaritan Ointment on my window shelf for ages, and today decided to look to see if anyone knew of him, and his pharmaceutical exploits. The biography of Samuel and his family is fascinating, and the salve, like many others of it’s ilk was Guaranteed to Cure most skin ills. Another product of which I was the owner for a short while was Grasshopper Ointment, again a dark green colour, but this was due to the Copper content…….famous as a Chilblain cure before central heating removed that problem !