Evensong, on Sunday 20th August 1837 and the church looked very different from how we know it today. There was no stone wall around the (very much smaller) churchyard. The main, (southern), doorway opened directly into the nave of the church, without the benefit of a porch, and not into the south aisle which wasn’t built until fifteen years later. Opposite the main door, in the north aisle, was another door which let in an icy blast in the winter. (This had been put in so that the Rugeley family could walk or ride straight from Hawksherd Hall which had been built pretty much where the power station towers used to be).

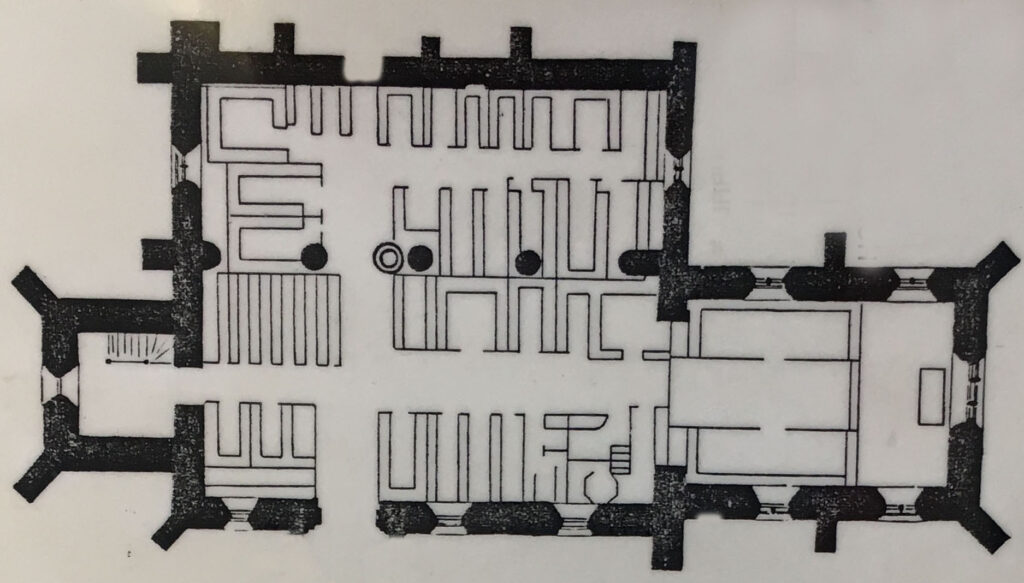

On the left as you came in through the main door was the belfry which also doubled as the vestry where the Reverends Wilson and Wetherall had prepared for the service. (The current vestry was built at the same time as the addition of the south aisle). The organ was on the west side of the north aisle whilst the font was near the centre pillar between the nave and north aisle. In the southeast corner of the nave is the pulpit.

Apart from the church tower which had been rebuilt by Thomas Trubshaw, a stonemason from Great Haywood, in 1632, the church was falling apart. The roof was crumbling, it leaked in numerous places, the mortar was falling out from between the stones and some of the windows whistled when the wind blew.

In places could be glimpsed fragments of the colourful murals of the Saints which used to cover the walls. The Reformation in 1534 had led to the creation of the Church of England and the murals had been whitewashed over when the Church of England decided that having images of the Saints was a violation of the Second Commandment ‘You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the LORD your God am a jealous God’. The whitewash was now flaking off in places. Stone brackets which in former times had held figures of the Saints were still there but empty.

Before the Reformation parishioners could stand, kneel, or even mill about the nave if they so chose. In order to emphasize that they were no longer Catholic, the Church removed all sorts of things from their services e.g. confessions, whilst sermons became longer and became full of ‘Thou shall nots…’ and fire and brimstone. By this time the Lords of the manor, (and after them the inhabitants of Handsacre Hall), had a box (or pew) in the chancel itself. In Dr. Johnson’s dictionary a pew is defined as an enclosed seat in a church and the Handsacre Hall pew would probably have had four walls – maybe up to shoulder height – together with curtains, kneelers, tables, and anything needed to make their attendance at church more comfortable and stop the lesser folk looking at them whilst they prayed.

The Handsacre Hall pew was moved out of the chancel and the longer sermons meant that more parishioners wanted to sit down. The Church officials sold or rented out rights to have a seat and of course the more prominent members of the community had to have a box pew. This photograph from St. Firmin’s church, North Crawley shows what the pews may have looked like.

This church plan shows the layout of the pews in 1837 and you can see that the pews are not lined up facing the chancel or the pulpit as they are today and some people would have been sitting with their backs to the preacher. They believed that hearing the Word of God was more important that just staring at a preacher. Towards the back of the nave were rows of old-fashioned benches with low backs – for the common folk.

Not only could you ‘buy’ pews in the church, but these became a saleable item which was attached to the house where you lived – it was not uncommon to see adverts for house sales which included the rights to pews in the church.

Seven years previously the Church Committee had agreed that the church urgently needed rebuilding, but they still hadn’t managed to raise the money, (and wouldn’t for another six or seven years).

That evening Mary Short, dressed in her Sunday best, was in her customary pew where she, and at least two previous generations of her family, had always sat. Looking over the shoulder-high sides of the pew she could see her friends and neighbours and the Rev Wetherall, clerk to Reverend Wilson. She saw George Emery enter the church. He stormed up to her pew, pushed open the box door and ordered her out of ‘his pew’.

She refused to budge and he shouted and swore at her then grabbed her round the waist and threw her onto the floor and kicked her towards the door. He dragged her, kicking and screaming, from the pew before members of the congregation and the ministers intervened. Emery shut the pew door and refused to come out. Friends rallied round her and she sat by them with the whole congregation aghast at what they had just witnessed. Eventually the service began.

The next day Mary went to the police and accused George Emery of assault and battery. He was a tenant farmer in Handsacre and had recently (1833) married his third wife who was less than half his age. When his daughter Elizabeth had been baptised in 1835 he had stated that his occupation was ‘Gentleman’.

The police quickly took witness statements and the case was heard on Saturday 26th August i.e. only six days after the offence, in the Grand Jury room, Shire Hall, in Stafford before four JPs – Charles Clarke Esq., (Chairman), Edward Monckton Esq., Thomas Hartshorne Esq. and R. Beech Esq..

Mary was first in the witness box. She made her statement and exhibited her arms to show the marks that she had received. On cross examination by a Mr. Passman for the defendant she admitted that the defendant had, at various times, laid a claim to the pew and about nine years previously had put a lock upon the door with a view to establishing his right of ownership. She stated that, far from acknowledging that right, she had uniformly continued to occupy it just as her family had since 1770 or even earlier.

The Rev. Wetherall was the next witness and he stated that Emery’s manner had been extremely violent and it was with great difficulty that he had been able to proceed with the service. He presented a letter which he had since received from Emery and said it contained the most violent and threatening language he had ever met with: unfortunately it formed no part of the case so was not received in evidence.

A Mr. Robert Taylor, a student at Oxford, was the next witness. He was spending a short time at Armitage and confirmed the stormy language and violent manner of Emery.

The Rev. Francis Wilson was the final witness for the prosecution, and he corroborated the other witnesses as to Emery’s manner.

Mr. Passman made his case for the defence by stating that there was in fact no case to adjudicate. Mr. Emery had, at various times, laid a claim to the pew as admitted by the complainant. A man is justified, he stated, not only in committing an assault, but a battery, in support of his right to a pew. Emery had repeatedly cautioned Mrs. Short against sitting in the pew, and his only alternative therefore was to eject her by force. As to the bruises that had been shown, Mr. Passman stated that ‘every one knew that the flesh of females was extremely delicate and soft, and soon changed colour, if more than ordinarily pressed by the stronger hands of the opposite sex’. He did not in fact deny the assault but attempted to justify it.

Mr. Hartshorne (JP) stated that Mr. Passman had presented no evidence that Emery had the right of possession. Indeed, from the evidence presented, the prima facie right was with Mrs. Short – she had occupied the pew for thirty years and it had been in their family for three generations.

Mr. Monckton (JP) perfectly agreed with the principle laid down by Mr. Passman – that a man was justified in protecting his right – but that right must be legally established before he resorted to the protective measures allowed by law. Otherwise, a man had only to fancy that he had a right to property and then proceed to take it by force.

Mr. Emery then stated that he had a right to the pew, and he would maintain that right if it cost him a thousand, or ten thousand, or even a hundred thousand pounds. He did not want money, and he “neither minded parsons nor clerks”.

After a short conference the Chairman stated that they were unanimously of the opinion that the assault had been proved. They were not there to judge whether Mr. Emery had the right to the pew. The question they had to decide was a very simple one – whether he had committed the assault alleged – and of that there was no doubt. The case before them had a singular aggravation; it had been committed in the House of God, when the peaceful inhabitants were assembled for Divine worship. The magistrates were equally unanimous in the amount of penalty which should be levied and they would therefore impose the maximum that they had the power of inflicting – £4 4s as a penalty and 16s costs – and Mr. Emery was ordered to pay the £5.

Emery had moved into the village in the mid 1820’s to become a tenant farmer in Handsacre and claimed that the right to the pew came with his house. Shortly after the assault he gave up the lease to his farm and moved back to Kings Bromley where he had lived some twenty years previously.

Mrs. Short continued to attend the church and, of course, always sat in her pew.