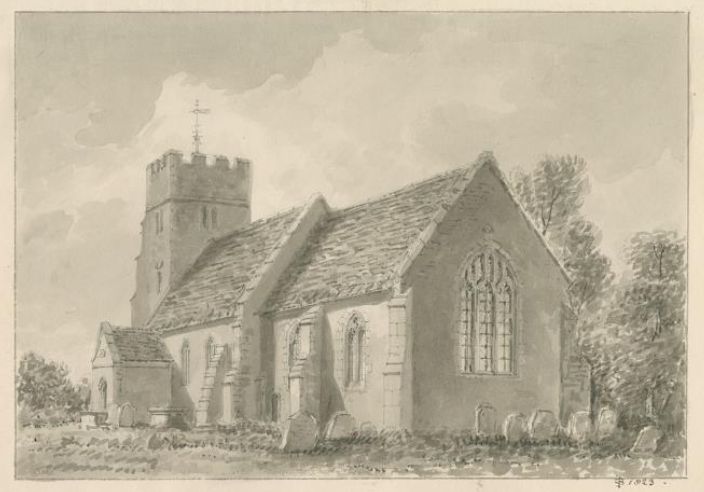

St. John the Baptist is believed to date from the early 1100s with the first element being the nave followed by the North aisle and the tower. The chancel was added a hundred or so years later. In 1630 the tower was in a danger of collapse and was rebuilt in 1632. By 1750 then large parts of the church were over 600 years old.

Early repairs (1750 to 1810)

As with any historic building, St. John the Baptist Church required constant maintenance, which increased with age. Churchwardens, responsible for the church’s upkeep, faced growing challenges. Surviving parish accounts from this period highlight regular repairs to masonry, windows, and roofing.

In 1752, significant repairs were undertaken. A new weathercock crowned the steeple, and over 4,000 tiles were used to restore the roof. Despite these efforts, maintenance remained relentless. By 1806, the century-old porch had collapsed, prompting William Gaunt to be paid 4s 6d to remove the remains. Recognizing the mounting challenges, a subscription was raised, securing nearly £170 through contributions from prominent local families like the Listers, Chadwicks, and Chetwynds.

The work, which spanned three years, involved extensive collaboration with local craftsmen. Thomas Bond provided 500 quarry tiles, while Samuel Glover of Bilston supplied over 3,000 roof tiles. Oak timbers supported the roof, complemented by ridge boards made from deal planks. Builders, bricklayers, and masons like Robert Bradbury worked tirelessly to restore the church’s structure. By the project’s end, the church boasted a new roof, a new Gothic door and a rebuilt stone porch—though the sundial was notably absent.

Transforming the church interior

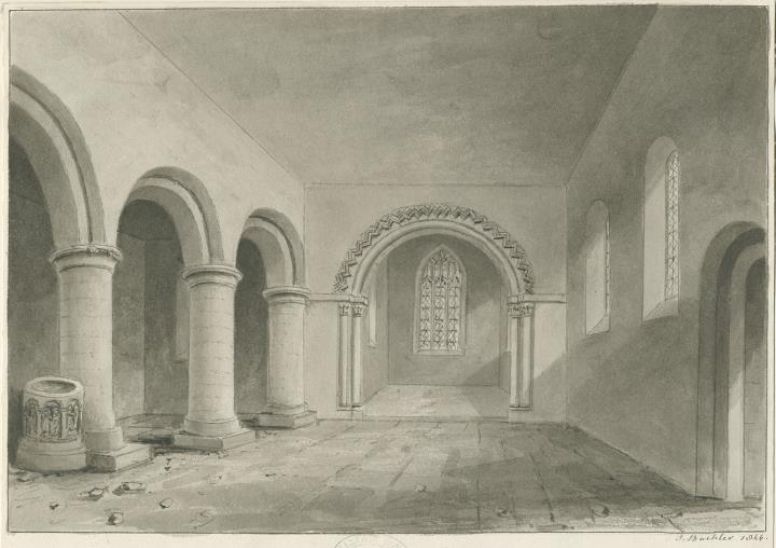

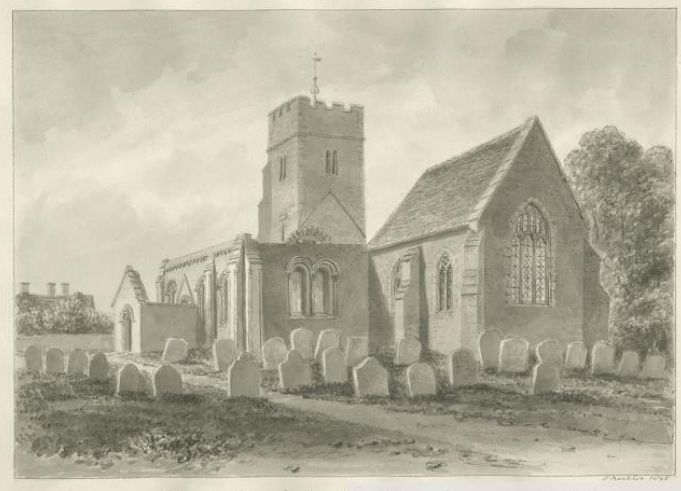

By 1818, less than a decade later, the church required further extensive repairs, prompting a more radical interior transformation. Alongside repairing the tower, its ground stage was converted into a vestry, and the entire church floor was refitted with quarry tiles. Key renovations included completely whitewashing the interior and painting the pillars to resemble stone—a major change in an era lit only by sunlight or candlelight. An even more dramatic modification was the addition of whitewashed false ceilings, each featuring a trapdoor for access. A set of stairs in the tower’s ground stage allowed entry. Part of this alteration included a singing loft, with a skylight installed in the roof to enhance illumination. This painting from 1844 shows the false ceiling in the nave.

Major reconstruction (1840s)

Most of this work related to the roof and none was done on the external walls and by 1830 the church was again in trouble and this time the church was described as being in a ruinous condition. The population of the village had doubled since the last major work had been done and it was also now too small for the congregation. In 1830 the Parish Council passed a resolution to ‘repair the church and stop up the North door’. This was clearly going to be a big project and work didn’t actually start for fourteen years.

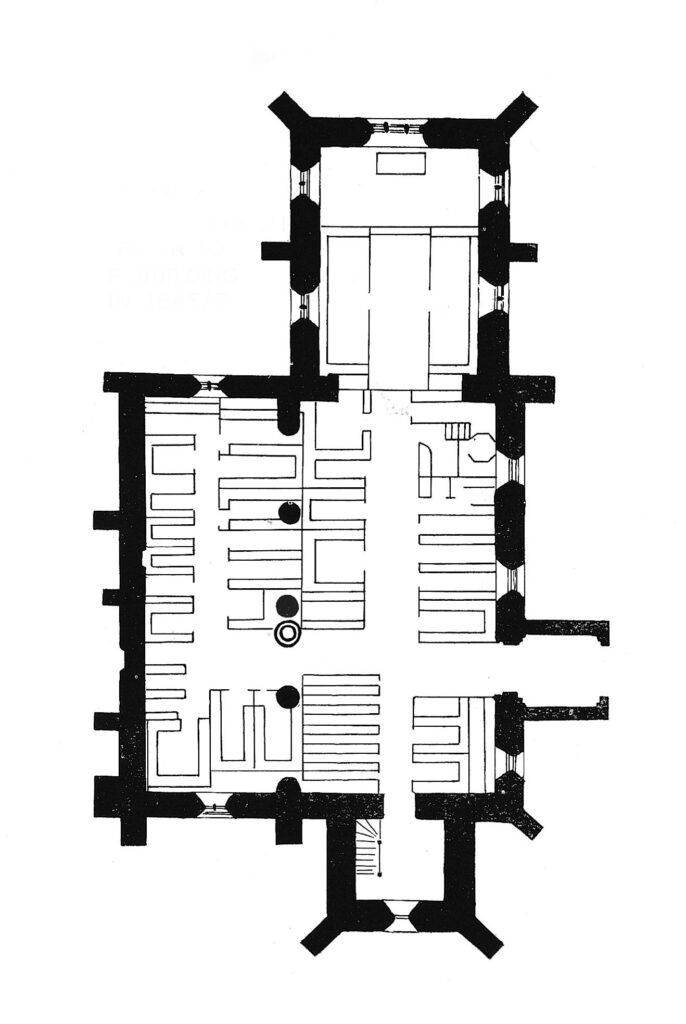

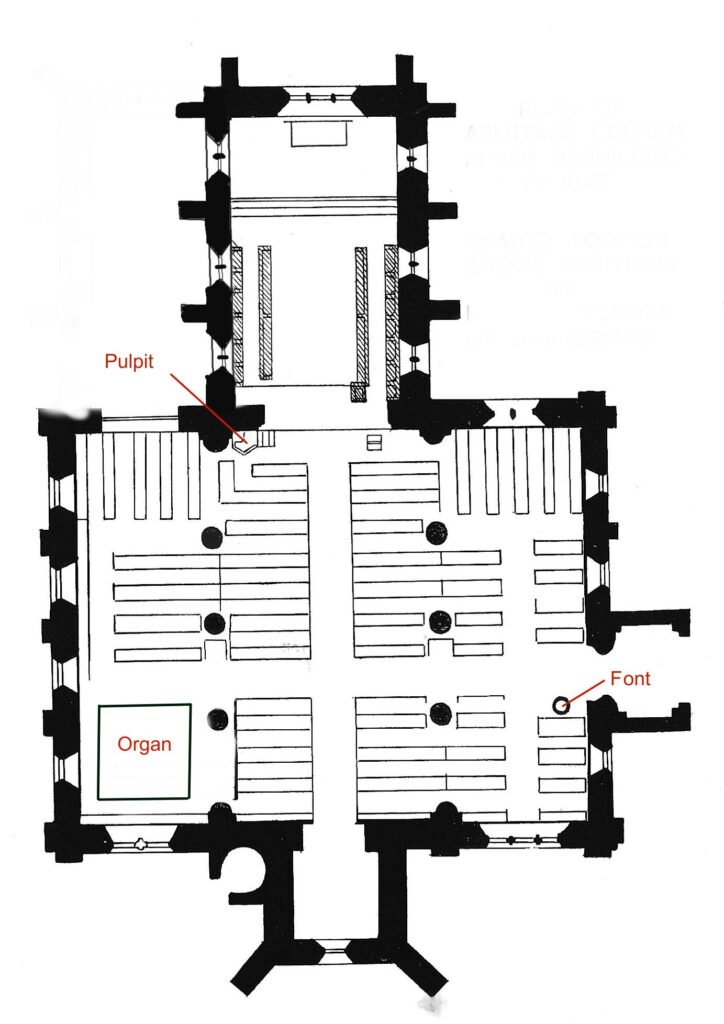

The rebuilding was designed by Mr. Ward of Stafford and the nave and the North aisle were to be rebuilt with a South aisle being added to increase the seating by 100 persons. As an interim measure a gallery was built in the nave with £14 provided by the Lichfield Diocesan Society.

The design for the church’s reconstruction sought to replicate its original format. The nave and North aisle were rebuilt in the Norman style, featuring thick cylindrical columns supporting heavy, rounded arches. However, the chancel again adopted the Gothic style, incorporating pointed arches. Not all elements were duplicated; for example, the original North aisle had a hipped roof. The tower underwent slight remodelling receiving a new arch between the nave and the tower, along with a replacement west window—a three-light design matching the style of the nave.

To fund the project, a subscription was organized, raising over £1,100 from more than 40 contributors. The largest donations came from Josiah Spode IV (£500), Josiah’s mother (£100), Mr. Thomas J. Birch (£100), and the Lichfield Diocesan Society (£100).

Demolition began in 1844 but soon encountered unexpected challenges. The chancel was found to be severely cracked, likely due to the removal of the nave, and required rebuilding. The main doorway also needed replacement, as the original stone carvings were deemed incompatible with the new masonry. Instead, these carvings were repurposed to create a graveyard cross.

The additional costs meant the original subscription was insufficient. By early 1845, churchwardens placed advertisements in the Staffordshire Advertiser to raise the estimated £500 shortfall, bringing the total projected cost to £1,620. The extra funds were eventually secured, with contributions from the Curzon, Chadwick, and Chetwynd families among others.

Despite the reconstruction, the church remained in use. Baptisms and burials continued, and, remarkably, weddings were still conducted—perhaps suggesting that the chancel was prioritized during the rebuild. By 1846, the church was fully reopened for all services.

Controversy and criticism

Not everyone supported the reconstruction efforts. In January 1845, a critic using the pseudonym “ZigZag” wrote a scathing letter to the Staffordshire Advertiser. ZigZag lamented the demolition of the chancel and the decision to create new carvings for the doorway. He was particularly incensed by the failure to reuse original elements of the church:

“The whole of the Norman portion levelled with the ground! Plunging into the ruins, I discovered, however, that the old capitals, mouldings, and other ornaments, carved eight centuries ago, were still lying about in all directions; and this gave me fresh hope. At least, I thought, they will replace every one of these glorious old zig-zags, catsheads, etc., etc.; and I applied to the head mason of the yard for a corroboration of my surmises. Let the head mason speak for himself in reply: ‘Lor, bless ‘ee, no, sir; them stoans be goin’ down to the Hall, to make a grotto on!’ What motive can be assigned for the demolition of the beautiful recessed arch of the chancel (in particular), I am utterly at a loss to imagine.”

The reference to “the Hall” almost certainly points to Hawkesyard and explains where Hawkesyard got the stones for its grotto.

Decades later, in 1871, another critic calling himself “Viator” voiced his displeasure in The Building News. He condemned the treatment of the south doorway:

“An objectionable case of mutilation came under my observation a short time ago. The parish church at Armitage has been rebuilt. Here was a fine Norman south doorway, the ornaments of which were extremely grotesque and singular. Instead of retaining the old doorway as such, they have imitated it, and some of the stones belonging to it have been stuck into an iron framework as a churchyard cross. The swelling of the metal by corrosion has done more damage to the carved work in a year or two than the weather and neglect in their old position did in six or seven centuries. When I saw them, they had all toppled over together and were split in all directions. I am of the opinion that the interests of architecture and archaeology would have been better served by the reconstruction of the original arch, even though defaced, than by the reproduction of the old in a new material.”

Josiah Spode also disliked the new churchyard cross made from the original doorway stones mentioned above and eventually commissioned a replacement. Additionally, the dual function of the tower as both bell tower and vestry proved less than ideal. To address this, Spode later funded the construction of a separate vestry and a larger organ for the church.

Another interesting article, Richard, thank you. I must admit that always having had a battle with that organ being where it is, at the front of the church and stuffed in almost as an afterthought, I do wonder why it wasn’t left where it was at the back of the church, where the sound would not have been deadened as it is by the wall between the organ and the rest of the church. The sound is great in the choir stalls, but not so good at the back of the church! It’s why I always played it so loudly!