Hunger was never very far away for the Victorian poor. Large numbers of them woke up famished and spent much of their lives in a state of semi-permanent wanting for food. In 1844, Frederick Engels, who wrote the Communist Manifesto with Karl Marx, described the diet of some English communities as consisting of small bits of bacon cut up with potatoes and amongst even poorer communities as ‘bread, cheese, porridge and potatoes’.

Enclosure had already removed most of their common grazing land and then potato blight arrived. Potatoes are rich in vitamin C and could provide more calories per acre than any other crop available to them. During the 1840s though the blight took a third of the potato crop, (and three quarters of it in 1846).

If you couldn’t get work, life was even tougher. By 1849 the pottery was shut. The pits were really struggling and there were no jobs down the pits for any miners in either Armitage or Handsacre. But you could always go foraging for wild fruit and roots, like your distant ancestors. Or go hunting for food, like your distant ancestors. Only they had brought in the hated Game Laws so now it was called poaching.

Gifford Weate lived in the Chetwynd Arms on the New Road, Armitage, where his dad worked as a shoemaker by day and beer-seller by night. On this night he waited until all the customers had gone, which didn’t take too long because everyone had got a bit joyous the night before for Guy Fawkes night, and made his way, through his sister’s bedroom, to the room he had shared with his dad since his mum had died a few years earlier. He picked up his gear for the night – his shotgun, cartridges, powder, bludgeon and of course his sack for the game. (No need for any nets tonight as they were going for pheasants)

If everyone turned up like they had promised the night before there would be about twenty of them or even more. There was a demand in Lichfield market for as many pheasants as they could get, never mind some of the local posh folk who would be quite happy to have a pheasant or two with no questions asked.

Walking down Old Road, the night was pretty cloudy, but the moon appeared from time to time. When he got to the ford, he saw Tommy Hiden and Jack Whitfield collecting stones. Being older than most of the rest who were going tonight as well as married they were anxious to make sure that everything went well. They would only need stones if they were unlucky enough to stumble into a couple of gamekeepers or even constables, but he also picked up a dozen or so that fitted nicely in the palm of his hand. He had never forgiven that Hampton who had tried to get him sent down a few years ago when he been found with a hare so a nice stone or two would be handy if they saw him. Before they had finished, they were joined by some of the others also looking to collect stones.

When they had collected enough, they carried on up the road and met Abe and Ike coming out of their houses. Another dozen or so were waiting over the canal bridge by the Crown. They bantered back and forth for a bit to give any stragglers a chance to join and then set off for the new bridge.

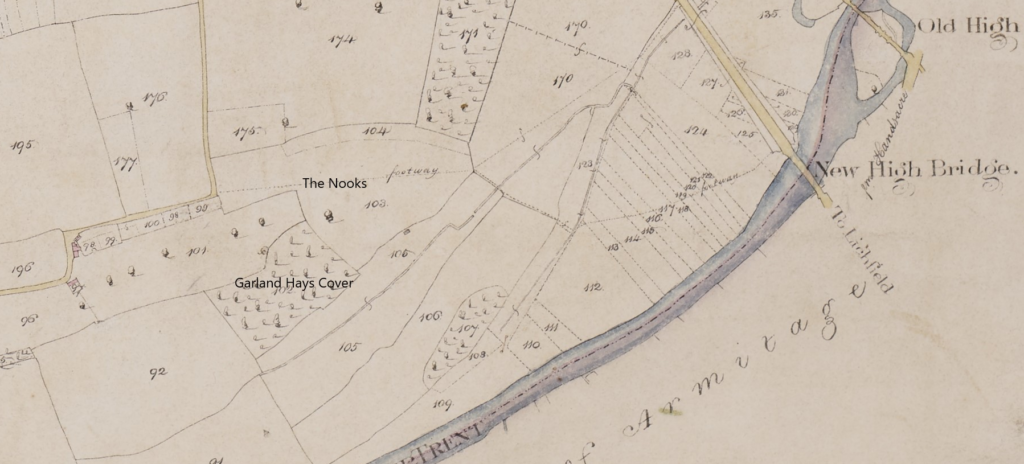

Their target tonight was Garland Hays Cover in Mavesyn Ridware so once they were over the bridge, they took the footpath through Alders Meadow and across the Pingle. As soon as they had climbed over the hedge into the Cover, Gifford found a couple of dummy pheasants fastened to branches in the bushes. Whether this meant a gamekeeper was around or not was a bit concerning so some of the lads went to each of the edges to keep a lookout. Everyone else scattered throughout the Cover looking for pheasants and before long he heard one shot, closely followed by two more. Another couple of shots rang out before he heard someone shout out that there were two or three busybodies trying to hide behind an animal shelter in the corner of The Nooks.

Abe and a few of the lads climbed the hedge and went towards them. The busybodies turned out to be the police – one of them was Crisp who was lodging with Dan Stubbs the baker down in Handsacre. Abe shouted at them and pointed his gun at them but they still came on so he shouted at the rest of us to pile in. They didn’t need much encouragement and they fanned out a bit and started throwing stones at them.

Someone ran past him and went straight towards Crisp and he recognised Hampton the gamekeeper and after that things got a bit hectic and stones were flying in every direction. ‘Watch who you’re throwing at,’ shouted someone. He managed to edge around behind the police and threw his bludgeon for better accuracy knocking one of them over. Before long the police had had enough and backed away from them down the path to the lane and then turned tail and ran. Hampton wasn’t quite as quick, and someone managed to get him really good with a stone just as he got to the lane and down he went. Hampton managed to get up and scrambled after the police out of sight down the lane.

No-one had picked up the pheasants so they went back into the Covert and hunted around for the bodies and then decided that it would be better if everyone went back home and kept their heads down.

Like everyone else who had been out Gifford was a little tense the next day or so but gradually relaxed when no police turned up looking for any of the group. Perhaps there had been enough cloud to make it difficult to be confident of exactly who had been out.

James Hampton was Squire Spode’s gamekeeper and took his job very seriously which was why he was over in Mavesyn Ridware on the night of 6th November watching the coverts. He had walked past his old place, the Keepers Cottage, where he had lived until a couple of years ago, and had a look round the Keeper’s Plantation then, at about 11pm, he met Ellis Crisp, who was a Sub-Inspector of Police, and lodged in Handsacre.

The police had clearly got wind of something because Crisp told him that Inspector Turrall and a constable called Feaveryear would be meeting up with them soon. By the time they had all met it was getting on for 3pm and they headed for Garland Hays Cover which was the supposed target for a gang of poachers.

As they got to The Nooks just off the lane, they heard a shot in the Cover and they all crouched down by an animal shelter. He waited until the moon went behind some clouds and set off to go round to the far side of the cover – the police stayed hidden behind the shelter.

Whilst going round the cover he heard more shots and then some shouting which seemed to be coming from The Nooks. He went through the Cover and saw about six or seven men, at least one armed with a gun, facing the police who had now come up from behind the shelter. More men were joining from the Cover – about fifteen – and he climbed the hedge and ran up with the last of the men. As he reached the back of the group one of them turned round and looked at him. ‘Hello, Gippy, are you here, then,’ he said. As soon as Gippy turned away from him, a man turned round and pointed his gun at him. He said ‘No, no, Shifty, none of that’ and Shifty turned round as the rest of the men started throwing stones at the police.

Crisp shouted to him to join them, and he ran through the line of men towards the police who were still being stoned. The poachers kept up the hail of stones and drove him and the police back towards the lane. He was hit by numerous stones and just as they got to the lane one hit him on the back of the head knocking him over. He heard someone shout, ‘Let’s give that old devil a good seeing to’ and he shouted at the police not to leave him behind.

The poachers obviously decided to leave him alone and the police came back to help him to his feet. He couldn’t walk very well without help and Crisp took him to his home near the Plum Pudding and stayed the night with him and sent to Rugeley for a doctor. Mr. Benjamin Miller, a surgeon, dressed the wounds on his head – one was an inch and three quarters in length and half an inch deep and he had numerous bruises on his back.

Despite feeling weak and nauseous he went to Rugeley to see Dr. Hammond, the magistrate, and supplied the details of the night poaching and assault together with the names of seven men he could positively identify. After that he spoke with Crisp and Inspector Turrall and they suggested that he kept the names to himself until the police could gather sufficient forces together to make the arrests. They wanted to make sure that none could get away, so they were calling in police officers from all the surrounding villages as well as Rugeley and possibly even from Stafford. Outside his house the next day by the canal tunnel he talked to Thomas Warren, a local farmer, and when asked about the poaching he said that he didn’t recognise any of the gang because of the clouds obscuring the moon.

Gifford Weate was woken up before dawn on 16th November by thunderous knocking on the door and shouts to open up for the police. He looked out of the window and saw two policeman and looked out the front and saw another two. There was no point trying to run – at least five of them – so he asked his sister to vouch for him again and then opened the door to them. He was given a scant few minutes to get dressed and then was led away. When he got outside, he saw about twenty-five to thirty police together with six other prisoners (Ike Conway, Gippy Greatrix, Tommy Hiden, Abe Key, Shifty Marklew, and Jack Whitfield) – the police had obviously started in Handsacre and worked their way through the village.

They were marched off to Rugeley where they appeared before the Hon. R. Curzon and W. Harwood Esq. M.D. on a charge of night poaching and violently assaulting Inspector Turrall. Their solicitor, Mr. Passman, wanted to call witnesses who would prove that they were elsewhere, but he was refused, and they were committed for trial at the next assizes. Mr. Passman, asked for bail but that too was refused, and they were sent to Stafford Gaol.

A couple of weeks later, on 28th November, they were back in court, in Stafford, before two more magistrates – Major Chetwynd and Edward Knight Esq. M.D. This time they were charged with assaulting James Hampton. They were defended by Mr. Passman who again applied for bail, but it was refused. They had discussed the potential penalties and instead of just imprisonment they had been told that, because they had been caught night poaching in a gang, they could face transportation, but they had difficulty believing that would happen. For the married men, in particular, even a seven-year transportation sentence would be devastating. When Gifford Weate had a chance to talk to Hampton in the Magistrates Court, he said that if he thought he would get transported he would give him another blow or two right there and then.

On 23rd March 1851 the seven prisoners were brought before Mr Baron Platt at the Crown Court in Stafford on the charge of ‘feloniously cutting and wounding James Hampton with the intent to do grievous bodily harm’ and a jury was duly sworn in. The men were defended by Mr. Kettle assisted by Mr. Macnamara whilst the prosecution was led by Mr. Huddleston and Mr. Richards.

Their names were declared as

- Isaac (Ike) Conway

- James (Gippy) Greatrix

- Thomas (Tommy) Hiden

- Abraham (Abe) Key

- Thomas (Shifty) Marklew alias Bellison

- Gifford Weate

- John (Jack) Whitfield

Mr. Huddleston related the main facts and then Mr. Richards called James Hampton to the stand. Hampton told the court what had happened on the night in question and then about the events in the days after the attack. He was interrupted by Mr. Huddleston who said that he had just been informed that persons were going in and out of the Court conveying information to the witnesses for the defence. Judge Platt called Inspector Turrall who stated that he had seen a woman and Mr. Passman’s clerk talking to the witnesses. The clerk was immediately sworn in and acknowledged that he had been out of the Court and had called one of the witnesses out of the waiting room, but it had merely been to find out whether anyone had spoken to the police officers. Whilst his explanation was accepted, the Judge stated that no-one else connected with the case should leave the Court.

Under cross-examination by Mr. Kettle, Hampton stated that he had met Mr. Warren and he might have said that he did not know any of the men who were out that night but he had agreed not to mention the names. It was believed that some of the men would have run away if they knew they had been identified. He wanted them kept in gaol rather than being given bail because he feared what they might do to him.

Sub-Inspector Crisp was the next witness. He expanded on Hampton’s testimony and stated that seven men came out of Garlands Hay Cover with Abraham Key in the middle pointing a gun at the police officers. He saw the defendant Conway with a bludgeon resting on his arm. He saw Whitfield throw a stone at him which hit him on the chest. Feaveryear was also hit with a stone. He saw Weate with a bludgeon and a gun standing behind Feaveryear. Weate threw the bludgeon at Feaveryear who was knocked down on his hands and knees. He also saw Marklew and Hiden but did not see them do anything. Under cross-examination he said that he had lived near the defendants for three years and he was quite certain that they were part of the gang who had assaulted them.

Inspector Turrall and Officer Feaveryear also corroborated the first two witnesses. Each of the witnesses had been given copies of their depositions and Turrall had received a copy of all the depositions.

After a brief statement from the doctor who had treated Hampton’s wounds the case for the prosecution was completed. Mr. Kettle then argued that there was no evidence to show intent to wound Hampton individually and that it was necessary to prove that intent for a case of this kind to be substantiated. Judge Platt disagreed.

Mr. Kettle then addressed the jury. He claimed that cases of this kind should have been settled in the lower courts and complained that the defendants’ witnesses had not been heard at the previous hearings – if they had been heard his clients would have certainly been freed at that time. He complained bitterly that his clients had been denied bail and had to spend months in gaol when they were innocent. He stated that conditions on the night in question were such that identification of the defendants was impossible and he would now call witnesses who would provide an alibi on behalf of three of the defendants and if he did that to their satisfaction, he had no doubt that they would acquit the other defendants as well.

John Whitfield’s alibi: Robert Millett, a blacksmith who now lived at Blithbury, and father-in-law of Whitfield, testified that he went to his son-in-law’s house to look after his three grandchildren aged 4,3 and 2 whilst his daughter went to Rugeley. His daughter, Sarah, belonged to the Parish clothing fund, and she had taken her voucher to Parkes’ shop to get clothing for the children. She returned at about six o’clock with Whitfield. Millett spent the night at the house, going to bed between eight and nine o’clock, where he slept in the same bed as Whitfield who did not get up in the night until five o’clock. The door to the bedroom opens with a very great noise and Whitfield could not have opened it without Millett hearing it. On cross-examination he stated that he heard the clock strike all the hours of the night. Walter Moore was next called as a witness and he testified that he saw Millett at Whitfield’s house on the night in question. Both witnesses had attended the two previous trials but had not been called.

Abraham Key’s alibi: Abraham Conway, a blacksmith, stated that he knew John Key, the defendant’s father, and had been in the habit of sleeping in the same bed as the defendant. On the 6th November they went to bed at about half past nine. He got up at half past six the next morning and left the defendant, Key, in bed. The defendant’s parents and two sisters live in the house and he and the defendant had to go through two bedrooms to get to their own. It was very dark when they went to bed and he slept very soundly but did not think that Key could have got out of bed without his knowledge. He had also attended both previous trials but had not been called. (Abraham Conway married Abraham Key’s sister just three weeks later).

Gifford Weate’s alibi: Rosannah Weate, sister to the defendant, stated that she lived in the same house with her father and brother. The defendant slept with her father and had to go through her room to get to his. He had gone to bed at about eleven o’clock. She got up at about seven o’clock and the defendant came downstairs at about eight o’clock. He had not been out all night. Under cross-examination she acknowledged that she had been a witness for her brother before when he had been charged with shooting a hare at four o’clock in the morning. She stated that she had woken up several times but did not go into his room to see if he was there.

John Whitfield was given a good character reference by Reuben Dawson, brickmaker, John Jackson, butcher, and Thomas Willetts, shoemaker.

Isaac Conway was given a good character reference by Thomas Warren, farmer, and Samuel Painter, carpenter.

Mr. Huddleston then replied and stated that the alibis were all false and the case had been proven. The Judge summed up the evidence for the jury, commenting on various aspects. He condemned the police use of obtaining copies of their depositions and observed that they might have found the procedure convenient but often learned their statements by rote as a child might learn its lesson.

The jury returned a verdict of common assault against all the prisoners.

There was a second indictment against the defendants, ‘for entering enclosed lands on the night of 6th November, at the Parish of Mavesyn Ridware, being then and there armed with guns or other offensive weapons, for the purpose of taking and destroying game’. However, no evidence was offered on the part of the prosecution.

In passing sentence the Judge stated ‘It now becomes the duty of the Court to pronounce the sentence of the law, for a most atrocious and cowardly, a most unmanly assault, committed by sixteen men on four. It seems that you are part of a lawless gang, and these gangs must be put down by force of law’. He went on to outline crimes that some of the men had been arrested for before including those that they had escaped from i.e. were found not guilty. In the Judges opinion, though, all these crimes were nothing in comparison to the offence of ‘bringing before the Court witnesses to prove an alibi and those who have committed this gross offence shall be punished more severely than the others’.

Conway, Greatrix and Marklew were sentenced to eighteen months whilst Key, Weate and Whitfield were sentenced to two years with the addition of hard labour.

Just over 12 months later, on 30th March 1851 the census records five of the seven men were still in Stafford Gaol. Abraham Key, aged just 23, had died in gaol on 28th January 1851 and was buried in Armitage. For some reason Jack Whitfield had been released much earlier than the rest and was living in Handsacre with his wife and children. A few years later they moved to Walsall.

Isaac Conway returned to Handsacre and eventually married and had ten children – he lived until the age of 91.

James Greatrix was already married in 1849 and he had another six children making thirteen in total. He lived in Old Road in Armitage and worked as a labourer at the pottery. He died in 1892, aged 75.

Thomas Hiden was also married by 1849 to Rebecca Larkin from Leek. She moved back to Leek with her young son to stay with her parents whilst he was in prison. On release he joined her there and then, in 1869, they emigrated to USA.

Thomas Marklew had been married for about 12 years when he was sentenced and on release he returned to Handsacre where he died in 1888 aged 66.

Gifford Weate returned to Armitage after finishing his two-year sentence. At least two of his brothers emigrated to Australia in the 1850s and he last appears in a record in 1857 when he is tried for poaching hares at Rugeley Petty Sessions.

Ellis Crisp was from Suffolk and joined the Staffordshire Constabulary in 1844 just two years after it had been formed. His initial rank was 3rd Class Constable but by the time of the poaching he had been promoted to 1st Class Constable. In July 1851 he was promoted to Inspector and transferred to Rugeley.

James Hampton became Josiah Spode’s gamekeeper in the mid 1840s and worked for him until his death in 1866. His son William followed in his footsteps.