Like over half of the listed buildings in the parish, Clarke Hayes on Lichfield Road, Handsacre, was listed in January 1988 following a survey in 1986 – part of a nationwide survey triggered by the demolition of the art-deco Firestone factory in Brentford, London. Whilst the property might not have looked particularly old from the outside, a 1981 sale advert stated it had ‘tremendous potential and a wealth of exposed beams and other delightful features including an inglenook fireplace’.

The name Clarke Hayes has had various spellings e.g. Clerk Heyes but does not appear to have been used before the mid 1800s. In the tithe map of the late 1830s Clark’s Piece was recorded down Bromley Lane whilst this building was not given a name at all. The name Clark/Clerk/Clarke signified a member of a religious order whilst Heyes signified an enclosure, often fenced.

The survey concluded that it was a square panel, post and truss timber-frame building that had been built in about 1630. Until the 17th C there had been an abundant supply of oak but it became more scarce so less wood was then used in construction and cruck houses were replaced by timber framed houses. These houses were essentially big boxes with upper “boxes” i.e. storeys, set on lower ones. Perimeter footing of an impervious material – ashlar stone in this case – went down first and then a sill beam laid on the footing. Upright beams were mortised into the sill beam and tenoned at the top into another horizontal member.

The timber frame would have been pre-fabricated on the ground, possibly at the carpenter’s premises, to ensure that each piece fitted with the other – every joint was unique and custom fit. In order to make sure that the correct pieces of wood were put together the carpenters scribed the wood as shown in this joint below.

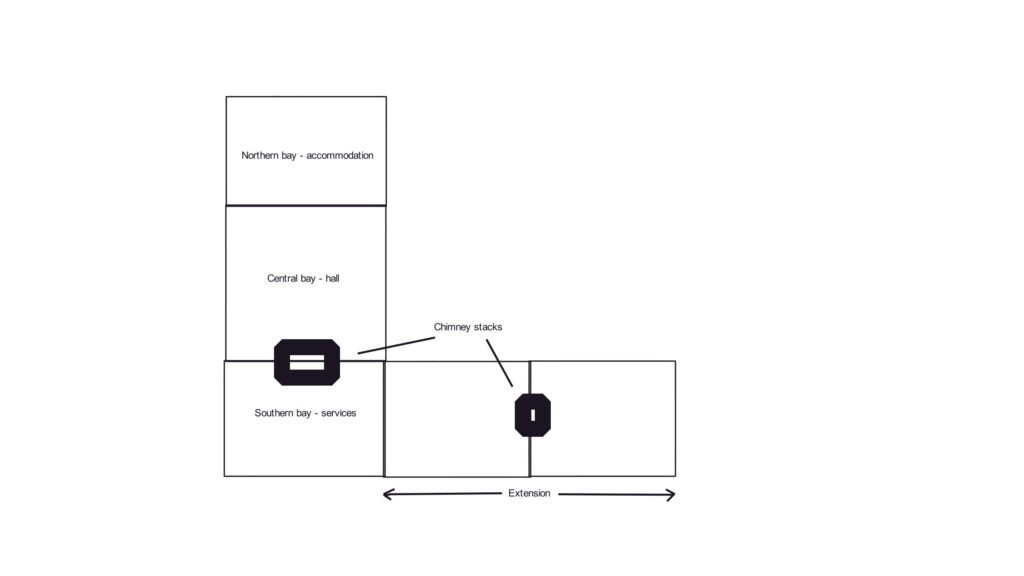

Originally it had been rectangular with three bays – north, central and south – with the central bay being slightly larger than the other two and forming the central hall. The south bay had services i.e. scullery etc whilst the north bay was for accommodation. The building stood on a sandstone ashlar plinth and had a substantial ashlar and brick chimney stack between the central and southern bays. In the northeast corner there was a small half-cellar and the upstairs still had oak plank doors with the original timber latches, bolts and cockshead strap hinges. It had ground floor, first floor and attic and had originally had a thatched roof.

About a hundred years after its original construction a brick-built wing was added on the east side of the southern bay making it into an L shape building. The extension had two bays with a chimney stack between the two bays. At this time the services would have been moved into this wing freeing up the south bay of the original building. Later in the 1700s the north end wall was rebuilt in brick and a new chimney stack added for heating up two upper rooms which had been created by splitting one room by a partition. At some point the thatch was removed and Staffordshire Blue tiles used instead.

During the 1800s a low brick lean-to was added to the rear of the north and central bay with a doorway cut through the central bay.

In the late 1800s or early 1900s the original building was partitioned to make the L shaped building into two cottages. To give a larger floor plan two 5-sided wings were added at the front of both the north and south bays. This though meant cutting away the ground floor timber framing which created considerable structural stress. A similar problematic addition was made on the southern wall. The whole building was given a stucco rendering in the 1930s.

As can be seen from the photographs below, by the time it was bought by Graham Shaw in the late 1980s it was in a sorry state. The first main structural issue that needed tackling was that the north end was no longer watertight, thought to have been the result of a lightning strike. A second issue revolved around the stucco application – in order to get the stucco to adhere it had been necessary to hammer nails into the oak.

The end result was that many of the lower oak timbers had rotted together with the base beams and the stone plinth had been damaged and all needed careful replacement. The five sided extensions were removed as was the lean to extension against the east wall. Both the stone work and the timber required skilled craftsmen just as it did 400 years ago. Newly felled oak can be used in construction but it can warp and twist as it dries so to speed up the process it is soaked in water for a few weeks – in previous eras it was simply thrown in the river for a while. This process and the skills needed for this type of renovation make for a lengthy and expensive operation.

During the renovation it was discovered that the original building had been thatched but the inspector from the authorities wanted the Staffordshire Blue tiles retained as they too were important from the building history perspective.

The following two photographs show the ashlar/brick chimney breast and the timber structure.

All the old buildings in the village needed water and most, like Clarke Hayes, had their own well. A previous owner had simply capped off the well with concrete and cast iron and inspection revealed a 30 ft deep well with a side passage which probably had supplied the half-cellar. The well was also restored as can be seen below.

The building was deemed within the safeguarded area for HS2 and was therefore sold to them a few years ago. Apart from some vandalism the property is still stunning as can be seen from the photograph below. Many thanks to Graham Shaw, not only for the use of his photographs and provision of information, but for all the time and effort he put in renovating this wonderful old building.