The Boer War (11th October – 31st May 1902) was fought against two Boer Republics – the Republic of Transvaal and Orange Free State – and was the culmination of more than a century of conflict. The trigger for the war though was the discovery of diamonds and gold in the two states. When war broke out the well-armed Boer irregulars immediately struck and invaded the Cape Colony and the Colony of Natal, besieging the British garrisons at Ladysmith, Mafeking (with its important railway junction), and the diamond mining town of Kimberley.

Taken by surprise the British Government scrambled to put together a new force and troops were immediately sent from Britain, the Mediterranean and India. The newly arrived troops were split into three columns and set off to relieve the besieged towns, but each was defeated in a single week at the Battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. This became known as Black Week and led to a big change in Government thinking and the appointment of a new commander – Lord Roberts.

William Henry Ottey was born in Handsacre in 1876 where his father, Levi, had several general labouring jobs including working as a platelayer on the railway. By 1896 they had moved to Old Road, Armitage and William was also working as a labourer – for Mr Brassington in Rugeley. William joined the 2nd Battalion of the North Staffs in 1896 after a spell in the Militia and was thus a serving soldier when war broke out. From October 1899 to March 1900 over 1,000 men per day sailed to South Africa from different UK ports and William left with the 2nd Battalion from Southampton on 15th January 1900 on the RMS Aurania. The ship also carried contingents from the Royal Engineers, 2nd Berkshires and some of the Manchester Regiment, totalling over 1500 men. After a passage of 19 days, they arrived at Cape Town on Saturday 3rd February and were immediately reorganised and sent into battle.

A few weeks earlier Lord Roberts had arrived to take command of British forces in South Africa and had decided on his plan of attack. He intended to drive into the Orange Free State, capture the capital, Bloemfontein, then drive on to Pretoria. This though would ignore Kimberley which was under siege so a cavalry force would be despatched to Kimberley. He drew in troops from all across Cape Colony, but he only had one brigade of cavalry which would not be enough to relieve Kimberley. His solution was to order every infantry battalion in South Africa to raise a company of mounted infantry. These companies were detached from their parent battalions and operated as eight independent Mounted Infantry battalions giving him an extra cavalry brigade. As soon as William arrived in South Africa therefore he was detached from his battalion, joined the 8th Battalion Mounted Infantry and, within a week, was on his way to relieve Kimberley.

The cavalry, under General Sir John French, started out on the 11th February and headed East with his route across two rivers, the Riet and the Modder. Following the Riet for twenty miles then crossing it and a further twenty-five-mile trek across the dry veld allowed him to deceive the blocking Boer force and he crossed the Modder without serious opposition. From this point however the Boers held the hills in a semi-circle around a shallow valley with only a pass at the head of the valley. French decided however to take a risk and sent his whole force for the pass and after a five-mile gallop along the valley the whole 5,000-man force broke through the pass with only one killed and twenty wounded. The road to Kimberley was now open before him and by 6.30pm on 15th February they were in Kimberley and the Boer forces outside the town abandoned their lines and retreated.

I wish my mother could see me now, with a fence-post under my arm, And a knife and a spoon in my putties that I found on a Boer farm, Atop of a sore-back Argentine, with a thirst you couldn't buy, I used to be in the Staffordshires once, (Sussex, Lincoln's and Rifles once), This is what we are known as - we are the men that have been Over a year at the business, smelt it an' felt it an' seen We 'ave got 'old of the needful - you will be told by and by; Wait till you've heard the Ikonas, spoke to the old M.I.!

There are many stanzas for Rudyard Kipling’s poem (above) and in this one he uses the slang word Ikonas for the Mounted Infantry personnel which suggests that they weren’t above appropriating provisions or remounts wherever they could find them. Quite often the Mounted Infantry were short of provisions as convoys of supplies often failed to keep pace with them. It also reinforces the point that they retained their individual regimental identity and even their own uniforms. After the rush into action at Kimberley the remainder of William’s time in the war was varied and arduous. At times it would be in pursuit of the Boers with ambushes and short vicious exchanges of rifle fire. But it also involved in clearing cattle, burning farms and taking away any remaining stock – the scorched earth policy.

William was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal with Johannesburg, Cape Colony and Relief of Kimberley clasps and the King’s South Africa Medal with 1901 and 1902 clasps.

Whilst William was in South Africa his cousin, Thomas William Ottey, had two children baptised at Armitage – William Charles in 1900 and Thomas Victor in 1901. Thomas had been born in Handsacre but had left over twenty years previously and had no apparent reason to bring his sons for baptism apart from the presence of his Uncle Levi and family – maybe it was as some sort of comfort to the family whilst William was away. At the time Thomas was a Warrant Officer in the Army Ordnance Corps and went on to become a Major, dying in 1918.

A Special Army Order was issued on 20th December 1899 recalling reservists and Arthur William Dawkins was the only Armitage man to be recalled. He was Armitage born and bred and, like his father, Morris, before him he had worked as a miner but in 1892 he had joined the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards, otherwise known as the Grenadier Guards. After three year’s service, all spent in the UK, he had been transferred to the Army Reserve on 19th February 1895 and returned to the village and the pit. He had now been recalled to the colours – just days before Christmas. On Thursday 4th January 1900 he was treated to his own reception at the Swan with over 50 people sitting down to a meal and an evening of song from all the village soloists like Elijah Mould and Bill Flackett. As a parting gift they presented him with a handsome pipe in a case and a quantity of tobacco. He joined the rest of the 2nd Battalion and sailed on board the Dunera arriving at the Cape on about 11th April. They formed part of the 16th Brigade under Major General Barrington Campbell and part of the 8th Division under General Leslie Rundle. They immediately entered the field at Orlogspoort and Dewetsdorp and the Boers retreated without any severe fighting thus relieving Wepener. This became a theme throughout their time in South Africa with lots of small actions but no great battle. During the two years and one month they served, some part of the 8th Division was almost daily engaged. Some of the battalions in the Division would be on garrison duty whilst others were out trekking with columns to strip the country of supplies, taking convoys to garrisons and the mounted columns or capturing commandos. Most of their time was spent in the Orange Free State which had lots of mountains and fertile valleys and was a stronghold for the Boers. They were mainly employed in the Brandwater Basin or about Bethlehem or Harrismith. A typical action fought by the Grenadiers was fighting off a strong force who held hills commanding the road with the Boers putting up a stiff resistance.

Arthur was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal with Witteberger, Cape Colony and Transvaal clasps and the King’s South Africa Medal with 1901 and 1902 clasps.

Recalling reservists was not enough so a Royal Warrant was issued on 24th December 1899 creating the Imperial Yeomanry. The County Yeomanry forces were not intended to serve overseas so the Royal Warrant asked County Yeomanry Regiments to provide service companies, for the Imperial Yeomanry, of about 115 men each who would serve as mounted infantry – essentially replacing the sword with rifle and bayonet.

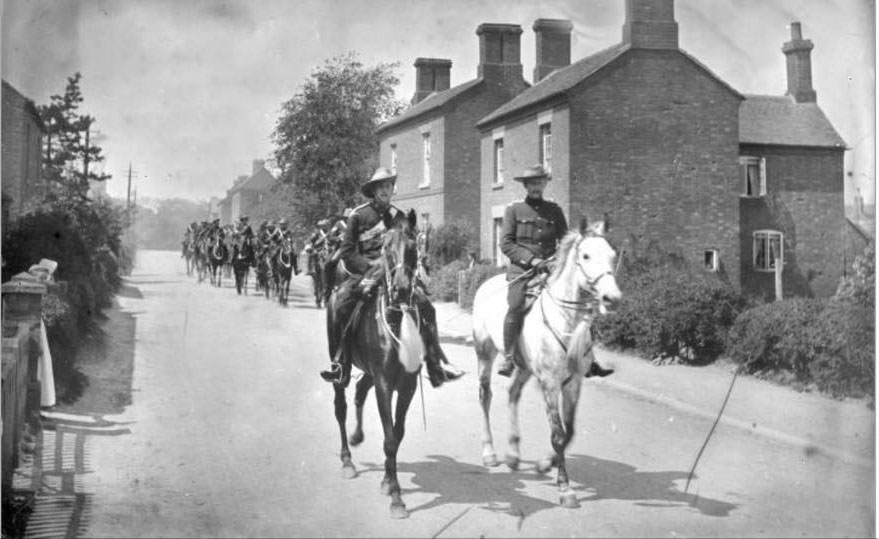

Herbert Cecil Gardner was a Lieutenant in the Staffordshire Yeomanry and he volunteered for South Africa and became a Lieutenant in the 6th (Staffordshire) Company of the 4th Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry. This picture is believed to show the Imperial Yeomanry on their way down the New Road to Armitage station prior to setting off for South Africa. The government supplied their arms, ammunition and kit and would pay for their transport but each individual had to pay for their own horses and saddles. This cost about £170 or £13,000 at modern prices. Apart from saving on costs the theory was that it would attract a better class of trooper – educated, moral and patriotic.

The Company gave a good account of itself in action at the Battle of Constantia Farm (Thabanchu) and Senekal (Biddulphsberg). Neither ranked as one of the big events of the war but the actions and bravery of the troops were just as important. A war correspondent A.G.Hales gives a very detailed description of the action in his book ‘Campaign Pictures of the war in South Africa(1899-1902): Letters from the front’. His eyewitness account states that They were the Yeomanry and mounted infantry, and numbered about 600. A more workmanlike body of fellows it would be hard to find anywhere. They sat their horses with easy confidence, and looked full of fight. Some of them carried their rifles in their hands, muzzle upwards, the butt resting on the right thigh; others had their guns slung across their shoulders. Group after group went eastward, and the Boers knew nothing of the movement, because we were for once employing their own tactics. (You can see on the picture below when they are coming back up the New Road from Armitage station exactly what he means about the different way men held their rifles).

His opinion of them of them was: The Yeomanry did a lot of useful work, and are as eager for fight as a bull ant on a hot plate. They are as good as any men I have seen in Africa, full of ginger, good horsemen, wear-and-tear, cut-and-come-again sort of men. They adapt themselves to circumstances readily, are jolly and good-humoured under trying circumstances. Their officers are, as a rule, first-class soldiers, equal to any emergency.

By the end of March 1901 almost 30% of the original ten thousand or so Imperial Yeomanry had been killed, injured, or taken prisoner though the majority of the losses were through disease. The survivors were slowly demobilised as they could return home after twelve months. The Staffordshire Yeomanry provided the 106th (Staffordshire) Company for the 4th Battalion in 1901 and Lt. Gardner returned home to a hero’s welcome. He arrived at Armitage station on Monday 10th June 1901 having been away for sixteen months in total. According to the Lichfield Mercury, flags and bunting was on display in profusion and archways with banners were erected on the whole route from the station to his home at the Tower. A welcoming committee had been formed and all the children in the village entertained and fed. He was carried shoulder high to his carriage and then the horses removed from the traces and the carriage was drawn through the village by the men. An illuminated address in a golden frame was presented to him – paid for by the parishioners.

The war for Herbert Dawkins (younger brother of Arthur above) could not have started any worse because he was arrested for desertion at his home in Armitage in February 1900. According to the newspaper report he belonged to the 4th North Stafford Militia, stationed at Newry, Ireland. He had neglected to go for his annual training but claimed that he had never received a notice. (If he had in fact deserted you would have thought he would not have been found at home). He was remanded for escort back to his regiment and on March 4th he was on board SS Nineveh bound for South Africa to serve in the 4th Battalion.

They were initially deployed in the Cape Colony. In Herbert Gardner’s response to his presentation (above), he said “Armitage ought to be proud of the men they had sent out. The men who were guarding the lines of communication he thought were doing more work than those who were actually fighting”. He might well have been talking about Herbert because that is what he was doing, first in the Cape Colony and later he was part of a small imperial garrison at one of the vital points on the railway in Bechuanaland Protectorate.

At the age of 32 he was recalled to the colours at the start of World War 1 and his attestation form states that he had been discharged from the 4th Bn for being medically unfit although no specific reason is given. He was discharged again after less than three months – ‘not being likely to become an efficient solder’.

James Edward Wagg’s route to South Africa was via Somerset and the Punjab but he eventually arrived in the Transvaal in March 1902. His father had moved to Armitage in the 1850s when Penman opened the New Pottery and had followed him to Glasgow before returning to Armitage where James was born in 1875. The family were all in the pottery trade which is perhaps why James decided to become an apprentice to a Master Carpenter who had worked in the village, possibly on the Club & Institute, and moved on to Somerset with him. That didn’t work out though and after a brief spell as a groom he joined the 4th Bn Somerset Light Infantry Militia before being posted to the 1st Bn. Dorset Regiment in 1893.

After a couple of years in the UK the battalion was posted to India where they served in Southern India with all its heat and humidity. In 1897 though they were despatched to the North West Frontier Province as part of the Tirah Expedition – a quite different climate and rugged mountainous terrain. The Afridi tribe had received a subsidy from the government of British India for the safeguarding of the Khyber Pass in Tirah for sixteen years before they rebelled and captured all the posts in the Khyber and the pass itself in August 1897. Several other rebellions took place at the same time and it was October before forces were put together to quell the revolt and in such a mountainous area it became bitterly cold, down to -21°C. The narrow passes were often defended stubbornly by tribesmen and progress was slow.

As part of the campaign there were two separate battles to control the Dargai heights in October. The Dorsets, along with the 2nd Gurkhas were involved in the second attempt on the 20th. The worst aspect of the climb was an open space that had to be crossed. This was a killing ground for the sharp-shooting tribesmen some 200 yards above them. At 10am the Dorsets gave covering fire as the Gurkhas dashed across, sustaining 71 casualties in just ten minutes.

It was now time for the Dorsets who were not used to this type of terrain and had seen little action up to this point. Companies A – D had been giving covering fire for the Gurkhas so E Company went first but the Captain was hit and most of the leading section went down. A few got across with some reaching the half-way rocks. F and G companies fared little better. One Company of the Sherwood Foresters attempted to go across with G Company but this proved too difficult due to the crowded conditions below the ledge and the number of wounded who were being treated. Eventually the Gordon Highlanders moved forward, and the heights were taken. It had cost the Dorsets nine dead and many more wounded.

During the rest of the winter months, the fighting was just as bitter but as the weather improved the British forces slowly began to overwhelm the Afridis and, finally, in June 1898 the fighting was over.

The 1st Battalion remained in India but towards the end of James’ tour of duty, in March 1902, he joined the 2nd Battalion in South Africa. They did a lot of heavy marching as the infantry of a column under Brigadier General Bullock which operated chiefly in the south-east of the Transvaal. In September 1902 he left South Africa and came back to the UK where he was transferred to the Reserves.

He was awarded the Indian Frontier Medal with Punjab and Tirah clasps, the South Africa 1899-02 medal with Transvaal clasp and the 1902 clasp.

John Talbot, a miner, and his wife, Mercy, were both born in Woodseaves, Staffordshire and moved around Stafordshire before settling in Amington where Mercy became a midwife. For about five years, between 1877 and 1882, they lived in Handsacre where they had four children including David and William. Other than a very brief newspaper clipping stating that William Talbot was at the front in the Boer War I can find no other records about him. For Lance Corporal David Talbot of the 2nd Bn North Staffs there is not much more in the way of records. In June 1900 he left the barracks and was almost immediately in hospital with enteric fever. On 15th December he died at Deelfontein Hospital, (a tented general hospital), after a third bout of enteric fever.

In the evening of 12th December 1902, six months after the end of the war, Armitage had an evening of celebration. The school children sang a cantata about Father Time then various adult soloists added another dozen or so songs, including Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Tommy Atkins’ with the chorus –

Tommy, Tommy Atkins, You're a "good un", heart and hand; You're a credit to your calling, And to all your native land; May your luck be never failing, May your love be ever true! God bless you, Tommy Atkins, Here's your Country's love to you!

At the conclusion of the entertainment Arthur Dawkins, Herbert Dawkins and William Henry Ottey were each presented with a marble clock, accompanied with a framed testimonial with the following transcription: “Presented to …………. on his return from active service in South Africa, as an acknowledgement from the parishioners of Armitage for good work done with his regiment during a long and arduous campaign”. It was signed by H.W.Gardner, Chairman of Committee.

The newspaper clipping states that Private Richard Dawkin had already received his testimonial, but I cannot find any reference in any records e.g. census, baptism for either Dawkin or Dawkins.